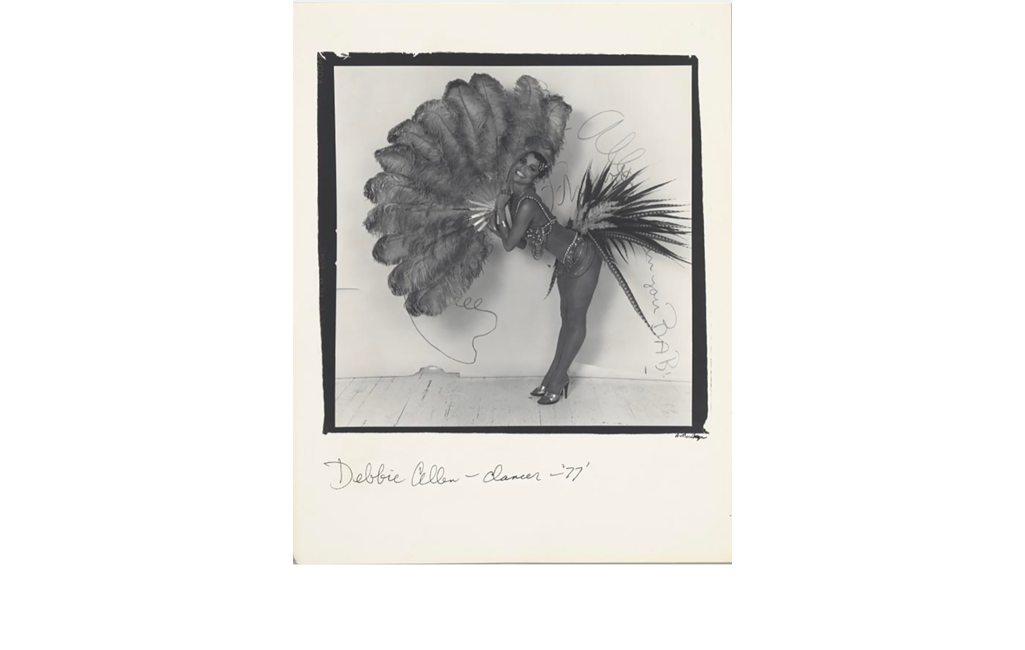

On The Collection: Debbie Allen – dancer

Jessica Lynne

In approximately 1,000 words, we invite you to confront a work of visual media (film, photograph, painting, or object) in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture (1950 – present) and reflect upon a public or private future that the maker(s) of that piece envision, have envisioned, or a future that might be imagined through your engagement with the piece.

The first time I saw Debbie Allen dance, I was sitting in the living room of my late Aunt’s home, outside of Richmond, Virginia, watching Fame. Allen played the role of Lydia Grant, the iconic dance instructor at the New York City High School for the Performing Arts. My aunt had the series box set, and I—her awed eleven-year-old niece—was hooked. I can’t recall why we binge-watched the show, but it remains a singular afternoon in my childhood memory. With each episode, Lydia Grant doled out new wisdom and a seemingly impossible choreographic routine unlike any I had ever seen. Who’s that, I asked my aunt. Debbie Allen, she replied, she’s a legend. It was non-negotiable: Debbie Allen, a legend.

I conjured this exchange with my aunt when I encountered Anthony Barboza’s 1977 black-and-white portrait of Allen. The acclaimed dancer/choreographer bends at the waist while holding a large feathered fan. She is wearing a beaded bikini and headpiece, complete with tailfeathers and high heels. Her hair is slicked down in large finger waves. Her smile is radiant as she poses for Barboza in front of large white backdrop. Words are written on the backdrop, though Allen’s body largely obscures them from view. The spirit of Josephine Baker looms. Allen’s pose and costume harkens back to Baker’s grand legacy of dance and fashion as one of the most significant Black performers of the first half of the twentieth century. Baker’s death precedes the image by a mere two years—a reference, I imagine, full of weight for Allen, who is not yet thirty years old. Looking at the photograph causes me to smile almost as widely as Allen.

This is what I have come to realize about Barboza’s images. You cannot just pass them by. They beckon to you. Like Allen, like Baker before her, they radiate.

As a member of the Kamoinge Workshop, Barboza was among a cadre of Black American photographers who intervened in the medium by imaging Black people ceaselessly and creatively. Founded in 1963 in Harlem, the Kamoinge Workshop established itself as the antithesis to a photography ecosystem that was largely white and male and which made little room for the exhibiting of images by photographers who were not. While the mainstream largely ignored Black photographers or trafficked in narrative tropes about Black people, Kamoinge members— including artists such as founder Louis Draper, Ming Smith, Adger W. Cowans, and Roy DeCarava—wanted to ensure that a complexity and beauty of storytelling surrounded the representation of Black life. This meant imaging Black folks in their own communities—in the U.S. and at times abroad—resisting the sensational, and insisting that the resulting photographs exist within the framework of the emerging field of fine art photography. They created narratives about the “beauty of everyday Blackness,” as Ashawnta Jackson tells us in her 2018 essay on the collective.{1} Moreover, the collective became a vital space for mentorship, critique, and exhibition-making in the wake of the US civil rights movement and subsequent Black radical movements. Barboza undoubtedly, like many of his comrades, understood deeply the enduring impact of these practices.

Photographs by Anthony Barboza, 1965 – 1977.

Barboza’s portrait of Allen is part of a series of artists portraits, made throughout the 1970s, entitled Black Borders (though it should be noted that he did not exclusively work as a portraitist) that includes Amiri Baraka, James Baldwin, and Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela. Through them, we trace diasporic lineages, grounded in myriad forms of cultural production. What remains enchanting to me about this gesture of posterity is not just its technical mastery but the way it envisions a future. I love the way a single photograph becomes a record of time’s magnanimity. It’s almost as if Barboza knew that we would be here, learning from them still. Not just their words or compositions, but from their smiles, their joy.

At its best, portraiture is an intimate process, an act of care. And here is Allen, not yet in her prime, a few short years after graduating from Howard University, having just landed a role on the short-lived NBC show 3 Girls 3, all while slowly becoming part of the canon of Black Dance herself. Baker, Katherine Dunham, Carmen De Lavallade. The list could go on. Barboza sees this, and Allen, smiling, is sure of what awaits her.

{1} Ashawnta Jackson, “When the white establishment ignored these black photographers, the Kamoinge collective was born,” Timeline. March 14, 2018.