His films are fixtures at the Sundance Film Festival, on public television, and more recently, accompanying permanent installations at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. Over the course of more than three decades, Stanley Nelson has demonstrated a singular commitment to using the documentary mode to challenge dominant discourses that tend to shape American historical memory. His films have chronicled twentieth-century African American social movements and historical figures, both prominent and underexplored. This conversation with Nelson occurred at his Firelight Media offices in Harlem, NY, where he has at least three new projects in various stages of production. The offices also play home to the Firelight Media Producers Lab, a significant incubator for emerging documentary filmmakers of color. In our conversation, I asked the filmmaker if we could step back from discussions of the choices that comprise particular films and instead engage with the social, political, and commercial registers in which his films are always entangled.

****

Interview

Jason Fox

I want to start with a broad question about your outlook on your own practice. In your Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015), you interview a journalist who says “the Black Panthers used us.” He was referring to the savviness of the Panthers in understanding how to make use of the commercial media at large. That was a really poignant line for me, and it makes me wonder how you would relate it to your own work. On the one hand, I see you making boundary pushing work, getting engaged discussions about the Black Panthers, for example, into spaces where those discussions usually don’t happen. On the other hand, you have made a career partnering with public institutions like PBS and the Smithsonian Museum that aren’t immediately associated with pushing boundaries. How do you think about your own films in relationship to the channels through which you distribute them?

Stanley Nelson

I tend to think that all outlets are pretty much the same. I wouldn’t say that Netflix is any more revolutionary than PBS. I think almost all outlets with a wide reach, at this point at least, are owned by corporations with money. Netflix started out little, now they’re huge! So, I think of my approach less in terms of where it’s going to be broadcast, and more about audience and trying to reach as many people as I possibly can. In the case of Black Panthers, I could’ve made a film about my relationship to the Black Panthers. I was 15 or 16 when the Panthers came into being. I lived in New York City. I was their target audience. I could talk about that, I could talk about me and my best friend—we went to the Panther headquarters in Harlem, stood across the street and said, “Uhhhhh, no! I don’t think so. I don’t think this is what we want to do.” I could’ve made that film, but I think it’s much more important, to me, to make a film that’s not about me, and not about my personal stories.

JF

Can you say more about intended audience? In the context of your Tell Them We Are Rising (2017) about historically Black colleges and universities, for example, those who attended HBCUs are the last people who might need or want to see the film because they’re thinking “yeah, we already know!”

SN

That’s always the trick with that convention. Especially historical documentaries that I’ve done. There are people who see HBCUs and know a lot about HBCUs. There are people who see HBCUs and they’re like, “Whatttt? Oh my god!” Especially internationally. We showed the film in France and they were like “What? There are Black colleges? I didn’t know anything about that!” You have this variation of people. One thing I’ve said before, I’m not sure how true it is, but in some ways I’m looking to tell Black people something new. I’m looking to tell African Americans something they don’t know. I feel if I can tell African Americans something they don’t know, by its very nature I’ll tell white folks and

people in other countries something they don’t know. I’m trying not to be that guy in the Tarzan movie, you know, drums are beating, and Tarzan says, “What are the drums saying?” And they say the drums are saying the Black folks are mad up in Harlem and they’re going to form an organization called the Black Panthers. I’m not trying to do that, I’m trying to make a film that tells Black people something new.

from TELL THEM WE ARE RISING: THE STORY OF HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES (Nelson, USA, 2017).

JF

I imagine that for you, your reuse of archival photographs in new contexts different from the ones in which they originated means having to navigate how they will be reinterpreted in contemporary contexts by new audiences. For example, Black Panthers uses a still photograph of Huey Newton from 1967, one in which he’s been handcuffed to a hospital gurney after being shot by Oakland police officers. So, he’s been shot, then taken to the hospital by a friend where he is arrested, and then someone photographs him while he’s lying down on the gurney. At an immediate level, it’s an image that depicts real subjection, someone without control over their body. Do you worry as a director about re-contextualizing an image like that into one of agency, or at least into an image that can circulate with a different understanding of what’s going on there?

figure 1. Huey P. Newton, a co-founder of the Black Panther Party, handcuffed to a hospital gurney. From BLACK PANTHERS: VANGUARD OF THE REVOLUTION (Nelson, USA, 2015).

figure 1. Huey P. Newton, a co-founder of the Black Panther Party, handcuffed to a hospital gurney. From BLACK PANTHERS: VANGUARD OF THE REVOLUTION (Nelson, USA, 2015).

SN

I’m not sure if those questions are in the front of my mind. I’m trying to tell a story. In the Black Panther film in particular, I grew up with the Panthers. The history that came down today about the Black Panthers is very different from what I remember, how the Panthers were thought about and what I remember at that time. So, I wanted to make sure that

the story I remembered was the real story. When we found that it was, that was the story I wanted to tell. Somebody might look at Huey Newton handcuffed to the gurney and say, “that motherfucker”—I look at it and say, there’s a guy who looks like he’s about to die, and you handcuffed him to a gurney. Like, what do you think he’s about to—get up and run? He’s about to die. And they thought he was going to die. So that’s what we saw in the picture. Those films, and the last bunch of films we made, were made without narration. We’re not telling you what to think. We’re just showing you the picture. If you think that’s a motherfucker who deserves to be handcuffed to the gurney, you’re free to think that. We just thought the picture was very powerful.

JF

You made the powerful short video about Emmett Till that is installed in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. If I remember correctly, the video is installed on a partitioning wall just outside of the Till memorial, but also immediately adjacent to where the museum has installed a guard tower from the Angola prison. When you were making the video, did you have any sense of how it would be contextualized by the objects around it?

SN

No, it’s not like we had a schematic of the museum. They would just tell us, this is how big the screen is, whether or not there are going to be seats, and they would say that they want the video to be six minutes, or a minute and a half, or whatever. And we just had to go from there.

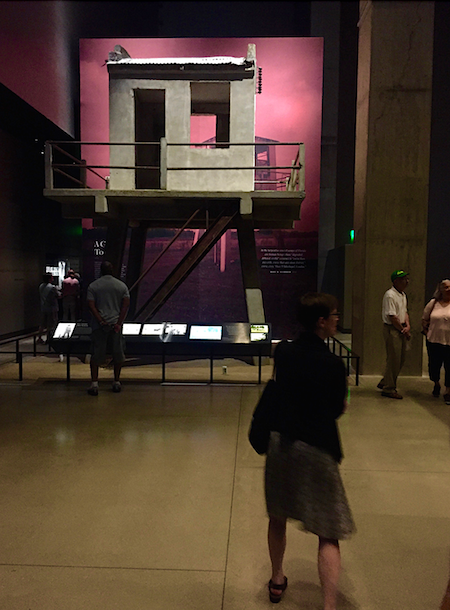

figure 2. Installation view of an Angola Prison guard tower at the Smithsonian Museum of African American

History and Culture. Behind the partition, Nelson’s video installation about the murder of Emmett Till.

figure 2. Installation view of an Angola Prison guard tower at the Smithsonian Museum of African American

History and Culture. Behind the partition, Nelson’s video installation about the murder of Emmett Till.

JF

I wonder if your relationship to how you use images surrounding Emmett Till shifted from when you first made The Murder of Emmett Till (2003) for PBS’s American Experience 15 years ago? That is, in thinking about the posthumous agency individuals or their families and cultures might want in how media renders them.

There’s a popular narrative that says the circulation of Emmett Till’s image was a catalyst for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. On the other hand, every time we see one more image of an African American child or parent murdered, the counter argument is that it reproduces the logic that this is just what happens. This is just the way things are. We don’t need to see these images. We need the events to not have happened, which is a very different thing.

SN

I think unless we know that these things happened, and the importance of them happened, then how can we say that these things can’t happen again? I think those images are really important. Somebody could make a film or write a book about that image, which has basically been kept alive by Jet Magazine, which publishes the image every year. Emmett Till was killed in 1955. I was born in 1951. I thought that I remembered his killing. But I couldn’t have. I remembered seeing that image in Jet, and the discussions it started. The editor of our film on Emmett Till was born in 1957. He too is a Black man, and he too remembered the killing of Emmett Till. I think those images are incredibly powerful and are needed. How can we say that this stuff has to stop unless we know what it is? We can’t get out of our mind, “I can’t breathe.” We can’t get that out of our mind.

These images are incredibly important in trying to force these things to be stopped. But we can go too far … An interesting story is that when we were editing Emmett Till, we became desensitized in some ways to the image of Emmett Till’s bloated and beaten body. So, we would actually invite people into the edit room, the mailman or the FedEx guy, and say, “Hey, can you spare us two minutes and watch this sequence?” We would show the sequence where he showed his body and say, “Whatcha think? Is that on too long or is it too short?” And we really used that to figure out how long to show it so it didn’t become an obnoxious moment of just rubbing this monstrous crime in your face. But you had to have an idea of what actually happened to Emmett Till, because that’s why his mother wanted to leave the coffin open. That’s why people were fainting at his funeral. It’s important that we give you that sense, without being manipulative of your emotions. Although we were, obviously.

from THE MURDER OF EMMETT TILL (Nelson, USA, 2003).

JF

When you’re scripting a project, do you start with the archival materials, and say “Ok, this is what we have … this is the history that we can tell. Now we need figures who can come in and contextualize it?” Do you do it the other way around?

SN

In the Panthers, we realized before we even started, without even thinking about it, that there was a lot of material. That the Panthers were darlings of the media. A lot of times we don’t know what the material is going to be, but we start to find more and more and more. We think about archival early, because it’s how you tell this story. We try to use every moment we’ve got. I look at archival footage and stills as a character in the film.

JF

You can correct me if my perception of the industry is wrong, but it seems like another major shift is the significant growth of the business models of media archives like Getty archives or NBC archives. History has become a lot more expensive to acquire as its aggregated and leased by fewer and fewer.

SN

Yeah, it’s more expensive. It’s harder to work deals—they’re just in it for the money. You get stuff faster, that’s the one thing, they’re efficient. But it’s getting more and more expensive. Some of these archives are buying up all the smaller archives. They understand that this stuff is evergreen. It’s like Michael Jackson’s estate buying a Beatles catalogue. How long are people going to listen to the Beatles, you know? Sooner or later, you’re going to be making lots of money.

JF

Your response sounds like a necessarily practical one. I wonder if you have a philosophical response that butts up against the practical one, like…

SN

Like “fuck you?”

(laughter)

JF

Like “fuck you,” or, what are the stakes when important cultural materials are kept behind gates?

SN

It’s rough. More and more. The answer is that people are fair use-ing material, and maybe that wouldn’t happen if people weren’t so greedy. When I’m negotiating with people I’m working with, my attitude is that you should try to get it for free. The archive is just pressing a button. They have some intern in there that’s pressing a button. We’re talking about, for The Black Panthers, we might’ve spent $300,000 on just footage. And basically, it’s them going through the archives and copying it over and sending you a link. That’s what it is, and we’re literally paying $45,000 to one source. $35,000 another source. And they’re just pressing a button. Who owns history? They own history because they have this footage. They own it because they have it. There’s been suits where they can’t prove that they own it, but they’re like, “Prove that we don’t. We have the only source, and you had to have gotten it—It has to be ours.” The last project we finished, this film called Boss, a lot of footage was off of YouTube, and it was a real headache. We had to source it. That’s the problem of YouTube, it’s all there, but … you’re making this film, you’re trying to cut stuff, but then you have to go back and figure out who owns

it. It gets very complicated.

JF

Just to get a sense of this scale, you mentioned if you’re making a film now you can spend $45,000 or $35,000 on one source; when you were making films 20 years ago, was it dramatically different?

SN

Some people I didn’t pay. Hope they’re not after me! (laughter) But you know, it’s just an escalation. Part of it is, you know, rising tides raise all boats. It’s harder for me, standing in a visible position with Firelight (Nelson’s production company) to take film and use it, so we have to source everything. But with a lot of our budgets, in our first crack at a budget for a 90-minute film we put in $270,000 just for footage. Maybe another $70,000 for stills. That’s just for stills and footage. Stills and footage that usually doesn’t belong to individuals, that usually belongs to big corporations, and all they have to do is press a button to get it to us.

JF

My understanding with the Smithsonian is that when they were commissioning videos for the museum, they largely insisted that almost all of the footage came from NBC archives.

SN

I don’t how much to get into this, it was a weird contract because it was through Smithsonian TV, and I don’t know if they knew what they got themselves in for. But they did it that way, and we were like “no,” this is going into this thing. That’s going to be the most important thing that’s ever been done that tells African American history, and so you can’t say you can’t buy this shot of Emmett Till’s funeral. You’ve got to figure it out. And I think the great thing for us was that at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, they understood that. And they backed us on that. I mean, we tried to be reasonable, but there’s only so much you can do.

At times we had to go around the Smithsonian Channel and go right to the museum, and the museum up and down supported us, from our program officer to Lonnie Bunch, who I’m sure people have told you is a genius. It’s true. He is.

JF

When you were first starting out, you worked under the great Bill Greaves. What did you take away from working with him?

SN

I worked with Bill. Well, I actually worked for this program called CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act), which was a government program. So I got to work with Bill and Bill didn’t have to pay me. That was the only reason he gave me a job, and he was very clear about that. “I don’t have to pay you? Okay, you can work here!” He didn’t pay me for six months, and the government paid me when I worked with Bill. I learned a lot from him. Bill worked hard, hard, hard. Bill worked hard. I learned that. He was also independent. I saw a Black man, who was independent, who was raising a family with two young girls. He had a house in the country, and he was doing this from making films. He knew every piece of making films. He knew editing, sound, he would shoot some of the stuff himself. I saw that. It went into me by osmosis. It wasn’t like Bill said anything, it was just what I saw.

JF

Was it an economic necessity for him, that he had to be self-sufficient? Or an artistic desire to control everything?

SN

I think at that point, when I went into it, we knew in our guts that that was the only way. I wasn’t going to get a job as a producer at NBC or CBS. That was just not going to happen. I wasn’t the type of person who could get a job as an intern at CBS and then ingratiate myself and work my way up through the ranks. So what’s the other way to do it? Be independent and figure out how to make films in that way.

JF

What was the original impetus for creating the Firelight Documentary Lab?

SN

It was created out of the fact that, when I got into filmmaking in the ’70s, there were a bunch of different programs to help people break into film. WNET had a program, among others. The country that we have now focuses on scarcity instead of the abundance that we really have. All of these programs have gone away. I realized all these filmmakers were calling me about being a mentor to them and filmmakers were calling other people to be mentors for them. I made a film years ago about academics of color in major institutions. And one of the things they all talked about is how they’re asked to be mentors in a different way than white professors are, and that they’re expected to be mentoring. You don’t get paid more, it’s just one of the expectations that you have. I think it’s the same with filmmakers of color—you’re expected to be a mentor. It’s not on me, it’s any filmmaker. We felt that maybe there’s a way to institutionalize that and give it a home. That’s where we came up with the idea for the lab. The thought was that there’s enough filmmakers of color with great projects and the chops to get it done, and there’s money to raise that we can help support this. Both things have proven to be true. We’ve been able to do this for ten years, and I think there’s 80 graduates of the lab at this point.

What we are forming is a community and that’s really important to people. That they’re not by themselves, that there are other people they can talk about cuts to. We try to be very clear because people talk about this golden age of documentary all the time, and it’s a golden age for a few. It’s a golden age for us here at Firelight, because I’ve been doing this for many years and I’ve got this track record. We have this place which we love and it’s beautiful. But we have people in the lab who have done their first film, they win Peabodys and duPonts, awards at Sundance, and they can’t get in the door with distributors. Because they don’t have that name. And again, these are big corporations. It’s a business for them, so they … what’s the word? They want to limit their liability. So how do you limit your liability? You hire Stanley Nelson. You hire Alex Gibney. That’s how you do it.