How Does It End? Story and the Property Form

Brett Story

In this documentary a wrongfully convicted African-American man serves over two decades in prison before new evidence offers his first chance of freedom.

In this documentary a musical prodigy becomes a pop sensation, gets harassed and mismanaged by a rotating cast of shitty men, before losing her life to drugs.

In this documentary a group of underprivileged school children compete in a national competition while navigating turmoil at home and in the classroom.

In this documentary a charismatic elite athlete embarks on the most ambitious—and dangerous—physical feat of his career (and the cinematography is incredible!).

****

Do you recognize these films? You have seen them, and yet you can’t be sure that the film I describe is actually the film that you saw. No matter. Each one fulfills the promise to its audience and to its investors: a nonfiction narrative that takes the form of a story. Main character. Three acts. Heroic journey. Climax. Resolution. Nothing else seems to suffice in today’s documentary marketplace. A good story reigns supreme. The mainstream success of these films—regardless of which particular manifestation of the loglines above we’re talking about—is inevitably marshalled as proof of point. Some of these films won Oscars.

The hegemony of story in today’s documentary field is anecdotal but convincing. Documentary filmmakers, including myself, are constantly asked for “story” at the variety of junctures that enable the production and distribution of their films. And while non-linear, amorphous and boundary-defiant forms have at many historical moments dominated the landscape of nonfiction cinema, this diversity has gradually been eclipsed by an onslaught of documentaries whose narrative waveforms seem to all track along the same contours.

To be sure, a film wants to move from point to point through time, regardless of whether the material is fiction or nonfiction. Form is the structure that organizes this movement, and thus mediates, alongside other aesthetic decisions, the viewers’ experience of the material itself. That it should be story—as opposed to, say, poem, collage, diary, essay, meditation, or any other formal approach—is a curious, and historical, development.

Why has story—in its conventional sense of a linear ordering of anticipated components including character, plot, setting, conflict, and theme—become the documentary world’s most privileged, some say unassailable, narrative form?

On the one hand, the answer is easy. Story appeals precisely because it is deemed outside of material history. Story and storytelling, we’re told, are “as old as mankind.” Story is natural, primordial, and universal all at once. It conjures a pantheon of liberal fantasies about a world of self-contained, auto-generating and freely circulating “truths” that connect humanity and transcend history. And like the word “community,” it virtue signals; nobody takes issue with a story.

But the ascendance of story as documentary’s favored narrative form is not, in fact, natural, predestined, nor outside of history. Story has a political economy, and we can best discern its contours and its consequences by comparing it with its (perhaps surprising) likeness in the realm of law and commerce: the property form.

Let me tell you where the idea for this essay first began. It started at a screening for a film I made about the US prison system called The Prison in Twelve Landscapes, held on the campus of a private elite college a number of years ago. One afternoon a group of us gathered to discuss the film as well as other events and performances that had taken place over the previous few days. A student held up her hand and offered a critical rebuke to my film. The gist was that she considered the topic itself out of bounds to me as a maker. “This is not your story to tell,” she said gravely, pushing back against what she clearly considered an inappropriate appropriation of narrative territory.

I understood the critique and the context from which it emerges. Documentary has from its very origins yielded to some of the worst impulses of racism and classism, cultural appropriation and exploitation of the marginalized, and it continues to do so with unacceptable frequency. A preference for social victims that dates back decades and continues to be a staple of the realist documentary today has underwritten, systematically, the pernicious exploitation of less powerful communities under the guise of a documentary’s social good.{1} People make incomes and careers producing films about communities they are not a part of, do not understand well, and are not accountable to. The stakes and vulnerabilities attendant to documentary’s real world subjects tend then to be unevenly distributed, with the risks borne by those on screen and any benefits accrued mostly to the filmmakers or their distributors.

In this case, this student was certainly invoking this tendency, by questioning my right, as a white woman, to make a film about a system of violence whose burden is disproportionately borne in the United States by African Americans. But while I respected the underlying political impulse of this critique, and suspected that this young woman and I shared some important political commitments, something about the exchange still felt like it missed the mark. And precisely because I wanted to be sure it wasn’t simply defensiveness that was giving me pause, I have been thinking about this conversation ever since. What I realized, finally, was that what bothered me most was the description of my film’s subject matter as a “story.”

In fact, I had for many years struggled to make this film precisely because it did not tell or even feign to tell a “story” at all. The Prison in Twelve Landscapes has no plot, no central character or even central community that drives its narrative forward, no dramatic arc propelled by cause and effect, no set of chronological events or decisive moments—and that is, precisely and formally, its point. The film is instead structured through twelve discrete, often oblique vignettes set in a variety of non-prison spaces, like a coal town or a chess park, edited together to portray the vast geographic reach and institutional breadth of the US prison system. An associative essay film, its committedly non-linear narrative structure suggests we consider the prison not through protagonists or dramas at all (as those tend to reify the system as a whole), but through a multitude of ordinary landscapes, each host to pernicious racial and economic violence.

THE PRISON IN TWELVE LANDSCAPES (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Given, then, that there was no story, how could it “belong” to anyone? The notion of belonging, as it was being invoked in this case, did not refer to responsibility, for surely then the problem of carceral violence could and should be a subject for white filmmakers, or those otherwise privileged by a racist prison system, to take on. This thought led to the next: Since when did “story” become synonymous with “ownership” in the propertied, market capitalist sense?

The unassailability of story as documentary’s assumed and incontrovertible vocabulary, it seemed, had in fact assailed me at both ends of the film’s life cycle. I was forced to make my film without a producer or much of a budget, having failed, on numerous occasions, to convince various funders—even those whose specific mandates are social issue-driven—to underwrite a project that resisted reducing the US carceral state to an easily discernible story. This is precisely what made the very conceit of the film, as well as its politics, illegible within much of the documentary mainstream until its completion. I was interested in using cinematic form to consider the workings and wreckage of a regime, not tell a sentimental story about guilt or innocence, but as a result I found very little traction for its production. I pitched the film at meetings, I described it in grants, I talked about it at festival networking events, and at every pivotal moment, the same question: yes, but where is the story?

I’d gotten used to the question qua accusation in documentary industry spaces over many years of doing this work, and have come to develop a thick and stubborn skin. But it was the invocation of this particular frame by a young, politicized person attempting the necessary work of holding documentary accountable, that had me really start thinking about how story has come to operate as a property form and in the process, has annexed an entire documentary imaginary and discourse.

A story—as we have come to use that term—belongs, confers rights, can be exchanged, and is invested with value. A story is mine or it’s yours. Stories are bound, if not always by a beginning, a middle, and an end, then by some variation of this structural edifice. We trade them or share them or, increasingly, we sell them. Story’s resemblance to property, in these ways and others, is instructive.

Holding story up against the property form and scrutinizing their likeness reminds us that just like property, story is neither natural nor inherently valuable. Its reification as such, however, might just tell us something about the current state of the documentary field, the aesthetic and cultural consequences of documentary’s growing share of the entertainment marketplace, and the political costs of issuing documentary critique through the circumscribed frame of individuated property rights.

****

Property is a Relation

While the idea of property was once capacious enough to encompass regimes of shared stewardship, in the tradition of Western liberal capitalism property has become almost entirely synonymous with private ownership. The ownership model of property assumes a discrete individual with an exclusive right to possess a thing. Property’s realization as a right of possession, and its rootedness in land and law is evidenced, for example, in the common usage of a phrase such as “It’s my land and I can do what I want with it,” and laws like “Stand Your Ground” that render that sentiment enforceable.

In a capitalist society, property is also more than just the object of ownership, but an organized and enforced set of relations, primarily between people, in regard to a valued resource. Property confers rights. As a relation, property organizes much of the contemporary world. It does so legally and socially, but also ideologically. It assigns resources to owners, it allocates rights and duties, and it serves as the grounding for a great deal of contestation and protest. The propertied classes, under capitalism, by definition have more power than the dispossessed.

A typical property leasing agreement, as economic geographer Nicholas Blomley points out, often includes the provision that a tenant be assured of the “quiet enjoyment of the land.”{2} Quiet, here, refers not so much to the absence of noise, but rather the absence from interference and interruption, disturbance and dissention. Property, as a right rather than a thing, grants the promise of fundamental separation. Whatever else property is, it is individuated and enclosed, precisely so that it forms an entity amenable to transaction.

In order to enter the marketplace as something economically transferrable within the capitalist logics of distribution and exchange, property must be commodified. It is only as a commodity that a piece of territory, or an object, or even an idea (think, for example, of patents) can be bought, sold, or exchanged. Property as an ontology does not magically inhere to the commodity form; it must be invested and disinvested with particular characteristics, such as clearly defined boundaries, valuation in monetary terms, and an enforceable means of delineating ownership— i.e., deeds or rights. These rights are used both to create commodities, and also to justify the allocation of (often public) resources to the policing of their boundaries.

Imagine trying to sell a patch of ocean water, or rain from the clouds. Water resists commodification precisely because it is, by definition, fluid, in both form and geography. To make it ownable, and therefore sellable, capitalists have had to bottle it. Once bottled, or purified, or piped, the use of such a resource without payment can be deemed—as in the ongoing case of Detroit’s massive water utility shut offs—a theft, policed and punished accordingly.

Figure 1. Thomas Gainsborough, MR AND MRS ANDREWS (c. 1750), commissioned to celebrate a marriage and the prosperity resulting from the merger of two fortunes. In the background, recently enclosed lands. Courtesy of The National Gallery, London.

Figure 1. Thomas Gainsborough, MR AND MRS ANDREWS (c. 1750), commissioned to celebrate a marriage and the prosperity resulting from the merger of two fortunes. In the background, recently enclosed lands. Courtesy of The National Gallery, London.

Property rights in the context of western capitalism thus tend to rely on two pivotal processes: privatization and enclosure. Enclosure, historically, is a materialist as well as ideological practice, involving the expropriation of a bounded resource and the removal of that resource from the commons. In its most literal sense, enclosure refers to land, which, as the historian Peter Linebaugh reminds us, was once held in common for shared use, whether for leisure or labor.{3} When in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries industrializing nations like England and the United States began to systematically parcel out and patrol the commons into private property, those whose livelihoods relied on shared access to this land experienced a new form— indeed, a systematic regime—of impoverishment.

The enclosure of lands was then, as it is now, the people’s loss. Enclosure and privatization were necessary tactics of the newly industrializing capitalist (and colonial) classes, as lands held in common, for the toil and sustenance of many, proved an inherent bulwark against the accumulation of profit. But Linebaugh suggests that enclosure doesn’t only refer to land:

Besides land, enclosure may refer to the hand. Handicrafts and manufacturers were enclosed into factories, where entrance and egress were closely watched, and women and children replaced adult men. Allied with enclosure in the factory was the enclosure of punishment in the prison or penitentiary.{4}

The most important lesson is the centrality of enclosure practices to the capacity of capitalists to extract profit from the valued resource, whether that resource is land or the indentured laboring body. And while historically the resource has had physical presence, the commodity nature of those materials has always been fictitious, indicating, instructively, that any resource deemed financially valuable can be transformed into commodity form.

Even—or perhaps especially—story.

****

Festivals, Markets, and the Monoform

Distributors, programmers and filmmakers tend to speak in hushed terms about the changing political economy of documentary production and distribution, but generally agree that it hasn’t been good for independent artists and smaller players.{5} The growing influence of big buying conglomerates like Netflix have so far portended both the shrinkage of distribution opportunities, as smaller and more adventurous distributors are forced to pay to play or get bought out, and the homogenization of festival catalogs. Programmers at prestige festivals with major markets are increasingly pressed to program films with big sales potential, albeit to fewer and fewer buyers, or to program films already purchased by the major broadcasters and streaming sites who see awards advantage in playing at least one or two big festivals.{6} The pressure isn’t necessarily direct, as the industry and programming sides of a festival may be somewhat siloed from each other, but the increasing corporatization of many festivals, and growth of their sponsorship teams, means that programmers do end up internalizing market prerogatives as they make their selections. As one former director of programming of a major documentary festival told me “curators are leaning toward the market more than ever.”{7}

The amount of space ceded to “pitch forums” and “meet markets” at film festivals, including those festivals focused exclusively on documentary, also point to the outsized influence that funders and buyers have in determining the documentary field. Indeed, industry-oriented programming, including a bevy of networking events meant to put directors and producers in greater proximity to possible buyers, seems to grow even while resources for filmmakers and their collaborators shrink. The result: documentary filmmakers hustle to get their films into A-list festivals like Sundance or Berlinale in order to find buyers, sales agents make conservative calculations about which films will get into the handful of festivals with major markets and drop the ones that don’t, and the films whose forms most resist commodification disappear into the ether.

This disappearance is either not registered for those in the documentary mainstream, or dismissed as inconsequential, much like the adjective “artistic” is used derisively, to undercut rather than underscore a documentary’s claim to value. In my own experience pitching films, “artistic” has only ever been a dirty word, synonymous with commercial irrelevance, vain indulgence, or a sign of fanciful priorities. In the documentary mainstream, “art” and “story” are increasingly positioned as antipodes.

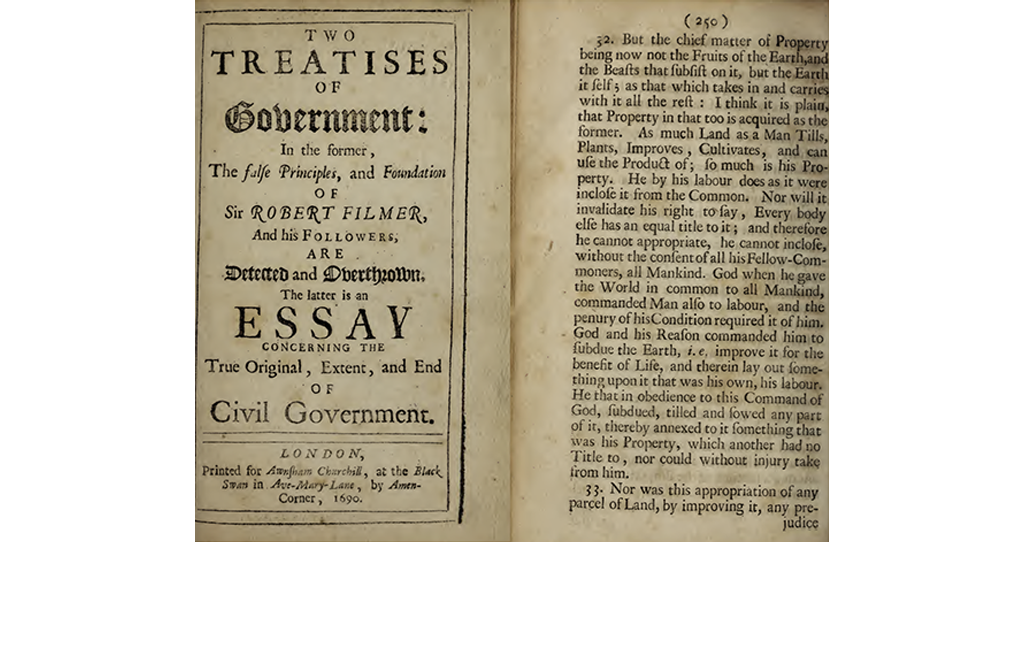

Indeed, the history of propertization remains instructive. During the colonial conquest of Indigenous lands in the Americas, as elsewhere, enclosure was justified in part through the British philosopher (and investor in the slave trade) John Locke’s doctrine of “best and highest use”: deeds to newly enclosed land were offered to those who could prove that they were using the land “best.” These people were always, without exception, white settlers. Justification for outright plunder was thus veiled by moralist (and racist) appeals to the Enlightenment idea of improvement. So long as settlers could say they were “improving” the land by laboring on it to create surplus wealth, they could claim jurisdiction over what otherwise belonged, through stewardship, to Indigenous peoples.

Storytelling is documentary’s own claim to highest and best use—in this case, of actuality.

This has become especially true in the internet era of seemingly endless moving-image content. For example, those who follow the comings and goings of the movie trade know that the Tribeca Film Festival was recently sold. The entertainment site Indiewire reported the sale of the festival in late 2019, noting, with some surprise, that the buyer was a holding company owned by the infamous Murdoch family. Why would the Murdochs, known for a sprawling right-wing media empire that includes Fox News, want a ten-day film festival in the heart of liberal New York? The answer was in the headline: “Storytellers, Curators are Big Business.”{8}

Figure 2. Kate Erbland, “James Murdoch Leads Controlling-Stake Buyout of Tribeca Enterprises, Including Film Festival,” Indiewire.com, August 5, 2019.

Figure 2. Kate Erbland, “James Murdoch Leads Controlling-Stake Buyout of Tribeca Enterprises, Including Film Festival,” Indiewire.com, August 5, 2019.

The purchasing company’s CEO, Joe Marchese, rationalized the acquisition in these terms: “The next most exciting part about the Tribeca brand is its incredible potential. In a world where amazing stories are getting lost in a sea of ‘content’ and filters are determined by AI, there is a massive market opportunity for curators.”{9} In other words, as Indiewire put it, “curation is a compelling business model in the attention economy.” Stories are such hot commodities that the work of discerning between them offers its own exploitable profit margin.

The intersection of moving images and market capitalism, of course, is nothing new. Movies have always been commodities. And so long as movies have proven able to make money, filmmakers and their financiers have competed for the time and attention of audiences. In the case of documentary, some date the profiteering back to Nanook of the North (1922) and Robert Flaherty’s intensive and successful fundraising efforts. But the real watershed was probably closer to the late 1980s and 1990s, when films like Hoop Dreams (1994) and Roger and Me (1989) were released in theaters and proved that documentaries too could offer big box office returns.

When Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 hit multiplexes in 2004, it became not only the largest grossing box-office documentary in American movie history but one of the top ten grossing films of the year.{10} Over the past two decades, profits at the box-office for documentaries like Spellbound (2002), Searching for Sugarman (2012), and Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (2018) have signaled to investors that documentaries were worth paying attention to. Cheaper to make than most narrative films, and associated in their public image with noble causes like education or social change, documentaries have become increasingly attractive to a variety of financial players, including studios, equity investors, and streaming services. When Netflix bought the documentary Knock Down the House in 2019 out of Sundance for a record breaking $10 million, many of the industry folks I spoke with concurred almost instinctively with the view that the film’s director, Rachel Lears, had scored big by picking the right protagonists. The unlikely rise of the film’s star, the democratic socialist firebrand Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, was a fantastic story. The dollar sign doesn’t lie.

The presence of these players has changed the field, as well as the work. Those following documentary trends, including the handful of producers, distributors, and programmers I surveyed in writing this piece, agree that the commercial success of a growing roster of documentaries has had profound effects on the state of the industry, and thus on the conditions underlying documentary film production itself.{11} As filmmaker and scholar Irene Lusztig notes, “the success of this small number of profitable documentaries was pivotal in setting in motion a certain set of aspirations or expectations about what documentary might do in the marketplace.”{12}

It is precisely those “aspirations and expectations” for documentary’s profitability, and their consequences for the form and aesthetics of documentary cinema, that is of concern. If curation can be bought and sold as a business model among those who have already monopolized the media field, what of the cinematic idiom itself? Indeed, festivals aren’t the only ways in which attention is purchased, packaged, branded and sold. The monoculturing of form is another tactic in the entertainment marketplace. And “story,” as a proven narrative formula, seems to have become the monocrop of the twenty-first century documentary landscape.

The result is not just increased homogenization and risk aversion within the documentary landscape, but a bonafide obsession—among funders, producers, programmers and distributors—with insisting on story in whatever documentary they are positioned to greenlight. What is now, at least in hindsight, revered in cinematic nonfiction—adventurous formal and aesthetic explorations in films by Agnes Varda, Chris Marker, Chantal Akerman, Werner Herzog and many others—has given way in this “golden age of documentary” to more formulaic, and considerably less imaginative, treatments of actuality. So where once a filmmaker like Frederick Wiseman could find support and distribution for a portrait of everyday life in a department store, or a radical work of non-linear assemblage like Handsworth Songs could find a platform on a major British broadcaster like Channel 4, today’s documentary filmmakers must negotiate fragile careers and mounting debt under the unrelenting sign of the story form.

But what are the stakes of all this, other than the struggle of makers to be allowed more range and risks in the making of their works? What does story, as the mold within which we are asked to submit actuality in our cinema, have to do with politics?

Quite possibly, everything.

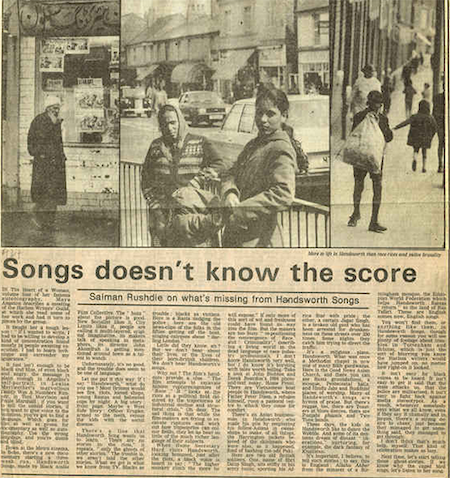

Let’s take Handsworth Songs as an example. When the film was broadcast on British television in 1986, not everyone was so impressed by the montage approach of its makers, a group of radical Black British artists known as the Black Audio Film Collective. An experimental “report” on post-migration Britain and the large-scale unrest that erupted following the police shooting of an Afro-Caribbean woman in Margaret Thatcher’s England, Handsworth Songs was lambasted by no less a prominent public figure than the novelist Salman Rushdie. In his review for the Guardian, Rushdie accused the film of failing to tell positive, postcolonial stories about British migrants, and lamented the film’s privileging of experimental form and thematic preoccupations over sympathetic depictions of individual characters:

The trouble is, we aren’t told the other stories. What we get is what we know from TV. Blacks as trouble; blacks as victims . . . But we don’t hear about their lives, or the lives of their British-born children.{13}

Story parades as limitless, but in effect it circumscribes what’s possible, in discourse as well as in social life. That Rushdie’s critique resonated so neatly with the very crux of then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s ideological project—a project that vastly intensified the very power inequities that Handsworth’s residents were protesting and which Handsworth Songs attempts to demystify—tells us as much. “There is no such thing as society,” Thatcher declared in 1982, seeking to justify her government’s fulsome assault on unions, social housing, and the public sphere more broadly, “only individuals, and their families.” One hears in Rushdie’s criticism an echo of that same neoliberal prerogative: “Only individuals, and their stories, please.”

Figure 3. Salman Rushdie, “Songs Doesn’t Know the Score,” GUARDIAN, January 12,

1987.

Figure 3. Salman Rushdie, “Songs Doesn’t Know the Score,” GUARDIAN, January 12,

1987.

The story form as it is most commonly heralded—owned, belonging, contained, resolvable—does useful work for capital recuperation precisely because it dovetails with the individualism at the heart of neoliberal capitalism and the property form alike. The hero, the resilient individual, the villain, the charity case: these are all variations on an already existing and pernicious ideological preference for the individual over the social, the “character” over the condition, experience over consciousness.

Here we find ourselves returned to John Locke, who was not only among the first modern theorists and proponents of property, but was also among the first philosophers of the person as individual. Indeed, Locke’s conception of property is itself anchored in a theory, forged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, of the autonomous and atomistic subject, one whose being and status in the world was the result of his self-determination. According to this ontology of personhood, one is the owner and the author, first and foremost, of oneself. Such a subject is central to contemporary liberalism, to market capitalism, to the modern literary novel, and, arguably, to documentary storytelling. It makes possible the category of the victim, as well as the hero.

There are political as well as aesthetic stakes to these musings. As the filmmaker RaMell Ross points out when he explains his resolve to construct his film Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018) entirely out of what he describes as b-roll, the idea of the all-important “decisive moment” in image-making aligns uncomfortably with a long history of blaming African Americans for their own marginalization, under the mantle of “bad choices.”{14} So-called ownership over one’s social conditions offers cover for the forces of structural oppression, which documentary images then reinforce with their privileging of protagonists in action.

To center an individual and their story is also to center, in our cinema, empathy over solidarity. And the only thing wrong with empathy is its political limits. Liberation, the historian Robin D. G. Kelley reminds us, is a shared project, one that requires more than the transaction of experiences. Empathy “pivots around taking a singular story, someone’s singular experience, and then, from that, projecting out. As if that singular experience—empathizing with the individual—then allows us to understand everyone who might be suffering from a particular set of circumstances or struggles.”{15} Solidarity, in contrast, is more capacious, and thus more radical, precisely because it takes as its prerequisite not just recognition of oneself in another self, but a view, however achieved, onto shared conditions and common cause.

When the cultural critic Stuart Hall came to the defense of Handsworth Songs shortly after Rushdie’s scathing review, his rejoinder hung on the insight that images fold back on material reality; they can either reproduce, or they can interrupt, the frameworks that then circumscribe what is knowable. “What I don’t understand” Hall wrote, in his response in The Guardian, “is how anyone watching the film could have missed the struggle which it represents, precisely: to find a new language.”{16}

An image, an edit, a sound—all tools of representation—operate as indexes to ideological themes. The language of the mug shot doesn’t just convey an image of a person but also reinforces a particular framework—the category of the criminal, for example, or the equation of criminality with danger—through which that person becomes “known.” Images have responsibility for far more than just expanding knowledge about anything; they organize the very ideological frameworks that determine what can even be known.

As Bradley Bryan observes, “our ideas of property seem to be present in much of the way we comport ourselves with respect to each other and to the world.”{17} Once reality is reduced to stories, and stories reified as discrete, enclosed, and individually owned, then all those aspects of a shared reality that we otherwise still hold in common—spaces, systems, ideology, history—get erased from the actuality deemed worth considering in cinematic terms. And as Ariella Aïsha Azoulay suggests, after centuries of imperial warfare and plunder, our most persistent and pervasive common of all might be violence itself.{18} From this perspective, a documentary culture in thrall to the story form can continue to tell gripping narratives and fill theatres, but finds itself impotent to represent the structures of violence that bind us together.

In its evisceration of the social in favor of the individual, the story as a property form itself performs a kind of injury, the injury of commodification. The process of turning something into property by definition requires the suppression in a given resource of any value that cannot be quantified or translated monetarily. The fictitious commodity of land in liberal capitalist society, for example, entails that market value supplants all other values. That erasure is what makes us all poorer. Because property organizes private ownership and market transactability, it is at once anti-social and scarcity-inducing. So, while the nineteenth century anarchist slogan “property is theft” has caught on among today’s anti-capitalists, it is French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s definition that perhaps proves most prescient: property is the suicide of society.

Story, as a property form, not only submits to the ideological axiom of individuated life, but subsumes all critical discourse into a framework that by definition precludes the possibilities of a common sphere. Even the etymology of property is instructive: Middle English: from an Anglo-Norman French variant of Old French propriété, from the Latin proprietas, from proprius “one’s own, particular.”

We do ourselves a service then, as a documentary community, to consider what is lost when we demand, and then interpret, all non-fiction cinema through the framework of story.

****

Forming the Commons

Contrary to popular opinion, story is neither neutral, nor incontrovertible, but socially mediated. And if it behaves like property, it is because we’ve trained it to.

Property is what is left when whatever resource deemed valuable is confiscated from the commons. Story-driven documentary—as model and coercion—inherits and extends the logic of the property form. In so doing, it seems, story is in danger of subsuming all possible discourse, including radical critique, into the framework of individual property rights.

The result is that social reality itself, the real that might be creatively calibrated, destabilized, or reimagined through the cinematic art of nonfiction, becomes its own standing reserve for human rationalization. Contestations over turf, rather than projects of collective action, then become the sole horizon of progressive politics.

To be clear, there are many real and urgent ways in which we must continue challenging racism, appropriation, and extractive filmmaking in documentary. I’m just not convinced that invoking the logic of property offers the most transformative or even meaningful means of doing so. When we talk about someone’s story, or refer to a subject as a story, owned or belonging to, privatized and enclosed, we are ceding not so much to insurgent critique as to market liberalism. And market liberalism, as I’ve argued, is much more invested in story’s privileged status within the field of documentary’s formal possibilities than we might care to acknowledge.

This is something that radical and socially committed cultural producers should challenge at every juncture. But more than that, we might consider what kind of documentary forms might correspond to collective commons. Perhaps, by definition, such forms are limitless. And that is both their point, and their promise. As the opposite of privatization, individualism, commodification and conquest, forms that correspond to the commons might be capable of being measured only by their resistance to domestication. For they bow not to the almighty sign of the dollar, but to the ongoing struggle of liberation: boundless, abundant, unquiet.

Background Video: The Prison in Twelve Landscapes (Brett Story, 2016) / Handsworth Songs (Black Audio Film Collective, 1986).

{1} Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 3. See also Brian Winston, “The Tradition of the Victim in Griersonian Documentary,” in Image Ethics: The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film, and Television, eds. Larry Gross, John Stuart Katz, and Jay Ruby (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 34–57.

{2} Nicholas K. Blomley, “Mud for the Land,” Public Culture 14, no. 3 (September 2002): 557–582.

{3} Peter Linebaugh, Red Round Globe Hot Burning: A Tale at the Crossroads of Commons and Closure, of Love and Terror, of Race and Class, and of Kate and Ned Despard (San Francisco: University of California Press, 2019).

{4} Ibid, 3.

{5} Since the 1970s, Peter Watkins has used the term “monoform” to denote the “time-and-space grid clamped down over all the various elements of any film or TV programme. This tightly constructed grid promotes a rapid flow of changing images or scenes, constant camera movement, and dense layers of sound.” See Peter Watkins, Media Crisis (Paris: L’échappée, 2015), or http://pwatkins.mnsi.net/dsom.htm.

{6} While my evidence on this point is anecdotal, the very taboo nature of the topic makes verification difficult. Recent public remarks by exiting festival programmers, however, also insinuate the market-driven nature of some programming choices. See for example: Luke Moody and Nick Bradshaw,“‘The Chimney Needs Sweeping’: Luke Moody

on the end of his tenure programming Sheffield Doc/Fest,” Sight & Sound (July 2019); and Abby Sun, “Withdrawing To and Withdrawing From: Notes On The 65th Robert Flaherty Film Seminar,” in Action: The 65th Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, ed. World Records (New York: International Film Seminars, November, 2019), Exhibition catalogue.

{7} Interview with Sean Farnell, former Director of Programming at Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival.

{8} Chris Lindahl and Dana Harris-Bridson, “Tribeca Sale: From Robert De Niro and Jane Rosenthal’s Festival to ‘Attention Economy’ Player,” Indiewire, August 6, 2019.

{9} Ibid.

{10} Andrew Horton, “Documentaries Hit the Multiplexes, Cinematic Views 79, no. 3/4 (2005): 68–69.

{11} Most of the conversations that inform this piece were informal, but I did consult a half dozen former programmers, distributors, and producers with questions specific to the claims made in this essay.

{12} Written as a Facebook comment in November 2019 in response to this author’s query about the political economy of documentary, and quoted with permission of Irene Lusztig.

{13} Salman Rushdie, “Songs doesn’t know the score,” Guardian, January 12, 1987. Reprinted in Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-91 (London: Granta, 1991).

{14} RaMell Ross, “Toward Subjectivity,” Lucy Molnar Wing Lecture at Ryerson University School of Image Arts, November 1, 2019.

{15} Robin D.G. Kelley, “Solidarity is Not a Market Exchange,” Black Ink, January 16, 2020.

{16} Stuart Hall, “Song of Handsworth Praise,” Guardian, January 15, 1987.

{17} Bradley Bryan. “Property as Ontology: On Aboriginal and English Understandings of Ownership.” Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 13, no. 1 (2002): 3-32.

{18} Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso, 2019), 148.