Documentary’s Longue Durée: Reimagining the Documentary Tradition

Joshua Glick, Charles Musser

An increasing variety of documentaries across small and large screens demands new forms of attention from media critics and scholars. Recent writing engages documentary from at least four perspectives: as a revenue stream for mega distributors-turned-studios within the Hollywood-Silicon Valley nexus; as an artistic practice for investigating how modes of representation shape everyday experience and knowledge of the world; as a form of political critique and a social organizing tool for activists; and as an emerging media frontier for “immersive” storytelling, inflecting everything from journalism to public history and gaming.{1} At the same time that questions concerning the economics, ethics, and aesthetic craft of contemporary documentary have fueled a flurry of reviews, manifestos, white papers, festival summaries, and academic journal articles, they have also pointed to new avenues for exploring the past.{2} Scholars have also been rigorously historicizing twentieth-century documentary criticism and theory as well as analyzing nonfiction production across media, including 16mm film, digital photography, and audio recording technologies.{3}

Documentary filmmaker and media scholar Charles Musser’s current project, a book tentatively titled Film Truth, Documentary Practice, sets out to complicate this shared historical endeavor. His project interrogates the commonly articulated temporal and medium-specific bounds of the “documentary tradition.” Musser investigates a practice of publicly performed pedagogy that long predates the widespread use of the term “documentary” as applied to nonfiction screen practices in the late 1920s–30s. He analyzes what he calls documentary’s longue durée, locating its formation in the Enlightenment as discourses of “science” and “reason” provided an alternative truth to the word of God. Musser toggles between a fine-grained analysis of the secular lecture (a term that had been primarily associated with the religious sermon until the early 1700s), its frequent reliance on a diversity of illustrative materials (models, panoramas, recitations, lantern slides, and more) and a broader study of technological transitions and the emergence of mass communication industries. The incorporation of media archaeology into the project places the study of documentary in productive dialogue with currents in intellectual, legal, and economic history, in turn opening up fresh, interdisciplinary approaches to the role of documentary in the public sphere today. Additionally, focusing greater attention on the material culture of documentary production, distribution, and exhibition contributes to a deeper understanding of our current moment of heightened digitization, media convergence, and networked devices.

–Joshua Glick

Conversation

Joshua Glick

Although we have a lot of overlapping teaching and research interests, our current book projects are moving in quite different directions. Help us to understand some of the central contours of your project. Can you sketch the general background of the book and where it exists in the field?

Charles Musser

If we look back at the documentary field over the last thirty or so years, what has happened is quite impressive in several different areas. First, there has been an amazing surge in the number, quality, and diversity of documentaries—and of documentary practices. The appearance of digital media has had a lot to do with this, but there were also important conceptual breakthroughs in the 1980s, which preceded that new media technology. Second, there has been important scholarship that approaches documentary from a theoretical perspective—catalyzed by people such as Bill Nichols, Michael Renov, Jane Gaines, and David MacDougal. The history of documentary is another matter. There have been a few workmanlike overview histories that are mostly histories of films, specific filmmakers and movements; but I still assign Erik Barnouw’s Documentary: A History of Nonfiction Film (1974) to my students. The field of documentary has become so vast that case studies have become the principle way of dealing with this problem of scale. Your valuable work on documentary film and television in Los Angeles from 1958 to 1977 is an example. Nevertheless, if we delve into what Lewis Jacobs has called “the documentary tradition,” we encounter huge holes and often a lack of connective tissue. Like many of our colleagues, I have been investigating some of these gaps in our historiographic knowledge: how can you think about Paul Strand and Leo Hurwitz’s Native Land (1942) without understanding it as a response to Cecil B. DeMille’s Land of Liberty (1939)—and Paul Robeson’s role in both films? How can you think about left-wing documentary filmmaking in the US without dealing with Carl Marzani and Union Films in the decade after World War II? These kinds of investigations are absolutely necessary, but they are not sufficient in themselves.

JG

Certainly the “case studies” approach has had the benefit of localizing documentary within period and place-specific contexts that have enabled us to better understand the strategic uses of nonfiction.

CM

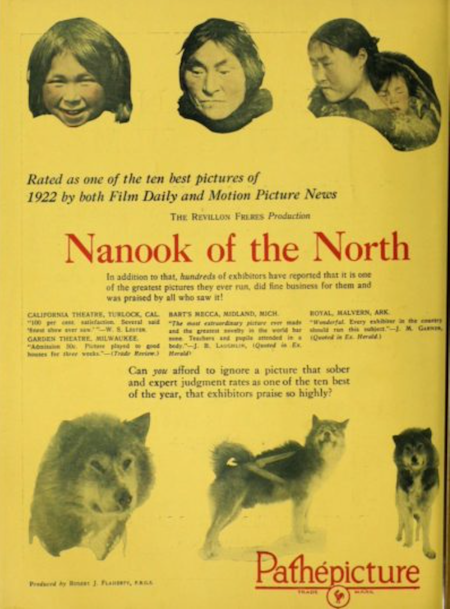

Agreed! Case studies are important but like any approach to a complex field of study such as documentary, they have inevitable limitations. We have tended to neglect what I am now calling the longue durée of documentary. We need to think about documentary as a formation and as a practice that is not arbitrarily tied to the appearance and rapid adoption of that term. And we need to stand back, historically speaking, and put aside our association of documentary with a specific media form— celluloid-based moving image media. We have had few hesitations in applying the term documentary to ongoing practices as we have moved forward from film-based to digital media-based work. It’s going in the opposite direction—looking backwards to the era before film that has posed a set of theoretical and historical challenges that we may only now be ready to engage.{4} Why did the term “documentary” appear when it did, and why was it retrospectively applied to films such as Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922)?

Advertisement, EXHIBITORS TRADE REVIEW, 10 March 1923, (back cover).

Advertisement, EXHIBITORS TRADE REVIEW, 10 March 1923, (back cover).

To see documentary emerging in the 1920s through the efforts of four “fathers” or founders—Flaherty, Vertov, Grierson and Ivens—is remarkably reductive and not just because we should also include Esther Shub. Frankly it’s a mess; and a brief, tentative nod to pre-Nanook “documentaries” does little to tidy up the historical landscape. It makes what we do, what we teach, and what we write about dangerously adumbrated. It is as if art historians agreed that painting began with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Donatello. It is really hard to get on the right track, historically speaking, when one starts off from an originary myth of this kind.

JG

In one sense, your project resonates with the ways historians have been exploring a broader field of nonfiction media that includes travelogues, home movies, instructional films, and essay films. At the same time, you are investigating a history of the documentary tradition that precedes moving and even still images.

CM

The challenge for me has been to rethink documentary’s longue durée in a fundamental way. I began by exploring the many documentary-like screen programs that were flourishing by the 1880s under the rubric of “the illustrated lecture.” These used a succession of projected lantern slides, a lecturer providing commentary, and music. In the early 1910s and beyond there were plenty of illustrated lectures that consisted entirely of motion pictures. These film programs were full-length features. However, as warring nation states required the rapid, broad dissemination of wartime propaganda films with a clear and consistent message, live voice commentary was replaced by intertitles (musical accompaniment of course continued). The results were films such as The Battle of the Somme (1916). This shift from live commentary to intertitles had other sources of encouragement as well. Remember that the film industry proper only began to make feature-length fiction films in the early 1910s and these were only offered with a standard release schedule around 1914–15. Feature-length nonfiction programs, which constituted a widely accepted and well-established form, could only participate fully in this new distribution system with its revenue stream if these films were similarly standardized. One might argue that this opportunity only became fully evident in the wake of WWI—with nonfiction films such as Nanook of the North. Quite obviously, these nonfiction films could not easily be called illustrated lectures because there was no lecture (and no lecturer). Industry promotional materials and reviews indicate that critics and industry figures were really struggling to characterize Nanook and some similar films from this immediate post-WWI period. What should they be called? The term “documentary” conveniently filled that need. Thus, a modest shift in the modes of production and representation created a crisis in terminology. Perhaps if the successful melding of recorded sound to motion pictures had occurred a decade earlier (say with the Edison Kinetophone in 1913), we might not have had the same kind of crisis in etymology—in what to call nonfiction film. This transformation, of course, had other ramifications. Nonfiction media makers no longer had to tour with their programs and present them in person—as Flaherty had done with his pre-Nanook illustrated lectures. Or as Osa and Martin Johnson had done, and Burton Holmes continued to do with his travelogues. These newly identified documentaries were self-contained, independent commodities—something that had essentially happened with fiction film some twenty years earlier, around 1903. This standardization meant that many copies of the same nonfiction program could be shown at the same time, and it gave these nonfiction producers of the 1920s new kinds of creative control and new kinds of freedom. The nonfiction filmmaker no longer had to be a showman-exhibitor. The protagonist of Flaherty’s illustrated lectures was Flaherty. The protagonist of Nanook of the North was Nanook. It was a really remarkable shift. Moreover, to the extent that the history of cinema (and documentary) has been a history of individual films, auteurs, and movements, this transformation gave historians of nonfiction cinema a set of recognizable texts that enabled film historians to focus more on content and less on method. So, I would not argue that the post-WWI moment is less important but rather that an adequate history of nonfiction film practices would produce a fundamentally different account of that decade. It was a moment when nonfiction audio-visual media could function (often only very tentatively) as a form of mass communication and mass entertainment.

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME (1916).

JG

So when can we locate the “origins” of documentary practice?

CM

That certainly is one of the key questions that has been bugging me for a couple of decades. One factor that should already be clear is that both the documentary and the documentary tradition are not media-specific modes. Although the full-on adoption of digital media resulted in significant changes in documentary practice, the resulting works generally remained self-contained audio-visual screen entities that were experienced in ways very similar to pre-digital documentary and so the issue of terminology was never front and center. Likewise, the shift from illustrated lectures using lantern slides to illustrated lectures using slides and film—and then to those only using film—did not produce a change in terminology nor a questioning of underlying generic assumptions—even though there was a clear shift in media which altered the way these works were made, exhibited, and experienced.

JG

Why isn’t literary reportage or the photo book considered to be within this documentary purview. In his classic exploration of documentary ethics and rhetoric, Doing Documentary Work, Robert Coles includes texts such as George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier (1937).{5} And in Documentary in American Television: Form, Function, Method, A. William Bluem looks at early journalistic photography and radio. Is there something special or distinct about the public presentation or performance of illustrated lectures?

CM

Perhaps. But there are surprising, unexpected complexities as we move further back into the nineteenth century; the history of the illustrated lecture and the documentary tradition is not as straightforward as I had at one time imagined. Here is one problem: are documentary photography and nonfiction radio part of the documentary tradition? Well not as Lewis Jacobs was evoking it in his book. And not as I have been sketching it out here. We might need to think of a broad conception of the documentary tradition that includes forms such as radio, photography and the like—the kind of broad impulse imagined by William Stott though he saw it (incorrectly I would argue) largely as a 1930s phenomenon. Then there is the more familiar, narrower version of “the documentary tradition” that is understood as an established, distinct mode of communication and expression. Obviously, what most concerns us here is this narrow form—though it can be reductive to entirely separate the two. Just for example, many documentary filmmakers have also been documentary photographers. To focus on just one aspect of their work seriously distorts their methods and achievements.

JG

Can you say more about what characterizes this documentary mode as a distinctive form of screen practice?

CM

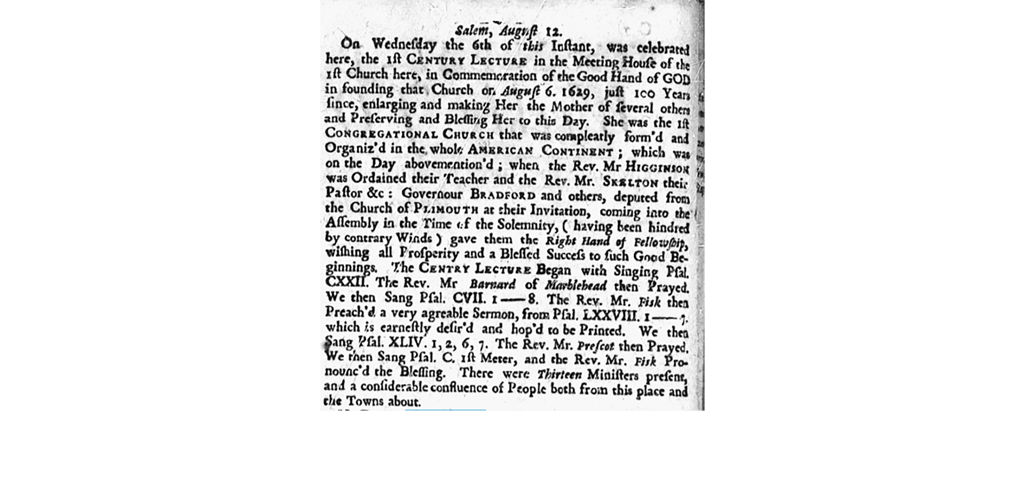

Well, linking the illustrated lecture to the use of projected images, as I have tended to do in the past, turns out to be a big problem as we trace out documentary’s longue durée. We may need to trace out two separate strands of cultural production. The first is the lantern show or audio-visual screen program, which is tied to the invention of the “magic lantern” and was in place by the 1670s. Many of these presentations might be considered nonfiction. Using hand-painted lantern slides, lanternists often offered programs on the life of Christ, while Jesuit priests would later explicate their travels to China and elsewhere. I am not at all sure how we should think about these efforts, although we might want to think of them as illustrated lectures—that would be a retrospective characterization. If scientist and astronomer Christiaan Huygens, inventor of the magic lantern (ca. 1659), and Athanasius Kircher, whose second edition of Ars Magna Lucis et umbrae (The Great Art of Lights and Shadows, 1671) described and illustrated the magic lantern, contributed to the documentary tradition it may be because they were part of the scientific revolution that helped to set the stage for what followed.

Announcement for the 1st Century Lecture at the meeting house for the First Church in Salem, NEW ENGLAND

WEEKLY JOURNAL (Boston), 18 August 1729.

Announcement for the 1st Century Lecture at the meeting house for the First Church in Salem, NEW ENGLAND

WEEKLY JOURNAL (Boston), 18 August 1729.

Announcement for lecture by Archibald Spencer, NEW-YORK WEEKLY JOURNAL, 24 October 1743.

Announcement for lecture by Archibald Spencer, NEW-YORK WEEKLY JOURNAL, 24 October 1743.

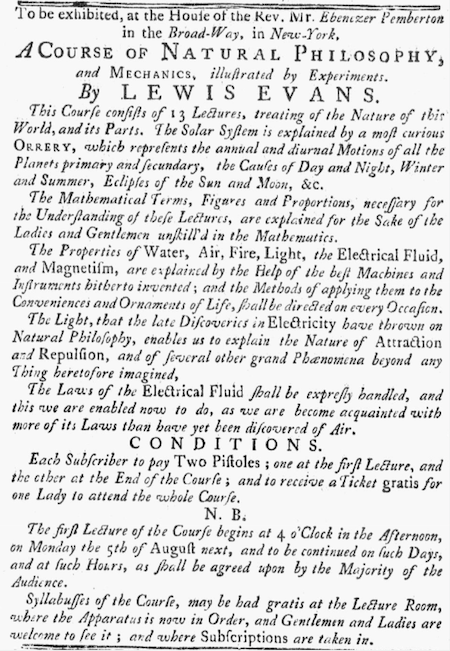

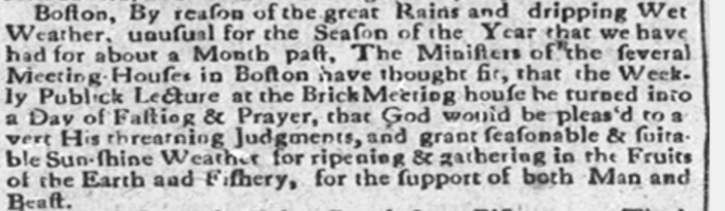

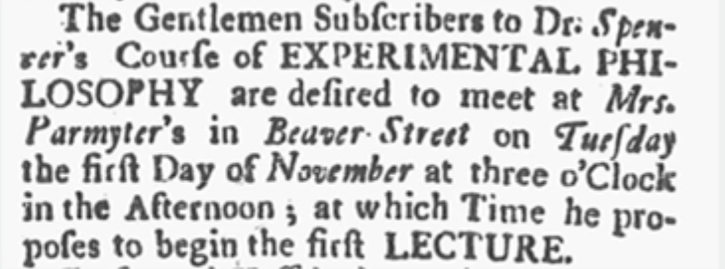

Somewhat surprisingly (to me at least), we need to pursue a second, quite different genealogy—one that is less concerned with both technology and the image (the illustrations of the illustrated lecture), and focuses more on the lecture itself. The term “lecture” appears in early American newspapers as far back as the 1690s. Its usage in this period indicates that the lecture was integrally related to the sermon: it was church-based and religious. People were enlightened by the word of God and a literal interpretation of the Bible. This began to change in the 1740s as the lecture was taking on a quite different meaning—as a vehicle for enlightening people through reason and science. In one early instance, Dr. Archibald Spencer of London gave a successive series of lectures on “experimental philosophy” in the East Coast cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in 1743–44.{6} One prominent audience member, Benjamin Franklin, was inspired to pursue his own experiments in electricity as a result. Similar types of lectures on natural or experimental philosophy became more common after 1751, when Lewis Evans offered “A Course of Natural Philosophy and Mechanics.” The course consisted of “13 lectures” and was “illustrated by Experiments,” including a mechanical model of the solar system.{7} (Audiences in this period were quite small and the courses were often given in prominent homes—rather than in churches. The shifting nature of venues for nonfiction programming obviously needs to be pursued.) This new form of the lecture was a crucial but perhaps underappreciated aspect of the Enlightenment particularly the American Enlightenment. Scholars have generally examined the Enlightenment within the framework of intellectual history that is said to involve a republic of letters with an emphasis on texts and reading. But there was also an interest in enlightening a broader public through means other than books and letters. The lecture was a means of addressing an attentive audience outside of the church—and appealing to human reason rather than religion as a source of enlightenment. Here is what we might consider the founding instance of documentary truth: truth was offered through scientific reasoning and analysis rather than through the enlightenment of God’s word. It was presented to a group—an audience—that allowed for a collective experience in the public sphere.

In what might appear to be a non sequitur, it is also worth noting that another key term that underwent a shift in meaning during this same period was “document.” Once utilized primarily in regards to shipping (as proof of ownership, the vessel’s origins, and its cargo), the term began to take on new meanings within the court of law—at least as reported in newspapers. This new use, in which authentic documents provided evidence in the court of public opinion as well as law, began to appear in the 1740s but was not common until the 1760s. From this soon emerged the term “documentary.” Subsequently, from 1786 the term “documentary evidence” began to be used in British Parliament when charges of treason and corruption were investigated.{9} In due course such accounts were reprinted in American papers. The shifts in meanings for both “lecture” and “document” occurred at roughly the same time. Although these new usages were seemingly unrelated, both suggest an appeal to objective reason, evidence, and enlightenment. Perhaps this needs further thought, but it strikes me that the longue durée of documentary as a formation begins here with the new form of the lecture in which experiments and illustrations served in some sense as documents.

Announcement for the 1st Century Lecture at the meeting house for the First Church in Salem, NEW ENGLAND WEEKLY JOURNAL (Boston), 18 August 1729.

Announcement for the 1st Century Lecture at the meeting house for the First Church in Salem, NEW ENGLAND WEEKLY JOURNAL (Boston), 18 August 1729.

JG

Was there a program of topics covered in these lectures?

CM

Lectures were soon given on a wide range of subjects—not surprising since the American Enlightenment “restored literature, arts, and music as important disciplines worthy of study.” These lectures could be illustrated, but the kinds of illustrations were remarkably diverse: musical passages, recitations, demonstrations, paintings, small scale models and so forth. The magic lantern could be one of these: In the 1820s, a group of lessons or lectures on geography and natural history were “illustrated by the phantasmagoria”—a commercialized version of the magic lantern.{8} However, 1) many lectures were not illustrated, 2) there was no particular affinity between the magic lantern and those lectures that were illustrated, and 3) those lectures that utilized illustrations were not called illustrated lectures.

JG

When did the term “illustrated lecture” first widely appear?

CM

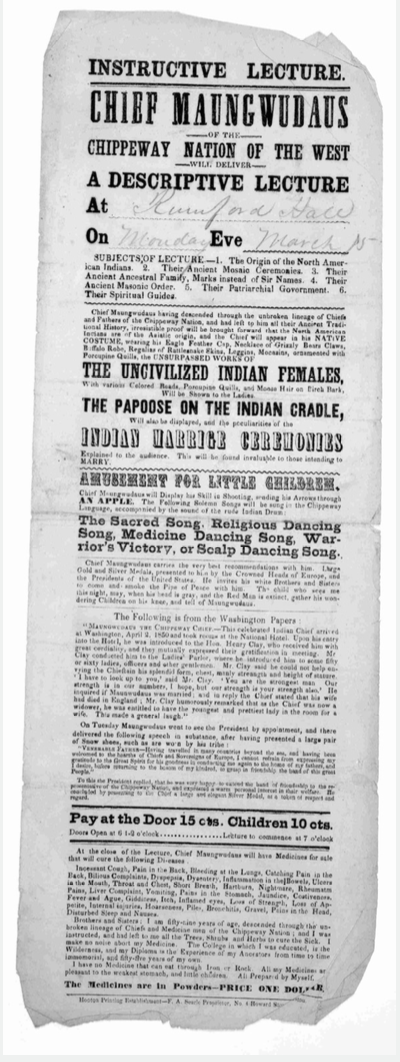

The term “illustrated lecture” appeared later than one might have assumed—at least later than I had assumed. One of the earliest uses of the term came in the summer of 1841—a news item in the Manchester Guardian on a demonstration of the Electromagnetic Printing Telegraph at the Royal Polytechnic Institution—it was widely reprinted in the American press.{10} At first the similar term “illustrative lecture” appeared in newspapers with at least equal frequency. It was not until the 1850s that the familiar term achieved wide currency. Maungwudaus, a chief of the Chippewa Nation, certainly contributed to the codification of illustrated lecture as a terminological signifier. He began to tour the United States with his family in late 1848, giving lectures that were illustrated by appropriate dances, the indigenous methods of nursing babies, a scalping scene, a council of peace, and shooting at targets with bows and arrows and a blowgun.{11} They were promoted as a corrective to earlier representations of a similar kind. By 1851, the entertainer was advertising his program as an illustrated lecture and did so consistently for the next four years.{12}

Chief Maungwudaus and his troupe Chippewa Indians c. 1846, daguerreotype.

Chief Maungwudaus and his troupe Chippewa Indians c. 1846, daguerreotype.

JG

These illustrated lectures appear removed from what we generally think of as documentary—even compared to the illustrated lectures of Stoddard and Holmes which involved both projection and photographic images. While the printing press played a crucial role in advertising and circulating information about these performances, the lectures nonetheless lacked elements of technological reproducibility or mediation in a Benjaminian sense. Without a kind of reliance on “optical proof” in the form of visual illustrations, was there an alternative conception of “documentary truth” that was communicated to audiences?

CM

Precisely. We need to ask: what did the documentary tradition look like before the age of technological reproducibility (or reproducibility outside that of the printing press and lithography)? Did documentary’s longue durée necessarily depend on the photographic image or on projection? Is technological mediation of some kind necessity? No, I conclude. Maungwudaus’s troupe of performers were not acting—or claimed not to be acting—in the sense of playing roles; they claimed to be putting their “authentic” or true selves on display. Nevertheless, it is fascinating and significant that the emergence of photography and the emergence of the term “illustrated lecture” roughly coincided. The 1840s was surely a decade when the documentary impulse à la Stott flourished in American and European culture. Edgar Allan Poe’s essays on photography in 1840 raised the issue of truth in photography from two different perspectives that have bedeviled documentary studies to this day. The first has been a curse to documentary studies—that the image or representation can offer absolute truth through a perfect correspondence to nature. The other, largely ignored, is more helpful: the photographic image is more truthful in relation to the painted image. Truth is relative and comparative.

Advertisement for an instructive lecture by Chief Maungwudaus of the Chippeway Nation of the West.

Advertisement for an instructive lecture by Chief Maungwudaus of the Chippeway Nation of the West.

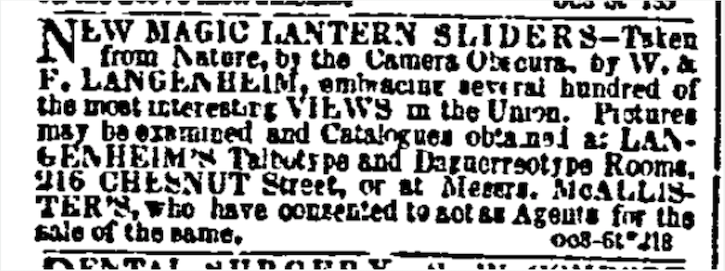

In any case, the Langenheim Brothers—Frederick and William—produced a key technological innovation so far as a more modern and perhaps recognizable version of the documentary tradition is concerned. In 1849 they developed the albumen process by transferring photographic images to glass plates. In fact, these transparent images had a variety of possible uses but one of the most important was their use as lantern slides, which the Langenheims showed at the 1851 London Crystal Palace Exhibition. What is striking here is that the descriptives or associated terms which commentators deployed for the illustrated lecture and for the projected photographic image were strikingly similar. Photographic lantern slides were said to offer “greater accuracy of the smallest detail … drawn and fixed on glass from nature, with a fidelity truly astonishing.”{13} Moreover, “the representation is nature itself….omitting all defects and incorrectness in the drawing which can never be avoided in painting a picture on the small scale required for the old slides.” Likewise, Maugwudaus’s presentations involved “an accurate picture of real INDIAN LIFE” and were “on an extensive scale and in a most comprehensive manner.”{14} They claimed to be more accurate than similar presentations that had been given by white men—or even other First Peoples.

The Langenheims thought of themselves as photographers rather than lecturers—even illustrated lecturers. Their early presentations offered a novelty of precision and truth—an instance of scientific innovation. We might even think of them as offering a series of “attractions” to appropriate Tom Gunning’s term.{15} Theirs was an important technological innovation, but if we take Phil Rosen’s idea of documentary involving a level of complexity, delay, and synthesis, they would likely fall short. In any case, if newspaper searches are any indication, their kind of presentation did not break through a critical threshold in terms of audiences.{16} Their “hyalotype” seems to have been understood as an innovation in photography rather than contributing to a transformation of screen practices. In the United States at least, the moment when photography had a broad-based cultural impact on nonfiction screen programming seemingly came a decade later with the introduction of the “stereopticon.”

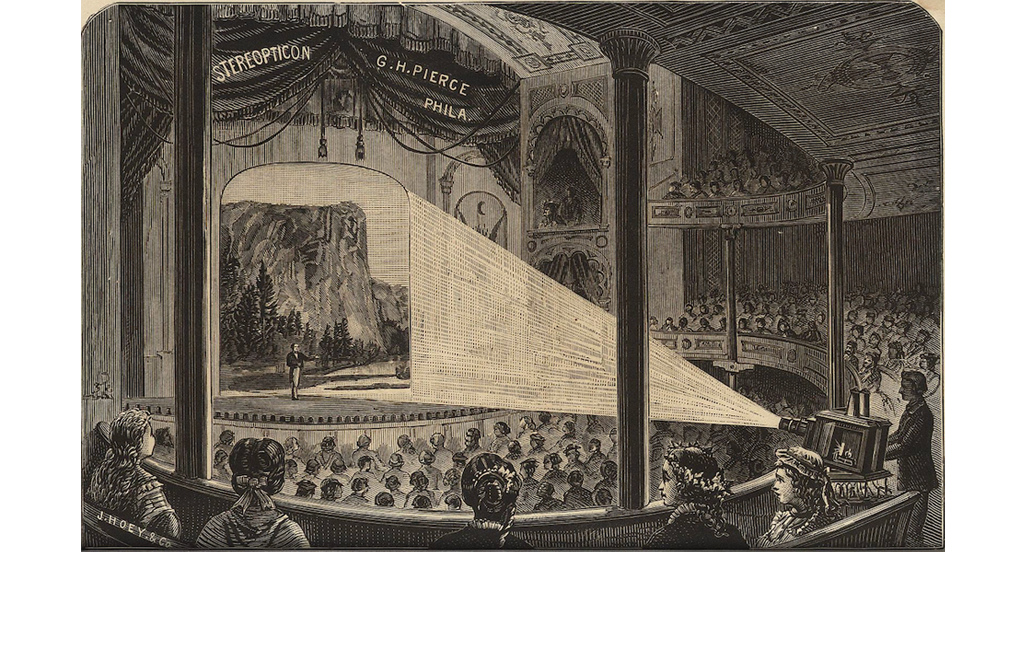

The stereopticon was a popular term that gained currency in late 1860; it was used to describe the newly up-to-date magic lantern. To provide some historical perspective or a genealogy of terms: in the United States the magic lantern was superseded by the stereopticon (sometimes referred to as the “optical lantern” in England), while the term stereopticon was eventually supplanted by the term “slide projector” beginning in the 1920s. {17} The term “stereopticon” contained within it three different, overlapping meanings. First, the stereopticon was the name for a specific type of apparatus that was invented by John Fallon of Lawrence, Massachusetts, but was then quickly applied to similar devices. Second, it was the name for what many considered a new media form not unlike the introduction of the motion picture projector that launched the cinema. Finally, given its repertoire of photographic images, the stereopticon launched even as it named a mode of nonfiction screen programming. Its appearance was a crucial moment in the documentary tradition, even though—and this is important—it was not immediately deployed in the service of the illustrated lecture.

Advertisement for Magic Lantern Slides (then known as sliders), PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC LEDGER, 10 October 1850.

Advertisement for Magic Lantern Slides (then known as sliders), PHILADELPHIA PUBLIC LEDGER, 10 October 1850.

Unlike the Langenheims, Fallon turned over the exploitation of his invention to his associate Thomas Leyland and theater manager Peter E. Abel, who were not involved in either image making or the construction of apparatuses. As full-time exhibitors, they gave the stereopticon its commercial debut in Philadelphia on December 22, 1860—just as the Civil War was getting started. At first their programs featured travel views; for instance, patrons might tour the great capitals of Europe. Soon they and other exhibitors were also offering sustained accounts of the Civil War—obviously from a pro-Union point of view.

JG

People often think of the stereopticon as a variant name for the stereoscope. Why this confusion?

CM

Well, the stereopticon was a catchy neologism that lacked copyright or trademark protection. Even in the 1860s, the name was occasionally slapped on apparatuses related to the stereoscope.{18} Certainly the term “stereopticon” is derived from the stereoscope and the very idea of stereoscopic views. The viewer used a stereoscope device to look at a pair of stereoscopically related images of a scene in such a way as to produce the impression of a single three-dimensional image. After 1850, these were usually photographic views that were taken by two parallax cameras. When it came to the projection of a single photographic slide, commentators acknowledged that the image could give a much stronger sense of depth than a small photograph or certainly a painting: therefore, the projected stereopticon image was said to often offer a “stereoscopic effect.” But there was a second, perhaps related reason for the name similarity. The best photographic views for the stereoscope were on glass. These double views which were almost identical, could be cut in half and sold as lantern slides. Many photographic images were made both for the stereoscope and the stereopticon, depending on the desires of the customer. One was for private, domestic use; the other for group, public viewing. They complemented each other. The Stereopticon was a big success in Philadelphia, and Leyland and Abel toured many cities on the East Coast even as competitors began to sell and/or exhibit their own versions of the stereopticon.

The stereopticon as a vehicle for nonfiction programs was explicitly opposed to the phantasmagoria and the old-fashion magic lantern that showed painted or lithographic slides often of a fictive, fantastic, or magical quality. The stereopticon was educational, based in science, and embraced what Bill Nichols refers to as the “discourse of sobriety.” Although these nonfiction programs were consistently advertised as “The Stereopticon,” the term’s multiple meanings created problems. The stereopticon qua apparatus could be used to show all sorts of slides—including painted slides or slides generated from painted works, like in the style of Joseph Boggs Beale.{19} It could also easily be used to show comic slides and the like. Moreover, from 1870 onward, exhibitors used the stereopticon for outdoor advertising purposes, which involved a miscellaneous collection of views. In short, the term soon lost much of its initial specificity so far as nonfiction programming was concerned.

JG

So once again you have a crisis in terminology.

CM

So it would seem. The subsequent process of incorporating the term “stereopticon” into the documentary tradition was complex and reminds us how fluid language can be. Let’s step back for a moment. Nineteenth-century America seemed to emphasize three different modes of presentation. There was public speaking, which included the sermon, the lecture, and political oratory. Here the spoken word was paramount. Although a lecture could be illustrated, the illustrations were subservient to the verbal—experiments confirmed or illustrated the scientific assertion. There were also exhibitions—where paintings and other art works were exhibited. There was also the 1851 London Crystal Palace Exhibition (as mentioned above) where objects might be presented with verbal or written explanations, but these descriptives were always in a secondary role. Finally, there were performances—most commonly circus performers and actors playing roles in the theater. As they had done for hand-painted lantern slides, often known as dissolving views, newspaper notices consistently referred to the stereopticon as being exhibited—or as the featured element of an exhibition.{20} A substantial review of a stereopticon show from early 1861 called the show an “entertainment” four times and employed variants of “exhibit” and “exhibition” a total of seven times. The term “lecture” was never mentioned. The focus was on the “Stereoscopic Photographic Pictures” and the “extraordinary dimensions” of the image.{21}

JG

How then did these nonfiction educational programs come to be called “illustrated lectures?”

CM

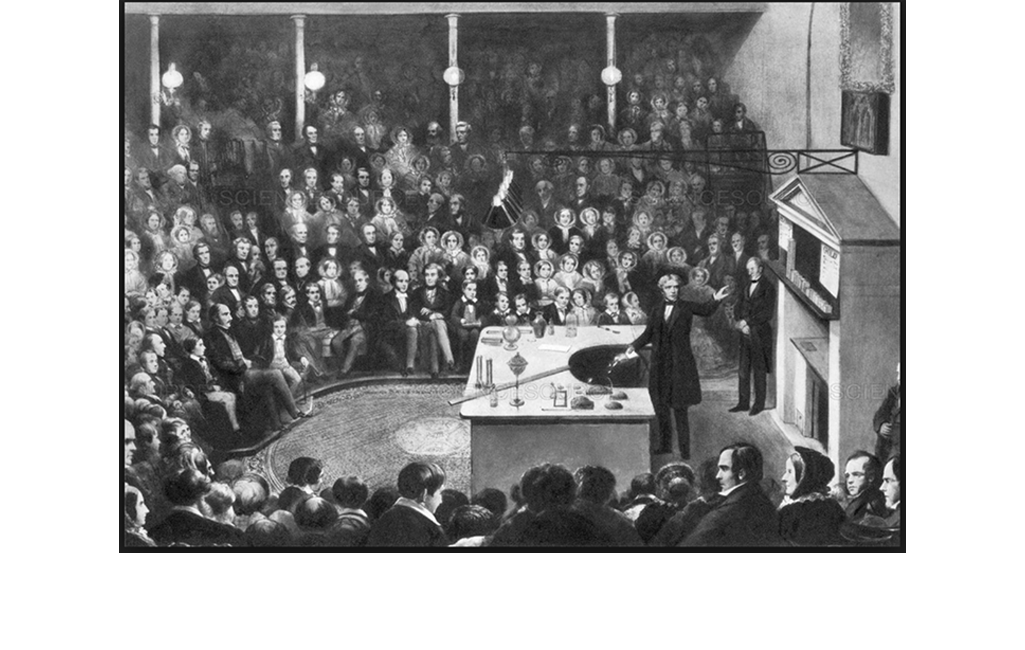

You had two competing types of presentations that offered complementary assertions of truth value: the lecture which offered reason, science, and secular culture (music, literature, art, history and so forth) as the basis for enlightenment rather than religion, and the stereopticon exhibition that offered the truth of the photographic image in contrast to previous types of image making (i.e. painting). Nevertheless, stereopticon exhibitions did generally have a verbal accompaniment, typically performed by a “delineator” rather than a lecturer. With the power and immediacy of the projected photographs considered the essential aspect of these stereopticon entertainments, the subject and quality of the images were routinely promoted—while the commentator typically remained anonymous and unacknowledged.

These two strands gradually came together. It may be significant that the stereopticon suffered a serious dip in popularity in the immediate post-Civil War era. Given a seemingly endless repetition in similar kinds of subject matter, stereopticon programs lost some of their power. Renewal began around 1870 with some subtle but significant shifts. New topics or genres began to appear and this gradually led to a new configuration of otherwise familiar terms. Programs on Yosemite Valley and then Yellowstone National Park became extremely popular. Photographer T. Clarkson Taylor travelled to Yosemite in the summer of 1869 and that December he gave a “stereopticon exhibition” on California and the Yosemite Valley in Philadelphia. The advertisement for his evening entertainments clearly emphasized the photographs—the term “lecture” was not used: his programs were “illustrated with beautiful Illuminated Photographs.”{22} Significantly the photographer himself was presenting the views—he was exhibitor as well as cameraman, in charge of both production and post-production. In short, he was the clear author of his program—which had not been the case with earlier stereopticon exhibitions offered by Leyland and many others. The following month Taylor exhibited in Manhattan and Brooklyn, delivering two “lectures.” The second was entitled The Yosemite Valley: “They were “illustrated by forty photographic views taken by himself during the past summer, and magnified by the Stereopticon.”{23} Since he had obviously been to Yosemite, Taylor’s comments had a privileged status—the perfect complement to the images. It was not a question of exhibition or lecture but exhibition and lecture. Photographic lantern slides were proving to be a more flexible and cost-efficient way to present illustrated lectures. Dr. John Boynton was also representative of this shift. He toured the Northeast giving a series of “scientific lectures” or illustrated lectures on geology and kindred sciences in the 1850s and early 1860s.{24} These were illustrated by eighteen large paintings covering more than 3,000 feet of canvas.{25} A decade later he was still giving illustrated lectures, but now photographic lantern slides provided the illustrations. The adoption of lantern slides for illustrated lectures was gradual and never universal; however, by the 1880s the association of one with the other was well established. These newly defined illustrated lectures combined both exhibition and lecture, sound and image, in a way that suggests a fully developed nonfiction audio-visual formation. We might say that documentary’s initial truth value (science and reason versus religious dogma) was now buttressed by related truth claims in representation (the accuracy of photography over painting). With this conjunction one might argue that the documentary tradition entered the modern era.

Nonfiction screen practices were vital, dynamic, and rapidly expanding in subject matter and approach throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century. By late 1872, E & H.T. Anthony & Co. was selling “Photographs of celebrated Oil Paintings, beautifully Colored.”{26} As this would suggest, illustrated lectures on art and artists were becoming popular. Rev Henry G. Spaulding, for instance, offered a course of six illustrated lectures on Roman Life and Greek Art in Ancient Pompeii using a powerful stereopticon.{27} Historical programming also found appreciative audiences. Illustrated lectures on Napoleon were particularly popular. Those on the American Civil War, which had been commonplace during the war itself, reappeared and flourished from the mid-1880s well into the next century. Jacob Riis unveiled his pioneering social issue program The Other Half—How it Lives and Dies in New York early in 1888. Later that year, John Wheeler introduced The Tariff Illustrated, a pro-Republican full-length program that was the progenitor of the campaign documentary. Travel remained popular but lecturers often delivered programs on more distant lands: Africa, Asia and the Arctic.

These programs also offered a range of representation approaches. Some illustrated lectures used the “voice of God” approach—particularly common among preachers who often worked from pre-scripted, packaged lantern programs on a variety of subjects—adapting them to their own tastes and the expectations of their audiences. Their authority rarely came from personal encounters with their subject but depended on their rhetorical skills and standing in the community. In contrast, preeminent lecturers like John Stoddard, who was active between 1880 and 1896, and his protégé E. Burton Holmes, brought photographers along on their travels. They not only stood by the screen and offered commentary about their journeys, they also appeared in the photographs shown on screen, providing their illustrated lectures with first-person, subjective accounts on an array of important topics involving the environment, war, international expositions, and a cultural understanding of foreign cultures. These lecturers were auteurs in every sense of the term,developing an array of representational strategies that would be revived in a more contemporary form by documentary filmmakers like Ross McElwee, Michael Moore, Judith Helfand, and Marlon Riggs.

JG

Most people attending a lecture today wouldn’t call what they were witnessing a “documentary.” But nineteenth-century screen practice not only inflects late twentieth and twenty-first century personal documentary, as you mention, but the mainstream filmmaking endeavors of figures such as Ken Burns as well as his circle of peers and collaborators (Ric Burns, Stephen Ives, Diane Gary, Lawrence Hott). Likewise, the illustrated lecture was given a twenty-first century cinematic reboot with films such as An Inconvenient Truth (2006). In more recent years, illustrated lectures have made their way into the increasingly popular sub-genre of the “social campaign documentary,” which features the accessible explication of a pressing issue (often from a moderate-liberal perspective and with celebrity voice-over). Can you speak about the persistence of the illustrated lecture and how this “longer view” of documentary might enrich our study of it today?

CM

The documentary tradition has a long and rich history: in the last decades of the nineteen centuries many of its essential genres, tropes, and techniques were firmly established. Documentaries on national parks such as The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009), the six-episode series produced by Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan, are direct descendants of those stereopticon exhibitions and illustrated lectures on Yosemite and Yellowstone National Park. Moreover, numerous treatments of this topic (the national parks) were made in the intervening hundred and fifty years. Much the same can be said for other genres on subjects such as war, urban life, art, travel and more. The long view can give us new insights into documentary’s more recent past—even as contemporary practices enable new perspectives on these past efforts. Although new media technologies were constantly allowing for, if not necessitating, the reinvention of nonfiction audio-visual productions; there were important, fundamental continuities as well, including the relationship between practitioners and their subjects. This longue durée enables, indeed requires, the exploration of a wide range of issues—networks of exploitation, ideological struggles and so forth—within a much more extended time frame. We can see more clearly the ways in which changes in media technologies at certain points led to the renaming of a constantly changing, evolving practice that had a richness, depth, and strength that should not be minimized.

Such an approach necessarily changes the way we think of documentary history in relationship to the history of cinema. Following this logic, the documentary tradition should not be seen as a subset of the history of cinema—but something else. They are two perhaps incommensurate histories that intersect, overlap, and become intertwined. Documentary practices offered a method of communication that incorporated new media forms as they became available. Projected celluloid-based motion pictures was but one of these. Admittedly this is a quick and abbreviated sketch, but it anchors what we as documentary filmmakers do as cultural practitioners within a much longer, rich historical trajectory. It also suggests a somewhat new and intriguing answer to the question: what do documentaries do? As documentary filmmakers, we seek to enlighten our audiences—shed light on a subject, a problem or an experience—however much our efforts may sometimes fall short.

{1} For recent monographs on documentary and emerging media, see, Patricia Zimmermann and Helen De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2017), Kate Nash, Craig Hight, and Catherine Summerhayes, eds., New Documentary Ecologies: Emerging Platforms, Practices and Discourses (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); and Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose, eds., i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (New York: Wallflower Press, 2017). For recent studies on the politics of documentary practice, see Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Maria Guadalupe Arenillas and Michael J. Lazzara, eds., Latin American Documentary Film in the New Millennium (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); and Kuei-fen Chiu and Yingjin Zhang, New Chinese-Language Documentaries: Ethics, Subject and Place (New York: Routledge, 2015). For overview collections of contemporary documentary case studies, see Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow, A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015); and Brian Winston, Gail Vanstone, and Wang Chi, eds., The Act of Documenting: Documentary Film in the 21st Century (London: Bloomsbury Academia, 2017). For documentary across media and disciplines, see Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, eds., Documentary Across Disciplines (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016).

{2} Recent projects have been insightfully examined the role of documentary in nation-building efforts in post-revolutionary Soviet Union and Cuba, the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the U.S., and social identity formation in colonial and post-colonial India. See Chris Robé, Breaking the Spell: A History of Anarchist Filmmakers, Videotape Guerrillas, and Digital Ninjas (New York, PM Press, 2017); Sara Blair, Joseph B. Entin, and Franny Nudelman Remaking Reality: U.S. Documentary Culture After 1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Guilia Battaglia, Documentary Film in India: An Anthropological History (New York: Routledge, 2017); Joshua Malitsky, Post-Revolution Nonfiction Film: Building the Soviet and Cuban Nations (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013); Thomas Waugh, Activist Documentary at the National Film Board of Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010); and Thomas Waugh, The Conscience of Cinema: The Works of Jorvis Ivens, 1912-1989 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).

{3} See, for example, Jonathan Kahana, ed., The Documentary Film Reader: History, Theory, Criticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

{4} Charles Musser, “Problems in Historiography: The Documentary Tradition Before Nanook of the North,” in The Documentary Film Book, ed. Brian Winston (London: British Film Institute, 2013). Just to say that this essay suffers from many of the theoretical problems we are seeking to address here.

{5} See the chapters “A Range of Documentary Inquiry” and “Epilogue: ‘Documentary Studies'” in Robert Coles, Doing Documentary Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997); and A. William Bluem, Documentary in American Television: Form, Function, Method (New York: Hastings, 1972).

{6} “New York,” New York Weekly Journal 24 (October 1743), 3; I.

Bernard Cohen, Benjamin Franklin’s Science (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1990), 40-60.

{7} Advertisement, New York Gazette, July 22, 1751, 3.

{8} Advertisement, National Gazette and Literary Register (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 4, 1826, 2.

{9} Anon., “St Eustatia Prize Bill,” London Chronicle, July 4, 1789, 23; “House of Lords,” April 12, 1788, 359; Anon., “Account of the Trial of Warren Hastings, Esq.,” American Magazine, July 1788, 516; Anon., “Sketch of Mr Hasting’s Trial,” Connecticut Courant, August 22, 1791, 2.

{10} “The Electro-magnetic Printing Telegraph,” Manchester Guardian, (Worcester, Massachusetts), October 20, 1841, 1.

{11} Ibid.

{12} Advertisement, Cleveland Daily Herald, July 8, 1851, 2; advertisement, American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, May 15, 1852, 3; advertisement, Newark Daily Advertiser, October 8, 1855, 3.

{13} The Langenheims, as quoted in The Art-Journal (London) April 1851, 106.

{14} Cleveland Daily Herald, July 8, 1851, 2.

{15} Tom Gunning, “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde,” Wide Angle 8, nos. 3-4, 1986.

{16} Phillip Rosen, “Document and Documentary: On the Persistence of Historical Concepts,” in Change Mummified: Cinema, Historicity, Theory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

{17} The stereopticon brought together three new elements: 1) the photographic lantern slide which had undoubtedly undergone further refinement since the Langenheims’ breakthrough so that it had become easier and quicker to produce these lantern slides (the substitution of the collodion process for the albumen process is but one factor in such refinements); 2) the introduction of a much stronger light source, typically oxy-hydro or calcium light, which allowed for a bigger and brighter image; and 3) much sharper, high-quality lenses that allowed for a superior image projected on the screen (recall the difference between VHS video and HD Blu-ray).

{18} Rawson’s stereopticon was a variant of the stereoscope viewer. (“Rawson’s Stereopticon or Stereoscope and Case Combined,” Philadelphia Photographer, July 1, 1897, 43.

{19} Terry and Deborah Borton, Before the Movies: American Magic Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale (Bloomington, IN: John Libbey Publishing, 2015).

{20} “Amusements,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 19, 1860, 8; “Amusements,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 4, 1861, 8; “Amusements,” Dollar Newspaper, October 26, 1861; “Amusements, Music, etc.,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 1861, 5.

{21} “Amusements, Music, etc.,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 1861, 5.

{22} Advertisement, Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, December 4, 1869, 2.

{23} “Lectures,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 26, 1870, 1. Taylor, who ran a school in Wilmington, Delaware and had given illustrated lectures using the stereopticon, died on October 25, 1871. (“Scientific Lectures,” Delaware Republican, February 5, 1866, 2; “Died,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 27, 1871, 5.

{24} Advertisement, New York Herald, February 26, 1852, 5.

{25} Advertisement, Hartford Courant, December 9, 1853, 2.

{26} Advertisement, New York Commercial Advertiser, December 21, 1872, 2.

{27} Advertisement, Brooklyn Eagle, January 12, 1879, 1.