Camera Ministry: A Conversation with Khalik Allah

Emily Vey Duke, Cooper Battersby & Vashon Watson

When we brought Khalik Allah to speak to our students at Syracuse University last spring, he was enthusiastic about everything, and brought with him several pairs of spotless sneakers. He had boundless patience and solicitude for our students, who adored him and hung on his every word.

He came to show his formally inventive and emotionally harrowing documentary Field Niggas (2015). We had sought it out on YouTube after reading about it in an online experimental film forum, where it was described with the kind of hushed reverence usually reserved for flickering abstraction.

Field Niggas is a 60-minute documentary in which glowing, brilliantly colored faces float across the screen in slow motion. The subjects are the denizens of 125th and Lexington, a storied corner in Harlem. They are largely disenfranchised, mostly addicts, exhaling clouds of K2 or Spice, the “synthetic marijuana” also known as bath salts. Khalik turns his lens on them in love, inviting viewers to see them with love too.

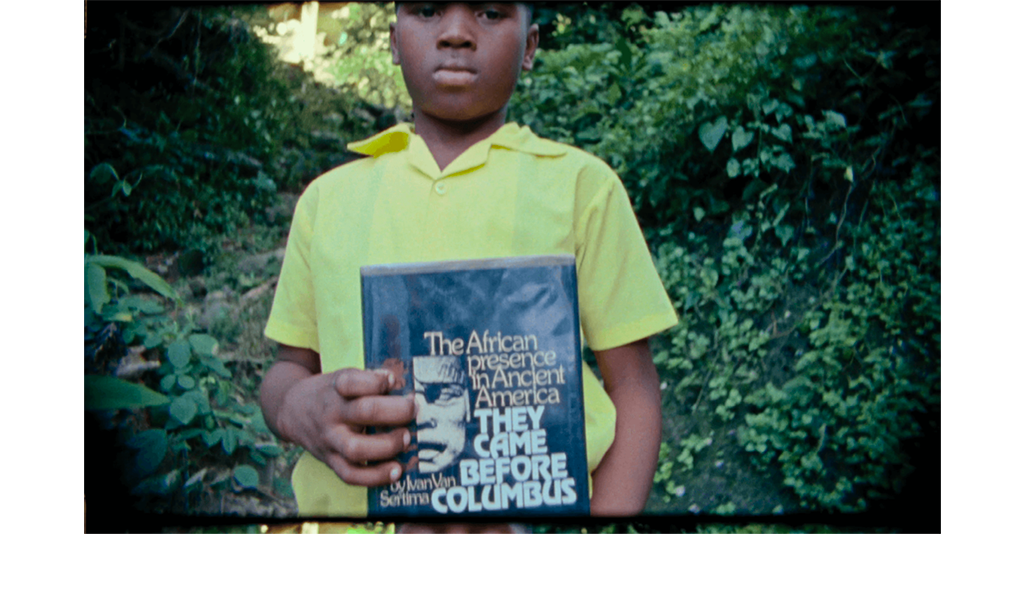

Khalik grew up on Long Island. He was held back a year in middle school because he was skipping classes to breakdance and study at the Harlem headquarters of the Five-Percent Nation, a group founded in 1964 by a former student of Malcolm X. The Five Percenters teach that the Black man is God personified, and that members of the Nation have a responsibility to bring light to the rest of the world. It’s a group that places tremendous value on scholarship, and Khalik was drawn to it by interest in “discipline, self application, (and) a recognition of internal power and a responsibility to educate one’s self.”

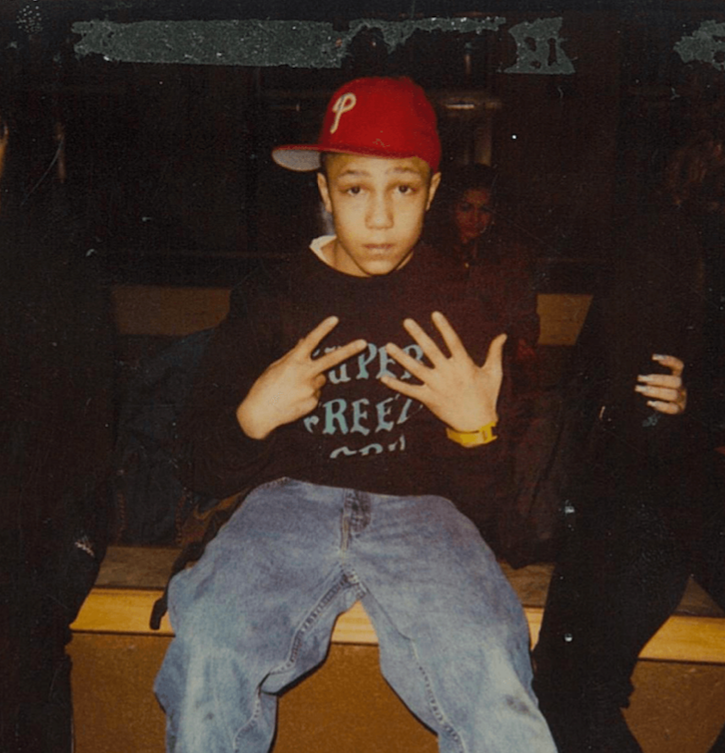

“Twelve years old in the club with my Bboy crew.” Courtesy of Khalik Allah.

“Twelve years old in the club with my Bboy crew.” Courtesy of Khalik Allah.

At nineteen, he began an influential relationship with several members of the Wu-Tang clan. In 2008, Khalik was the tour cinematographer for GZA, a notable member of the group.

His work has been screened prodigiously these past few years, winning awards at Pulse Films, Brit Doc, Sarasota Film Festival, Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire de Montreal, and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, among others. October, 2017, saw the publication of his book Souls Against the Concrete, published by University of Texas Press.

Now he is deep in the process of making his next film, Black Mother, shot in Jamaica, where his maternal grandfather lived and died. While Field Niggas was made entirely outside of the independent documentary industry, he is making his new film as part of the Sundance Art of Non-Fiction Fellowship, along with fellow creators Kitty Green (Casting JonBenet), RaMell Ross (Hale County, This Morning, This Evening), Brett Story (The Prison in Twelve Landscapes), and Kirsten Johnson (Cameraperson).

We interview him here with Vashon Watson, an emerging filmmaker and musician who splits his time between Syracuse and the Bronx.

****

Interview

Cooper Battersby

We’ve got Vashon Watson with us, one of our students. You met him last spring when you were here in Syracuse.

Khalik Allah

Yeah I remember him. What’s up, Vashon?

Vashon Watson

Hey, how you doing? Nice hearing from you again.

KA

Doing well, bro. Yo, I remember, man.

VW

Um, do you though? Are you sure you remember me?

KA

Yeah, you were quiet. I remember everybody.

VW

Yeah, that’s me. I’m that guy. (laughs)

CB

So what are you doing right now?

KA

I’ve been hibernating this past couple of months, just trying to edit this film.

Emily Vey Duke

Black Mother? That film?

KA

Yeah, definitely. It’s coming together. I’ve been doing a fellowship with Sundance for documentaries that are exploring more unusual approaches to filmmaking. You know, kind of what like Field Niggas was.

CB

One of the things that I’m interested in hearing more about is your concept of the Camera Ministry. It makes this claim which is so unusual for documentary: “that the subject of the documentary is benefitted immediately,” rather than in some kind of “the viewer will see it, and then maybe it’ll improve the life circumstances of the subject” way.

KA

Right. Well, whether it’s photography or filmmaking, it was always about me wanting some sort of therapy in the shooting. The first job that I had, while I was making Field Niggas on 125th (Street in Harlem), was in a place that was really limiting on my creativity. I was basically a control operator. I was just watching commercials every day, making sure that they were playing properly. I was inundated with so much material, and I was desiring just to get back to my element, you know, to be around people that are struggling, that reflect more how I came up, as opposed to all the stuff I was seeing at my job.

So first it was a therapy for me just to go out shooting. I wasn’t really speaking to people more than “Can I take a photograph.” But then it became something deeper, where I started to see that, yeah, this is helping me out, I’m getting to reconnect with a part of myself that I just felt like I was disconnected from.

And then it took on another turn, after I kind of got what I wanted, which was just that feeling back, of being in the streets. And I started just to recognize how much help people really needed. What I was able to give people at that time was attention. And that became an exchange.

So I may ask somebody “Can I take your portrait?”, And they may say “why”, and that may go into a discussion that lasts a while. And I always came with the level of “Yo, you may be struggling now, but you could change, or things could change in your life.” And that’s when I began to call it Camera Ministry.

The actual trigger which made me think about that was the light itself. (I was) shooting at night time, being forced to use whatever little light I can—a lamppost, a storefront, whatever—the light pouring out the windows. And just telling people “Walk with me into the light.” And after saying this so many times it just clicked in my head that that is a metaphysical statement.

So I began what I was doing like I was on a mission, I kind of felt like De Niro in Taxi Driver.

Excerpt: FIELD NIGGAS, Khalik Allah (2015).

VW

Just hearing you talk I was just having so many thoughts. And when you were here last year I had questions I didn’t ask you…

KA

Ask them, brother. Feel free.

VW

How effective do you think your film Field Niggas would have been if your audience was only people from the hood?

KA

Effective in what sense? You mean making them stop using drugs?

VW

No, not making them stop using drugs. I feel like you were exposing them to an audience that wasn’t primarily Black. The content was exposing how the hood actually is, and what actually goes on there. So how do you think that film would be received by the people who are doing drugs, or are actually living in those neighborhoods.

KA

Well they’ve seen it. The people on 125th have seen the film. Most of the people that are in the film have seen it. I’ve gotten that question before, because, when you make a film called Field Niggas dealing with people in the hood, you’re walking that line whether it’s exploitation or not. You know? I’ve been to screenings where the audience has been a hundred percent Black. And I’ve been to screenings where the audience is a hundred percent white. And usually I get the same questions. And usually people laugh at the same time if they laugh at all. And usually people have a similar response. You know?

And I really like showing it to white people anyhow. Because I want them to understand the suffering. You know? Right now, the reason why white privilege is the way it is is because there’s a lack of understanding as to Black under-privilege.

Sometimes white audiences have said to me “I didn’t know that these people had that much character. Had that much depth.” And that’s a little unfortunate, that people might think that people don’t have character based off living in the street. But if I was able to change their mind I’m happy about that.

EVD

I think part of Vashon’s question is—do you think that art audiences that are so largely white have responded so well because they think the subjects are exotic?

KA

Well, perhaps that may be true. People fear what they don’t understand, and a Black hood has always been feared. It’s an illusion though. Black people are criminalized, but many are really in a powerless position in the hood. Many are really financially suffering, nutritionally suffering.

CB

I see your work as having two goals, the first one is your immediate relationship to the people who are right in front of the camera with you, through camera ministry. The second one is your desire to make some sort of document of the encounter that will be interesting to the other people, that are going to see your films later on. Are those goals ever in conflict? How do those goals interfere with each other?

KA

Good question. I feel like all of us in our essence are innocent regardless of whatever we think we did to make us guilty. This goes for people that are drug addicts, people who are living on the street, who just got out of prison and can’t get a job. What I’m trying to do is go beneath the surface with my work and use empathy to get deeper access. To me that’s what camera ministry really is.

So I don’t think that the things are in conflict at all. I’m looking at everybody like God, like everybody is God ‘cause I’m seeing God within then. I can’t divorce my spiritual practice from what I do, and part of my understanding is that this life is an illusion and in that we’re dreaming, and therefore we have dream roles. We’re playing the roles of different characters and sometimes the script that we write is a fucked up script.

Excerpt: FIELD NIGGAS, Khalik Allah (2015).

EVD

Do you have any history with faith based ministry or social work that gave you the skills to work this way? We’re thinking partly about your history with the 5% Nation.

KA

No, I don’t. I grew up in a family that was Baptist Christian. My father coming from Iran, he was a Muslim, but he really wasn’t practicing Islam, and my mother was Jamaican. Jamaica has more churches per square mile than any other country in the world, per the Guinness Book of World Records. But growing up with my grandmother gave me a sense of ministry, a sense of, like, everything is alright. I grew up in a household where I had my grandmother and yet I would be in areas where people didn’t have either of their parents and where everything seems to be really fucked up, so I just felt the need all my life to lift people up in whatever way I could.

EVD

Do you feel like you’re continuing with camera ministry while you’re shooting Black Mother in Jamaica?

KA

Yeah, but also I’m being ministered to in Jamaica, so it’s kind of flipped. In Black Mother there’s prayers throughout the film, and towards the end of the film there’s a prayer delivered to me, and I felt really uplifted and ministered to, but ultimately that’s me creating another work to take out into the world, to release this prayer on the world.

I continued in the tradition that I began in Field Niggas of filming at nighttime on the streets in different hoods in Jamaica. In that process of shooting at nighttime, I had to stop many people, similar to Field Niggas, and some of the people that I stopped were like “Yo, nobody has spoken to me like a man in ten years—nobody has shook my hand.”

But the other part of your question, about the 5% Nation, of course that has a tremendous influence on me. Just growing up within the 5% Nation, and also being a hip-hop head and studying the way that hip-hop is depicted visually, all of that ties into my work of course.

CB

In your film Khamaica (2015), your grandfather says “Thank you for this grandson of mine, that has come to look for me in my old age.” When you went there to make that film, was it one of your first trips to Jamaica?

KA

I’ve got a really tight relationship to Jamaica. I’ve been going back since I was three years old, since 1988. My grandfather lives in the countryside. If you were to look at a map of Jamaica and you put your finger to the direct center of the island, that’s where his home is. He’s passed away now, but in 2011, I recognized that my grandfather, he was ninety-six years old and just for archival purposes, I said I need to document him. So I just went to Jamaica to do that, to document him. I didn’t know what that film was going to be. That film was just a freestyle. Back then I didn’t have any attention so Khamaica went straight to Youtube.

His home was like a monastery. All my life I’ve been able to leave New York and go and spend like a week or two with him and just get to that wisdom and that instruction, to be a better man. To grow up into more righteous living. That’s what he gave me. He was a Baptist Deacon and he was always a great example in my life.

EVD

That still from Black Mother you sent us is so beautiful.

KA

When I’m making a film I’m making it so that I’m satisfied. With any film the director has to give himself the liberty to make a film which people may not like. I set out with Field Niggas, especially with that title, feeling that a lot of people would reject it.

The same thing with Black Mother. It’s got a very heavy Christian vibe. Jamaica is a nucleus of spirituality. It just so happens that Jamaicans were controlled by the British and the British had indoctrinated through Christianity the people who were slaves. Same thing in America, you know, force feeding a religion to people. But the thing is the spirituality is so vital for the people that it doesn’t really matter what their religion is. It doesn’t really matter what the container is.

CB

In your previous work the image has often been in slow motion and there’s been non-sync sound. So it has created this feeling that there is a great distance between the reality of what we are seeing but also this intense closeness created by the audio. It is really quite a powerful experience. Are you going to be using a similar technique in Black Mother?

KA

Aesthetically, yes, its related where you have slow motion, you have a lot of portraiture, and you have this intimacy that I’m trying to achieve. But I’m also trying to take it to some other places. I’ve been using a lot of different formats. Some of it is shot on 16mm film, there’s a lot of super 8 film. I’ve been using digital equipment as well. There’s also more silence. There’s a lot of silence in this film which I’m trying to use in a way that I don’t think it’s been used before. There’s actually a film that I greatly appreciate called Into Great Silence (2005) about these monks in France, Carthusian monks. It’s practically a silent film. I’m getting inspiration from that.

CB

Your distribution model has changed significantly since you were first starting out with Khamaica or Field N–, which both first appeared on YouTube. Has the change in audience and distribution channels that are available to you now changed the work that you’re able to make or the work that you can imagine making.

KA

You know, no matter what I’m making, I like to think of it as if I were to release this thing right onto Facebook or right onto YouTube right now, how would it be received? But also I’m not really trying to consider it too much. That can be a distraction. I had to really get to a quiet place, man, where I could just focus on the details. My work is all about the minutiae, from frame to frame to frame, every snap of audio. What’s being said is very important.

Especially now after I traveled the world with Field Niggas and had no expectation of going to these festivals and going to these schools, so now working on my new project it was like, I don’t know if that’s necessarily gonna happen. I know people are interested in my work, but it also changes the way that this is gonna be distributed because this new project is not going straight onto YouTube and Vimeo. I’m learning more about longevity and deepening my roots within documentary.

You heard what I said earlier I’m not trying to invest too much in worldly things, but you need to have one foot in that dimension at the same time. Otherwise you’ll end up being a sucker.

EVD

The thing is that your voice is incredibly important. People will quickly allow you to be marginalized if you don’t fight your way into the center. I feel that way as a woman too. I want my voice to be heard and you want your voice to be heard. It will be a huge loss if you don’t make sure your work receives the widest audience possible.

KA

Thank you, thank you. Without belittling the work or without asking for unnecessary things. I’ll just take what I need. When it comes down to making a film, I made Field Niggas with hardly any money, this new film I didn’t have a $500,000, $250,000 budget, I had around $120,000, $125,000, which to me is a lot of money. I’m gonna have a colorist, a proper colorist. With this project I’m starting to open up, delegate a little more.

CB

That’s great.

KA

But it definitely gets expensive.

EVD

But it’s great also because that means that you are not only feeding yourself as a creative person, you’re able to pay other people to do creative work that they’re excited about.

KA

Definitely. I’m still assembling my crew. Some of my work is so singular, but it’s mainly been my little brother and my sound guy on this project I worked with two people, on Field Niggas I had my man Josh Fury who is a producer from Canada, up in Calgary, and I also brought the Disciple from Wu-Tang, so it’s a little army.

EVD

Khalik, you need to work with some women!

KA

I know I know I know, I need to work with some more women. I would love to work with more women. There have been some women that I’ve worked with, but in different ways. I showed Hannah Buck an early cut of the film last January and even though she wasn’t working directly on the project. She’s an editor who I respect her very much.

VW

I was just wondering– do you ever struggle with being pretentious in your films? is it like —

KA

No.

VW

Do you have to balance having your philosophy with not pushing your philosophy onto the audience? I’ve also tried to put my philosophy and my ways of thinking inside my films and I have trouble balancing putting my belief system onto people. How do you find that balance?

KA

I don’t put it onto anybody. At the end of the day when the film is done it is out of my hands if somebody is going to consider it pretentious.

That has happened with Field Niggas. 90% (of my write ups) have been positive, but there were a few people that felt that there was too much of an inclusion of the director and the director’s voice, but that’s okay too because you know these films are timestamped. When you look at Field Niggas that’s the summer of 2014. If you go back on that same corner right now it’s a lot different.

When you go into creation you have to have a lot of confidence in what you’re creating. I think that’s what makes Field Niggas what it is. But that confidence also came with the lack of understanding that the film would travel so far. Maybe if I knew it would be seen by so many people I would have curtailed certain elements of myself in the film.

Excerpt: FIELD NIGGAS, Khalik Allah (2015).

EVD

There’s a moment in Khamaica where you ask your grandfather what he thinks about fame, and it’s totally surprising and reveals so much about you as the filmmaker, and he’s got a great answer that basically is what you just said: that fame is in service of the ego, and that it is ultimately going to burn you. But I really love it in Field N– that you appear in the mirror, and that we hear your voice so much.

KA

I felt it was important to work with myself with Field Niggas that way, even my person. To me that was very important, because again flying back to the idea of exploitation, I wanted to be just another character in the film. Why have I been able to tell this story? Because I’m ingrained within this environment.

It’s not just a film–these people know me, we’ve developed real relationships. I’ve helped people get jobs. I’ve driven people home in my car. I’ve been to the hospital. I feel including myself kind of brings enough of that to the top.

CB

In Field N– the subjects’ identities are remarkably fluid because the voices have been disconnected from their bodies, but you of course see them as individuals, and hear their voices as being tied to the specific individuals. What were you hoping to achieve by separating the voices from the bodies, and are you worried that your subjects are going to lose their specificity for the viewer?

KA

The goal is to highlight the truth, not the individual. I’m OK with them losing their specificity. More than anything I was trying to capture an energy, and that energy is not contained by one individual. That was what the film was predicated on: the common energy that they’re all experiencing.

There’s no forced narrative in that film where people’s names come up in text at the bottom of the screen. Once we get past the superficial ego identifications then you start recognizing a person off of what they said and what they said alone. Ultimately it was about showing unity, and part of that is not showing the differences but focusing on the similarities.

Background Video: Field Niggas (Khalik Allah, 2015).