Archival Interventions: Cecilia Aldarondo and Thomas Allen Harris in Conversation

Cecilia Aldarondo & Thomas Allen Harris

If the twentieth century was characterized by a need to archive objects, then we could say that the twenty-first century is characterized by a rather different relationship to materiality, one of ‘waste management.’{1} The acceleration of planned technological obsolescence, global anxieties over toxic substances, and the widespread recycling of personal effects all indicate that ours is an age in which materiality exists along a multi- directional continuum of usage and disposal. Objects fall in and out of favor, and as they do, they find their way into private homes, museums, landfills, shopping malls, and other archives. As Aleida Assmann puts it, institutional archives have a “reverse affinity with rubbish dumps,” such that “archives and rubbish are not merely linked by figurative analogy but also by a common boundary, which can be transgressed by objects in both directions.”{2} Perhaps now is a moment to pay attention to the archive’s back doors and exits, its failures and losses.

If objects are at increased risk of abandonment, then we must ask new questions around the politics and ethics of their care: Who has the power to determine what objects are worthy of preservation? How should such custodianship be defined? Is this work reserved for a specialized class of caregivers (archivists, for example)? How does such institutionalization perpetuate the exclusion of the powerless from historical remembrance, and how can we resist such erasures?

In our respective filmmaking practices, both Thomas Allen Harris and I have concerned ourselves with personal, intimate photographic archives as fertile sites for historical excavation and political intervention. While the camera played a key role in documenting and provoking the last century’s events, its byproducts now generate equally significant practices, ones that are predicated more on performativity than on representation. In what follows, we discuss archival exclusions, rethink the amateur archivist, and propose a model of the artist as irreverent custodian of the material past. — Cecilia Aldarondo

Interview

Cecilia Aldarondo

We’ve both made documentaries animated by amateur archives that have been produced and maintained by people of color. How does the amateur archive figure in your filmmaking?

Thomas Allen Harris

The first time I started working with the archive as a kind of animating force was in my 2001 film E Minha Cara/That’s My Face. I had used bits and pieces of the archive in earlier projects, but with That’s My Face I began to engage in the archive in a structural way, as opposed to using it illustratively. I had gone to Salvador da Bahia, Brazil with two Super 8 cameras looking at my roots by documenting the Afro-Brazilian religious festivals that climaxed in carnaval. My mom had made a similar quest when she took me and my brother to live in East Africa in the 1970’s. In part she went because my grandfather’s dream was always to go to Africa, but he was never able to go. I didn’t have any footage of her journey, so I kept struggling to figure out how to tell a story that seemed to span three generations. Maybe a year and a half into editing the Super 8 material I shot in Brazil, I had a waking dream. I recalled my grandfather screening home movies for us when we were kids. I was aware of his extensive photographic archive—his framed photos decorated the walls of our family homes—but I’d forgotten about his home movies. I flew from San Diego to his basement in the Bronx, where I found over six hours of Super 8 home movies. These films (along with his 10,000 color slides) documented of our family, as we rose from a colored, Negro aesthetic to a Pan-African aesthetic.

The search for my mother’s journey in That’s My Face led me to my stepdad’s own home movie archive, into which I delved when I began researching my 2005 documentary Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela. My stepfather, B. Pule Leinaeng (Lee), was a South African freedom fighter living in exile and joined our family when I was nine years old. Lee had left South Africa in 1960 with eleven other comrades, most of whom went to Cuba, got military training, then returned to engage South Africa militarily. After doing training in East Germany, Lee came to the United States and majored in journalism at Temple University, followed by library studies at NYU and ultimately worked in the United Nations Anti-Apartheid Radio. From all these experiences, he had amassed this amazing archive of his life and the anti-apartheid movement.

My stepdad died in 2000. At his funeral in South Africa, I realized that the stories I had heard about the group leaving South Africa had all these holes in them. All of a sudden, with the discovery of his archives and speaking with the surviving comrades, I was able to fill in the gaps and tell the story of the first wave of exiles who left Bloemfontein, South Africa, and kept the anti-apartheid movement alive for over 30 years.

I decided to take Lee’s archive back to South Africa and use it to recreate his journey on film. I hired young South Africans to join me in this journey, and the film moves between documentary and dramatic recreations. What was amazing was that Lee’s archive, and the film that resulted from it, filled in a gap in the South African consciousness about this first wave of exiles from the Free State, the birthplace of both the ANC and the heart of Apartheid. Through the film, this group of exiles became known and celebrated in South Africa as the Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela.

Although these archives were produced by non-professionals, I don’t feel like the word ‘amateur’ applies to them. Like many people of color, my grandfather and stepfather were keenly aware of documenting and preserving untold stories within a racialized society. They well understood the politics of representation. This line of inquiry led me to deeply engage with the work of artists and scholars like Dr. Deborah Willis, who has spent a lifetime documenting and writing African-American photographers and photography into history. Because I had previously made these personal films mining the archive, Dr. Willis invited me to make a filmic interpretation of her landmark book Reflections in Black: Black Photographers from 1840 to the Present (2000), which became my 2014 film Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of People.

CA

My film Memories of a Penitent Heart (2016) also began from the archive, as it were. I was doing my PhD in Cultural Studies, and writing a dissertation that was concerned with the archive as an ideological construct. I was interested in the way that archives can police history; archives are these entities that are animated by whoever is charged with the safe-keeping of material remains. So I was already thinking about the archive as an idea when my mother called me one day in 2008 as she was cleaning out her garage. She was a pack-rat, and it’d taken years for her to finally tackle her messy garage. In doing so, she found this box full of 8mm films and slides. Knowing I loved film, she offered me a deal: if I put them on DVD for her, I could do whatever I wanted with the originals. I don’t think she had any idea at the time where that gesture would lead.

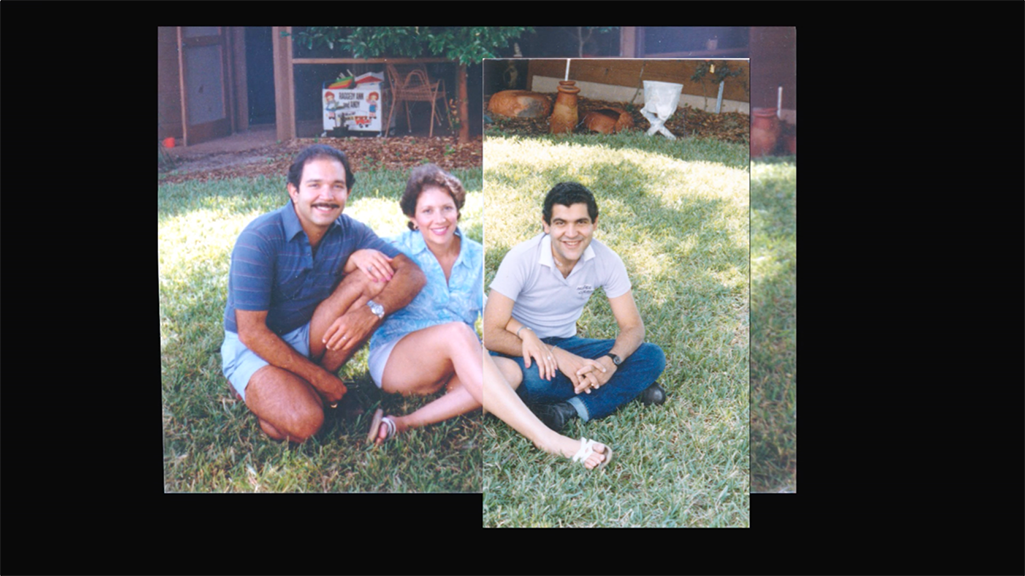

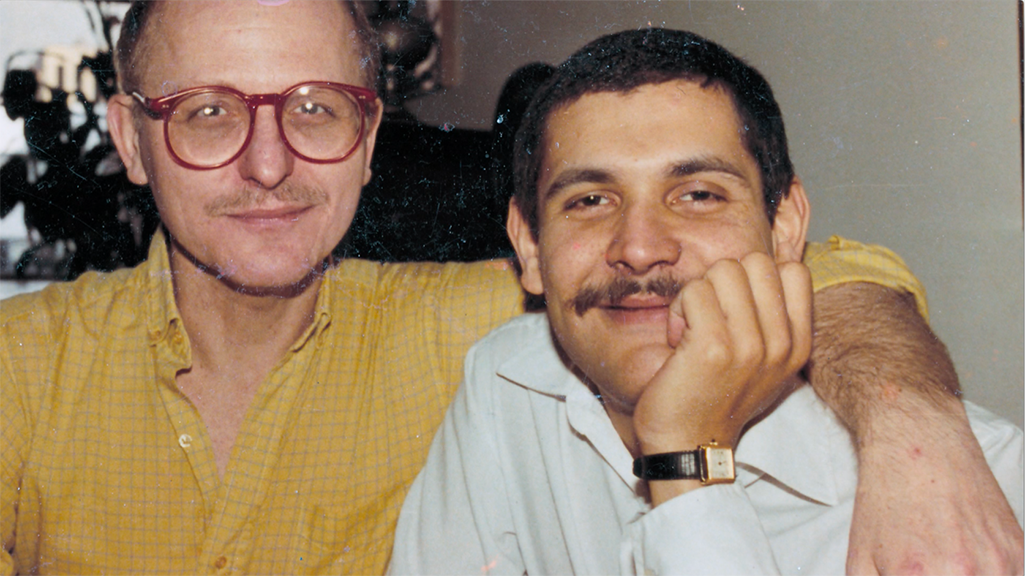

The 8mm films and slides documented my mother’s childhood in Puerto Rico from the 1950’s up until the 1970’s. As I looked through these images, I started remembering stories about my uncle Miguel, who I had only met a couple of times before he died in 1987. The family legend was very cliché in a lot of ways. He was this charismatic actor, his life was tragically cut short at the peak of his artistic talent, he would have made it to Broadway, etc. At the same time, I started thinking about this story that I had heard growing up, the unofficial family history: Miguel was gay and had a partner who disappeared after he died. As I thought about it, this seemingly benign story felt symptomatic of something bigger. Memories of a Penitent Heart began with the discovery of this one shoebox of home movies and photographs. It catalyzed a search, a detective story of sorts.

I think we all sometimes have these origin stories of our films and ‘where it all began.’ In the case of That’s My Face, I think it’s interesting that the archival images that you were seeking were eluding you, at least in the beginning. And in my case, the project began with this archival discovery. I wasn’t just tracking down my uncle’s partner and anyone who might have known him; throughout this search, I was also looking for pieces of another archive.

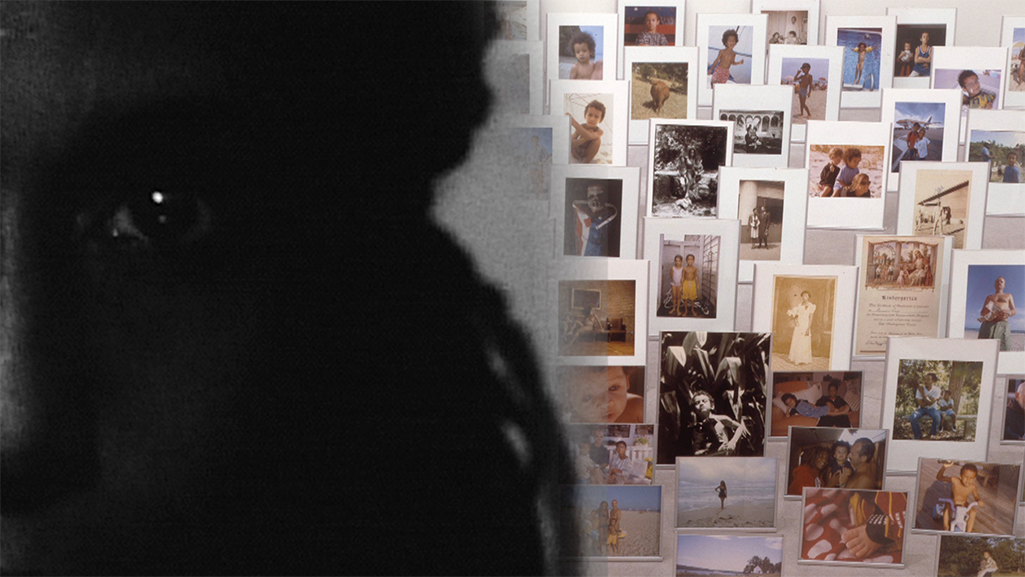

I began with my family archive, with the things that had been kept by three generations of women. My grandmother was the family archivist. She was an inveterate scrapbooker, she was meticulous about hanging on to the stuff of Miguel’s life: his obituary, the prayer card from his funeral, etc. But the more I discovered within this archive, the more it felt terribly incomplete, symptomatic of what was missing from my family memory. I wasn’t finding Miguel, but rather tracing the contours of a terrible emptiness, a memorial black hole where his life as a gay man should have been.

The dominant frame we have for documents is that they are simply evidence of provable facts; documents only matter according to their relative empirical value. But I believe that archival remains are in actuality far slipperier. They can be just as symptomatic of what is missing as what is present, of what has been lost as much as what has been found. Archives are tangled up in memory, rumor, and hearsay: they are staging grounds for speculative histories. In the case of Memories of a Penitent Heart, it often felt like the remains of Miguel’s life were sort of lying in wait for someone to intercede on their behalf. And that someone turned out to be me.

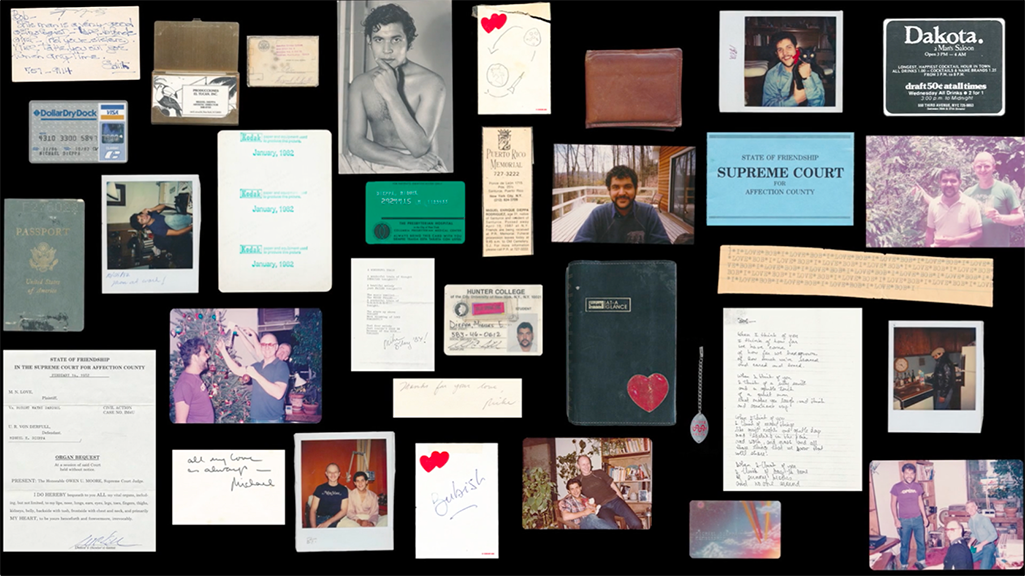

In 2012, after searching unsuccessfully for him for years, I finally met my uncle’s partner Aquin for the first time. At our first meeting he showed me the contents of this cardboard box he had kept in a closet for 25 years. It wasn’t just photographic material: it was my uncle’s wallet, love notes that they’d exchanged, clothing that my uncle had worn. We sat together for three days, working our way from object to object as Aquin told me his version of the story of their relationship. Theirs was a full partnership, to the point where they wore rings and lived together for years; when Miguel got sick, Aquin was his primary caretaker. And yet, as far as my family was concerned, Aquin was little more than a footnote in Miguel’s life. I mean this quite literally: Aquin is completely erased from the family archive. He’s not mentioned in Miguel’s obituary; Miguel’s death certificate euphemistically states that he died of ‘natural causes’ instead of AIDS; my grandmother kept no photos of the two of them.

On one hand, amateur archives can resist official institutional histories that are racist, classist, sexist, and exclusionary. On the other, my family’s amateur archive reproduced the homophobia of the institutional archive. Aquin’s counter-archive—full of photos and love notes between him and Miguel—functions as the repressed excess of my grandmother’s archive, the resistant material that refuses to disappear.

Memories of a Penitent Heart tries to excavate another history, that of Miguel’s non-biological chosen family. But this is a messier task. Often, amateur archives of marginalized people are not properly preserved, maintained, catalogued or tagged. They aren’t kept in cold storage. They are subject to itinerancy and precarious living. In Miguel’s case, my family’s relative social power over Miguel’s chosen community meant that my family archive was relatively intact, whereas Miguel’s gay archive was totally dispersed. It requires a particular kind of activist mentality to go and chase it down and put it together.

TAH

There’s a tendency to replicate institutional assumptions and normalize ignorance along the lines of gender, orientation, or a particular race. But amateur archives like the ones you and I are working with allow us to resist the distorted histories promoted by institutional archives. Case in point: I got a call just a week or two ago by someone who’s doing a project about Super 8. He said, ‘Oh I’m doing this project and I want to include some people of color in it. I know that very, very few people of color engaged in Super 8 home movies, and I think it was because of the expense.’ But actually that’s not true. A lot of the people I know have families that have been shooting home movies on Super 8mm, some dating back to the 1940s in the South.

CA

Why do you think we have this cultural assumption in the United States that people of color don’t document?

TAH

I think that it’s a holdover of segregation. The conventional notion is that people of color haven’t achieved and haven’t created strong institutions. But if you actually look at the archives of people of color, then you start to see black photographers all over the country, you see multi-racial communities, you see women who are pillars of the community and strong hard working men who take pride in their families. You see a variety of different socio-economic narratives. Doing the research for Through A Lens Darkly I saw many examples of black folks who pulled themselves up by our bootstraps, and were already emancipated prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglas documented themselves through photography.

CA

I think that this has to do with deeply rooted assumptions that in a racist culture people of color are always working class. But my family’s home movies document vacations and moments of leisure, everybody dressed impeccably in their Sunday best. These images tell a story about Puerto Rico that is almost never depicted. My family is the product of the mid- 20th-century American colonial project in Puerto Rico, in which the US government forcibly ‘developed’ Puerto Rico from an agrarian society to an industrialized one. This project permeated every aspect of Puerto Rican life, from employment (moving people from subsistence farms to factories and cities), to public health programs (such as the forced sterilization of thousands of women), to mandatory English instruction in schools. Developing a robust middle class was central to this project, and my grandparents were very emblematic of the 1950s American capitalist ideal. My grandfather was the first Puerto Rican to receive his PhD in Psychology. He became the head of the College Board, developed the Spanish SATs, and became this eminent figure in Puerto Rico. And so, when I look through the archive, I see my family enacting a Puerto Rican pantomime of the prototypical, mid-century nuclear American family.

TAH

We see the same in our Super 8 archive. I remember on Easter or other holidays we all went out looking our best, and everything had to stop so that my grandfather could actually capture this particular moment.

CA

In this sense, Super 8 was both the democratized medium that was accessible to a lot of people, and yet it signals a kind of luxury to be able to have access to film stock and developing. It was a leisure hobby in a way.

TAH

Yeah, but I would say that it was a choice. It is a leisure hobby, but there are people I’ve met who range across class and education levels, who made a choice to invest in documenting when they had a little bit of discretionary income. I’m not sure how it shifts in terms of the Puerto Rican landscape, but certainly within the African-American landscape, my grandfather and parents were working class. But they were also educated teachers for whom money was not the first priority. Sometimes community was more important.

CA

I wanted to ask one other question about the role of the amateur archivist, the amateur maker of history, be it through a film, or a book, or whatever might result from the archive. In my case, I come from a long line of amateur archivists. I started this project as an amateur before I became professionalized as a filmmaker by making Memories of a Penitent Heart. In your work, you’re engaging with people who are not filmmakers, who are not professionalized. Could you talk a little more about the role of the amateur in all of this? What does it mean for everyday people to engage in the archives that are before them?

TAH

For me, it became really important to allow for folks, everyday people, to engage their archives more deeply. A lot of my work with communities combines activism, art and performance. I come from an activist family, and early in my career I produced groundbreaking television shows around HIV and AIDS. In the 1990s I taught performance at the University of California San Diego. A lot of my film work provides a platform for people to engage with their archive in unusual and empowering ways. This is reflected in Digital Diaspora Family Reunion. A transmedia project created in parallel with Through a Lens Darkly, Digital Diaspora reframes the narratives around their family albums.

Although Digital Diaspora Family Reunion was initially developed as an online project, I got commissioned to do a live version of it. Through performance, Digital Diaspora becomes a people’s history. I think a lot about Eduardo Galeano’s trilogy Memory of Fire (1985 – 1988), in which he does this reading of the origins of the Americas through people who are anonymous and yet are within the archive. He extrapolates these short chapters moving from indigenous folks, to colonizers, to Africans. Digital Diaspora is working from a similar impulse, providing a space for people to collectively wrestle with the meaning of their images by moving them out of private and into public space. And it’s not just any public space. It feels like in some ways a little more sacred: a sacred public space.

This sacred public space enables people to engage in their archive with compassion. It relates to the title of the film Through a Lens Darkly, a riff off of the First Corinthians’ Bible verse on how we see God, ‘through a glass darkly.’ People can actually begin to see something that ruptures narratives of difference of all kinds: racial, gender, sexual orientation, or even geographical difference. The archive, specifically the amateur archive, is definitely a kind of activist archive. It allows people to find a voice, to value the energy of their archival work.

CA

I think that in many ways my grandmother would be horrified by the way that I have chosen to reinterpret her family history in Memories of a Penitent Heart. On one hand, I feel very indebted to her. She had a huge influence on me morally and spiritually. And yet at the same time, I disagree with just about everything she believed.

Take, for example the role of religion. I think my grandmother felt very much like her responsibility was to be a living, breathing representative of the Vatican. And so in that sense she felt very much like her role in being the keeper of the family history was to reinforce a very particular dogmatic understanding of what it meant to lead a moral life. So if you look at, for example, the scrapbooks that she made, she didn’t just keep family photographs: she captioned them, she edited them, she organized them thematically. She would cut out little phrases from magazines, little catch phrases like ‘I’m here with God” or “A Spiritual Day!” and she would attach them to the photographs. To me, what that constituted was a way of framing this otherwise brute evidence; she was interpreting those images and turning them into her own version of history.

In terms of activism, I decided that it was my responsibility to try and dismantle my grandmother’s frame on behalf of my uncle. There’s a way that Miguel’s sexuality could become a cheap rumor: ‘Oh well, we all knew that he was gay.’ That kind of offhanded dismissal becomes a really terrible way to reduce somebody. For me, an important goal of the film was to capture little details and banalities of Miguel’s life: the contours of his sense of humor, his hobbies and interests, the impact he had on others. In other words, I think part of excavating queer history is not reducing people to their queerness; it is giving them space to exist in all of their nuance. It requires consideration, time, and effort.

It also involves responsibility. The film began with the discovery of this shoebox and a form of active custodianship; my mother literally handed this box to me and said, ‘Keep it.’ Over time, that moment was reproduced over and over again. Sometimes it was me asking people for their stuff, saying to them, ‘Can I keep this? I promise I’ll take care of it.’ Sometimes people would just hand things over to me. By the end of making the film, I had an entire room full of Miguel’s personal effects. I felt so burdened by this weight of responsibility; I felt I had to become a proper archivist and tend to these things in a more careful and systematic way. At a certain point, I began to joke that I just wanted to end the film by piling the archive onto a raft and setting it on fire in the middle of a lake. I wanted an archival funeral pyre.

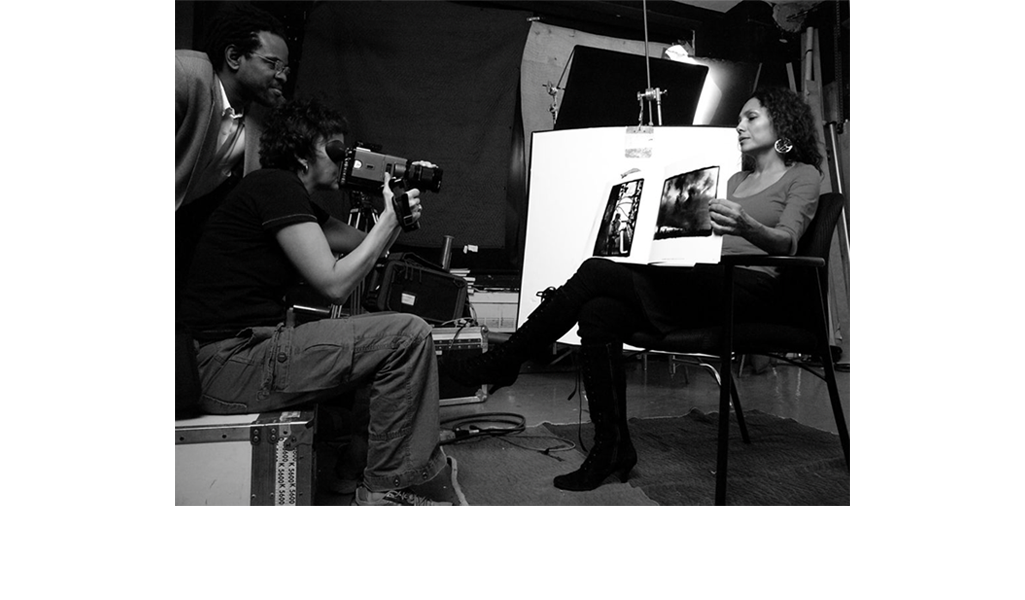

Excerpt from MEMORIES OF A PENITENT HEART (2016).

TAH

I think that we are living in the age of the archive; what you’re experiencing, everyone is experiencing in some way or another. I’ve seen people in Digital Diaspora who have begun books, made films, or started other kinds of genealogical journeys in response to the archive. In about 2012 we went to Brooklyn College to do a big Digital Diaspora Roadshow. As we gave the first seminar around the importance of the archive, a junior teacher at Brooklyn College came to us in tears. He had just inherited two boxes of photographs from his great-aunt, but didn’t know who the people were in the images. He’s a young father with two young kids, living in a small New York apartment. He was overwhelmed, so he threw them out. He put those photos ‘on the raft’ without engaging them. He did not know the value in them, or where they would take him. In engaging with Digital Diaspora for just a few hours, suddenly he was filled with regret. I think that people need to have a sense that it’s a responsibility. When you choose to take on the archive, or an archive chooses you, it becomes a journey.

With each of my films I say, ‘This is the last film where I’m going to do any kind of archival family work.’ And yet I find new material, either in the archives that I already have, or in discovering new archives. It happens regardless of the project’s subject matter. I don’t know if there is really an end in sight. I am regenerating an archive for my future self in 10 or 20 years, and for whoever might inherit it.

CA

It’s a difficult quandary. On the one hand, I think you’re right. The act of ditching or torching the archive can have terrible consequences— irrevocable consequences. But on the other hand, there’s this risk of reproducing or being entirely too slavish to conventional history. I’m thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche’s essay ‘On the Utility and Liability of History for Life.’ Nietzsche is charting what he feels to be his contemporary Germans’ attitudes towards history. One of the modes of history that he identifies is the antiquarian mode. He rails against his fellow Germans, who he feels are so terribly fetishistic about keeping everything from the past, they eventually become completely submerged. For Nietzsche, the Germans become automatons, slavishly reproducing what they think their ancestors would have wanted. The antiquarian devotes himself to a mummification of everything that came before him; ‘the human being envelopes himself in the smell of mustiness.’ {3} And Nietzsche finds this to be terribly dangerous.

One of the things that I have been interested in for a very long time is how artists and activists can engage with the stuff of history in a way that accommodates a certain amount of loss, even forgetting. For me, the imperative to preserve can, in fact, be very brutal. It can mean elevating the needs of previous generations over and above those of the present, or reproducing the overarching ideological power rather than questioning it. It’s like that relative who might exclaim, ‘You can’t say that because of the church!’ or ‘What would your mother say?’ These sentiments have a way of suppressing social change and maintaining the status quo. If you keep everything, then there is no way to interrogate history. It can become a terrible burden. Instead, I want to ask what are the spaces where we can create, where we allow for a degree of speculation, myth-making, or storytelling? How do we cultivate a version of the truth that is, in fact, animated by loss?

TAH

That’s something I struggle with, particularly with other people’s archives that have been shared in Digital Diaspora or our new TV show, Family Pictures USA. I wonder how to have a irreverence, the irreverence of the artist who treats archival material as pliable, who makes it possible for us to use it in new ways. I have been making art from the archive for over two decades, going back to my first feature documentary Vintage: Families of Value (1995), which uses Super 8 and photographs to explore the theme of LGBT families. So for 25 years, the family archive has been my hidden treasure. Many other documentarians come from families of means. I come from a working class family; I have no trust fund. But what I do have—and what has been passed down—is this archive. It has allowed me to tell my and others’ stories in a way that disrupts mainstream, hegemonic narratives around identity and history. That has been so empowering. For example, if it hadn’t been for Deborah Willis curating the work of these black photographers, if it hadn’t been for my stepdad, Lee’s 30-year visual narrative of exile and the emergence of the anti-apartheid movement, I wouldn’t have been able to tell these stories, or to inspire others to understand the importance of their narratives and their archives.

I’m also doing it with other people’s archives, through both Digital Diaspora and my new show Family Pictures USA. It’s not just about excavating these images, but also allowing people to have a certain irreverence with their archive, to be playful even as they might publicly celebrate their family stories.

Artist Viktor Witkowski shares a unique picture from pre-WWII Poland including his Grandfather and his great Aunt

CA

I think of the word ‘conservative,’ for example. The word ‘conservative’ has a double meaning. On the one hand, to conserve is to keep something as it is, to keep it for the future just because you might need it in exactly that form. On the other, to be conservative is also to be ideologically resistant, to say that we don’t believe that things should change. I think there’s a powerful political orientation to the archive that runs through both of our projects. There is a way in which we are not remaining trapped in history, as it were. On the one hand, you’re encouraging people to understand and honor what precedes them, yet not to remain trapped by one’s ancestry. For example, what does it mean to be a queer person who wants to continue to respect their parents, yet also fight to redefine how they are seen? What does it mean to use that history and fight against it in a way that is productive?

TAH

Take the recent controversy at Georgetown, where a dossier proved that the Jesuit university profited from slavery. Or the scandal at Yale University, and their initial refusal to rename Calhoun College—a name that celebrated a slave master—despite the students’ furor. At the same time, there is a new generation of archivists who are calling these institutions to task, and who are looking to filmmakers like us to help them step outside of an official, static interpretation of the archive, to make it more pliable, to bring in those narratives which have historically been suppressed by the mainstream.

Artists help to unearth these other narratives, the histories that grandmothers like yours might consider dirty laundry. Some people don’t want them to be seen, because it’s painful to relive them. My grandmother didn’t. She said, ‘Why should I communicate that pain to you? For some, it might just be easier to allow for the dominant narrative to be maintained.

CA

Every family has things that are ‘better left unsaid.’ In Spanish, the phrase that comes to mind is: ‘hay cosas que no se hablan’ – there are things you don’t talk about. People who do this work, and want to do it deeply, have to have this particular combination of curiosity and irreverence. As you talk, I’m also thinking of the fact that we’re living in the age of the AIDS archive. We’re a generation out from the crisis, and we’re starting to see a mainstream narrative of AIDS history emerging. AIDS is being historicized at the same time that, particularly for communities of color, AIDS is still very much a crisis in the present. ‘Our AIDS America,’ the exhibition that traveled across the United States, was very contentious because of its lack of inclusion of work by people of color.

TAH

This is the reason behind Visual AIDS‘ recent commission of 8 African American artists to make short films around AIDS and HIV, around communities of color affected by the ongoing epidemic which will be shown at the Whitney on International AIDS Day in 2017. I am one of the artists and I‘m focusing on a series of public affairs programs around HIV and AIDS that I produced 28 years ago as a young producer at WNET/Thirteen. This series of broadcasted programs were pioneering in their exploration of how HIV/AIDS impacted my communities — groups usually marginalized by mainstream culture — queers, people of color, women, artists, activists, youth – and how how they responded to the AIDS crisis. Somehow this perspective keeps getting left out of the larger conversation.

CA

If you’re trying to excavate a buried history of the people, or of a minority community such as queer people, there is always a risk of reproducing the same silences of dominant history. I think that right now we’re at risk of producing a mainstream AIDS history that is— in its exclusion of people of color, of women, and of non-Americans—maybe more straight than it is queer. But if we ask the right questions of institutions, if we constantly look for a counter-archive, we can prevent this process. I believe that’s one of the things that activists and artists can do. We can excavate history and resist it at the same time. And I think that’s a very powerful tool.

TAH

There is so much potential for dialogue within the archive, but it’s so critical that we take a dialectical approach rather than re-inscribing hegemony, or insisting on one correct narrative over another’s. With my films it’s important to me to leave them open for the next generation to take and remix them. I wish to have a dialogue with others, to allow for that space of mystery.

{1} See Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Translated by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), and Pierre Nora ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire.’ Representations 26, Spring 1989, 77-25.

{2} Assmann, ‘Beyond the Archive,’ Waste-Site Stories: The Recycling of Memory, 71. Brian Neville and Johanne Villeneuve, eds. (Albany: SUNY Press, 2002).

{3} Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘On the Utility and Liability of History for Life.’ Unfashionable Observations, Vol. 2. Richard Gray, trans. (Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995).