Animistic Apparatus: A Gathering

May Adadol Ingawanij and Julian Ross (Animistic Apparatus)

The curatorial project Animistic Apparatus emerged from May Adadol Ingawanij’s study of the ritual uses of itinerant film projection around Thailand and neighboring territories since the Cold War period.{1} From that research, May Adadol and her collaborators proposed the idea of an affinity or contemporaneity of sorts between the previous century’s ritual practices of projecting films for spirits, and present-day artists’ moving image practices in and connected with Southeast Asia. These two kinds of practices, it turns out, resonate beyond their mutual southern-regional artistic and ritual contexts. Both circle around a shared theme: that artistic and ritual practices are repertoires of agency for humans who are precarious. Both might be approached as practices that make relations and affirm social bonds connecting those precarious humans with other beings in common, and as repertoires of practices of those who have been disempowered by colonialism and global capitalism across different times. Like animistic film-projection rituals, artists’ moving image might be thought of as a practice of agency of those precarious humans who seek new orientations toward other possible futures.

Looking to contemporary anthropological discussions about animism for inspiration, our project approaches artists’ moving image practices as relational, ecological, and cosmological. We are particularly interested in anthropologists who insist upon shifting the terms of discussion away from the colonial notion of animism as the primitive beliefs of the colonized. Tim Ingold, for example, evokes animism as an experiential and relational practice of living. Kaj Århem and Guido Sprenger draw on ethnographic works on animistic practices of Indigenous peoples across Southeast Asia to think comparatively with similar practices in Amazonia. In doing so, they enter into dialogue with Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s theorization of personhood and perspective across ontological categories of being.{2} One strand of thinking conceptualizes Southeast Asian animism in terms of human-spirit relations, which are grounded in hierarchical conceptions of personhood, and in the notion of personhood as a series of contingent states connected to human and nonhuman beings’ capacity to channel transcendental life forces. Århem proposes this concept of Southeast Asian animism in comparison with South American animism, in which personhood is a matter of bodily immanence and shared perceptual capacity among human and nonhuman animals.{3} These speculative endeavors inspired Animistic Apparatus’s efforts to think curatorially about questions of human-nonhuman relations, and they fed our eagerness to situate the project’s starting point in Southeast Asia yet create paths of interrelation with South America and other Global South and diasporic-south contexts.

Animistic Apparatus’s activities therefore tend to take on a constellation of different forms. We place contemporary artists’ moving image practices in proximity with itinerant film-projection rituals performed as offerings addressed to powerful spirits of local territories. We gather, juxtapose, entwine, and invite encounters between contemporary moving image works and Southeast Asia’s scattered genealogies of animism, defined as improvisatory rituals and apparatuses of human-spirit sociality and communication.

For this World Records issue we invited artists involved with our project—whether through participating in an artistic research trip in Udon Thani, northeast Thailand, in April 2019, or through presentation of works within the context of the project’s itinerant exhibitions over the past three years—to respond with fragments of text, sound, and photographic and moving image to two questions:

How is animism part of your practice?

What is your relationship to nonhumans?

Rather than analyzing the artists’ works, we attempt to bring together their responses with our own reflections here. We hope this will be a catalyst for further conversations.

Artists’ contributions by: Félix Blume, Lucy Davis and the Migrant Ecologies Project, Rei Hayama, Sim Hoi Ling, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Juanita Onzaga, Truong Minh Quý, Taiki Sakpisit, Cristian Tablazon, Zai Tang, Fereshteh Toosi, and John Torres.

****

Encounters

Thanawat Phappayon setting up the projection apparatus for Animistic Apparatus, Baan Chiang village, Udon Thani, Thailand, April 2019. Image by Tanatchai Bandasak.

Thanawat Phappayon setting up the projection apparatus for Animistic Apparatus, Baan Chiang village, Udon Thani, Thailand, April 2019. Image by Tanatchai Bandasak.

In April 2019, May Adadol, Julian, and fellow curator Mary Pansanga worked with Noir Row Art Space, one of Udon Thani’s first contemporary art initiatives, to organize an artistic research trip around this northeastern city in Thailand. We were a large group of around forty people, consisting of moving image, sound, media, and performance artists, as well as musicians, sculptors, curators, film programmers, researchers, and journalists. Our plan was to travel to Udon Thani to meet the projectionist troupe Thanawat Phappayon, run by Kasem Khamnak, a talented itinerant projectionist, electrician, and restorer of old projection and audio equipment.{4} We would engage his troupe for three nights, not to project movies as such but to set up their apparatus at outdoor sites around the large city. The troupe would teach our group how to project moving image and audiovisual works using Thanawat Phappayon’s unique assemblage of large-scale tools, its steampunk combination of digital and analog equipment accumulated, repaired, and calibrated over the years to project outdoor films around this northeastern region for ritual and small-scale, entrepreneurial purposes. We would ask Kasem and his small team to give technical help and advice as we organized ourselves into small groups to develop improvised cinematic performances, drawing inspiration from the troupe’s technical assemblage and responding to whatever contingency arose from our few nights of encountering found sites and rehearsing something akin to the ritual of projecting films for spirits.

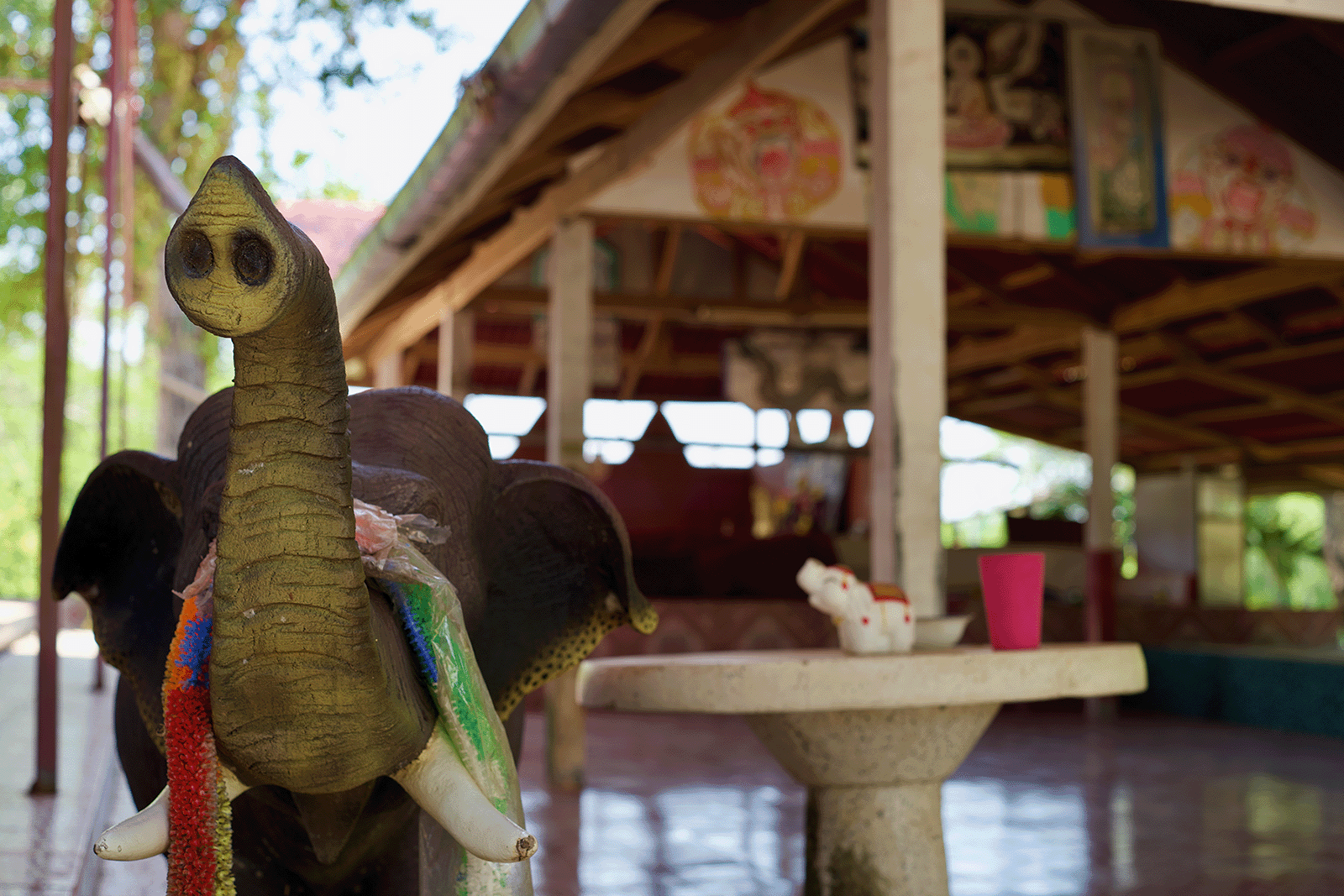

Jao Pu Nong Jok shrine, Udon Thani. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

Jao Pu Nong Jok shrine, Udon Thani. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

One morning during the trip, we visited a local animist shrine whose sovereign spirit goes by the name of Jao Pu Nong Jok (Grandfather Spirit of Nong Jok). We spoke to an elderly local man whose role is that of the jum, the intermediary for this spirit, who warned us that the truth-loving Grandfather Spirit doesn’t care much for offerings of movie projection. The jum told us a story about Grandfather Spirit making a screen catch fire during a projection offering, then announcing through a possessed body that He didn’t approve of the lie being propagated by the movie’s creation of a fictional world, in which the actors are only pretending to be killing each other.

Artist Zai Tang recalls the jum’s story.{5}

I responded to this story by reworking recordings of live improv sessions I did using my field recordings and instruments created by the artist and musician Tarek Atoui. This is my initial effort in feeling my way through the space that [the] jum’s stories opened up for me, via sound.

If we can think of the cinema screen as a door between human and nonhuman worlds, what role might sound play in mediating its opening?

Sound shapes the perceptual and affectual realities we experience, and in relation to the cinematic image it can transform its sensuous horizon in many potential directions. If we see the dance between sound and image as an act of revealing a certain phenomenological fluidity in our experiential reality, then we might consider listening as a means of attuning to these possible worlds that we can inhabit. This audiovisual choreography and process of attunement becomes a gesture of holding open space for alternative modes of perception and affect, and thus contains a potentiality to bridge the gap between beings and between worlds.

Animistic Apparatus participants watching Kasem’s demonstration of lighting up a carbon arc projector from his collection of historical celluloid film projectors. Baan Nong Na Kham temple. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

Animistic Apparatus participants watching Kasem’s demonstration of lighting up a carbon arc projector from his collection of historical celluloid film projectors. Baan Nong Na Kham temple. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

We spent an evening out on the large open ground of a neighborhood Buddhist temple in Udon Thani, projecting images and improvising performances as if we were preparing to make a cinematic offering to spirits. We received permission from local authorities to set up two large screens adjacent to the temple’s crematory. That evening, we became part of an animistic ecology entwining different beings and presences, an ecology shaped by such agencies as spirit hospitality. We soon learned that the question of who can access and perform in this space must be posed to more than just human actors.

Shortly after we arrived at the temple, the moving image artist Cristian Tablazon strayed over to the concrete pyre to gather soot that had accumulated from previous cremations.{6} He then stuck the soot, microscopic remnants of lives once lived, to a found strip of 35mm film, with the idea to enfold this creation from the site into one of his installation works in development.

IF A TREE FALLS IN A FOREST (Cristian Tablazon, 2021).

Later that night, Cristian told us that as he was alone gathering the soot in the fading evening light, the time of phi taak pha aom (ghosts hanging nappies on the line) in the Thai language, he wondered if his gathering of material transfigured from once-breathing bodies was transgressing, or in keeping with, the terms of spirit hospitality. Still, he applied the soot to the filmstrip over several sleepless nights, and the projected result was a short burst of moving imagery made abstract by the smeared particles.

****

Ancestries

After the activities in Udon Thani, the Animistic Apparatus project multiplied out into various activities. While we continued to involve participants of the northeastern trip, we also began reaching out to artists and filmmakers whose practices, despite emerging from regions other than Southeast Asia, resonated with our project. The ensuing screenings and exhibitions—ranging from cinema screens and museum presentations to installations in an eighteenth-century icehouse built into a hill in Berwick-upon-Tweed, northeast England—all provided further opportunities to make and present work as ways of relating to and communicating with a multiplicity of beings, and as ways of inhabiting worlds with a sense of future-making beyond modernist teleology.

Colombian-Belgian filmmaker Juanita Onzaga grew up in what she calls “an environment which acknowledged shamanism as a valid and needed way of understanding life, death, and the beyond.”{7} She considers cinema a way to explore the interconnectivity of life and evoke memory as bodily experience, not only for us but also for the natural world: “How the waters of the soil and the water inside the plasma of our blood remember our ancestors.” In a conversation with writer Michaela Kinghorn, she speaks of seeking in cinema a way to communicate with ancestral spirits:

Some time ago, while having a long talk with a wise Colombian female shaman, I asked her how could I talk with my ancestors; how could I hear them; how could I communicate with them? After staring at me deeply, she said, “As you study your ancestors’ history, as you try to understand your own story and how it unfolds from their paths, when you create with this knowledge, it is them, your ancestors, who write through you.”

This opened a door where I understood that art is a bridge between humans and the otherworldly. Between us and our dead. Between us and our ancestors. Between us and our landscapes, what lives within them.

How do our ancestors talk? How do they still talk to us? How can we talk to them? If from my perspective, time is non-linear, then they can hear us. How can I hear them? Cinema became an active practice to try to answer all these questions; the sole act of cinematic creation became a ritualistic practice in order to dialog with my ancestors and the spirits of the land.{8}

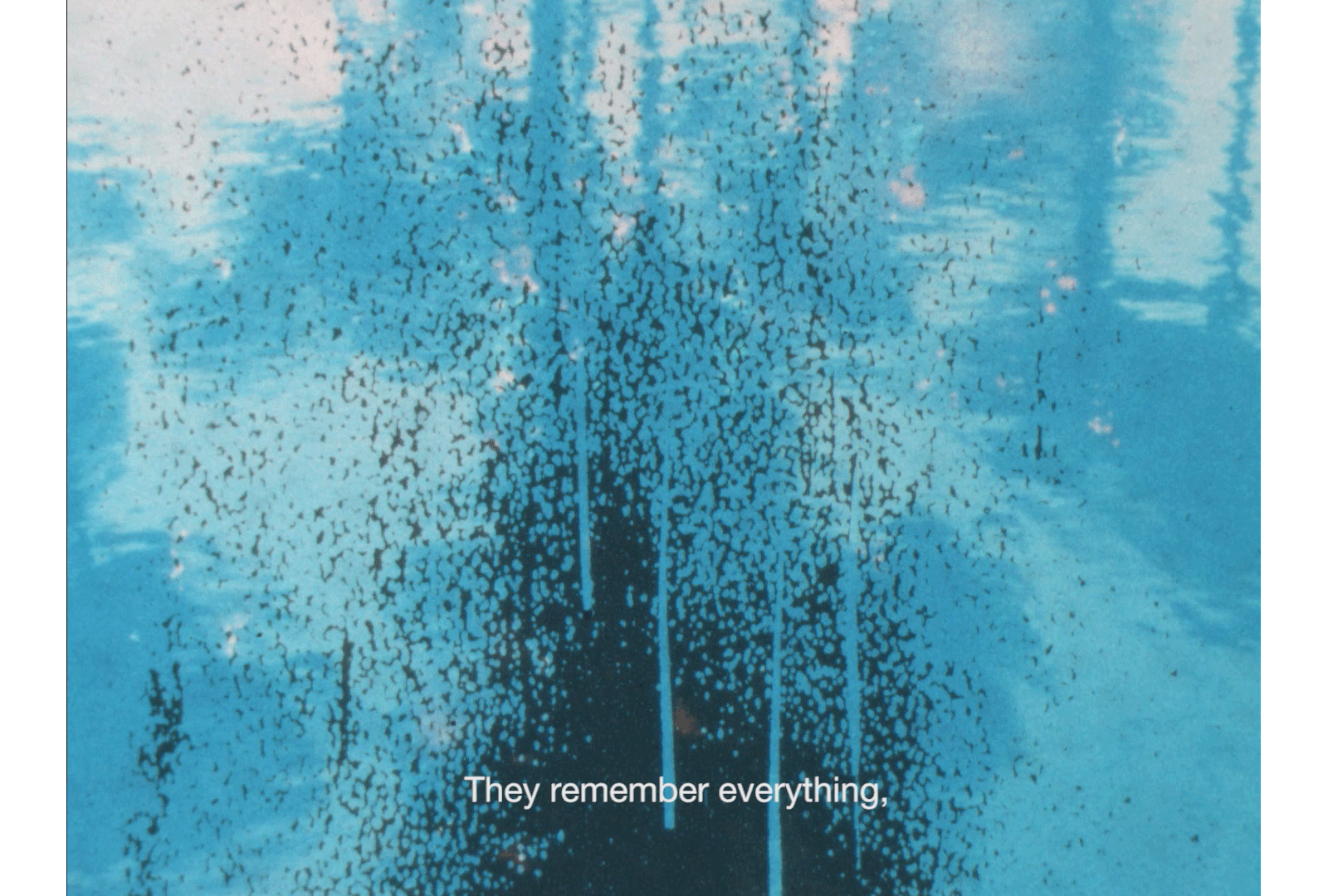

THE BOAT PEOPLE (Tuan Andrew Nguyen, 2020).

Like Juanita, Tuan Andrew Nguyen approaches filmmaking as a mode of communicating and relating with ancestors.{9} Both artists are committed to the role of art in remembering the colonial destruction of their ancestral societies, and in affirming collective capacities to regenerate life in connection with ancestral forces. Tuan’s film The Boat People (2020) is a fable about the arrival of five brown-skinned children on an island at the end of the world, the last five humans on earth. It was shot in Bataan, a town on the coast of the Philippines that had been a landing site for boat people from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, who were displaced by wars and occupation during the Cold War era. On this island, the children in the fable encounter many relics and objects from past times. They make wooden replicas of the found objects, which they then burn. The eldest girl in the group encounters a severed head of a statue-object/spirit-being on the beach. These two beings strike up a multilingual conversation. Speaking with May Adadol for Vdrome, Tuan says,

I am fascinated with our need to preserve some objects and destroy others. I am fascinated with our need to make objects and to make objects of objects. On one hand, I think of replicas as a kind of “reincarnation”. On the other hand, I have to insist that replicas don’t exist. . . .

I think about the idea of a “testimonial object” as offered by Marianne Hirsch and the ability of objects to contain “narrative” and hence to resist political erasure. I think of Vietnamese Supernaturalisms as a subversive system of political resistance as explained by Thien Do in his book with the same title. I think about all the ghost stories from refugee camps I heard as a child.

The little girl’s compassion for the world, which extends to a compassion even for “objects”, leads her to “liberate” the severed statue head (against the statue head’s wishes of a physical liberation, a freedom of movement). There’s an insinuation in the dialogue that this act is possibly a reflection of how she had to care for her mother’s body and her mother’s memory. Vietnam’s recent history is a collision between political and spiritual liberations. I think about the self-immolation of the buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc. I think of traditions in Vietnam like burning votive objects to send to the spirits. Offerings of fruit and flowers on the altar of ancestors. I think of the different ways that burning is used ritualistically in Southeast Asia. A burning fueled by compassion and not destruction.{10}

Florida-based artist-researcher Fereshteh Toosi’s practice explores colonial legacies and ancestral knowledge, drawing inspiration from metaphysical practices of Southwest Asia along with animistic modes of encountering and sensing.{11} Oil Ancestors (2020) is inspired by their experience as a first-generation immigrant of Iranian and Azeri heritage. As Fereshteh states,

Petroleum imperialism has defined the contemporary relationship between my ancestral homeland and the US. The legacy of armed conflict and resource extraction also impacts many Caribbean, South American, and Central American countries that are represented among the immigrant diasporas residing in Miami, where I reside now.

I’m considering ancient fossils, rocks, and minerals as part of our collective heritage. Though the project cannot ignore the industrial function of oil, it asks the audience to consider extracted matter beyond our human use of them as fuel and energy.

How can we practice relating to petroleum as kin?{12}

Fereshteh turns to multiple artistic forms for exploring this question, including performance, audio-based AR experience, an oral history documentation of material and energy transitions, and poetry writing.

Remember when your dead bodies

rained down to the ocean floor?

I was waiting for prokaryotes to spoil me

to be caressed by underwater aerobics

and dissolve in their incantations.And then

breathless.{13}

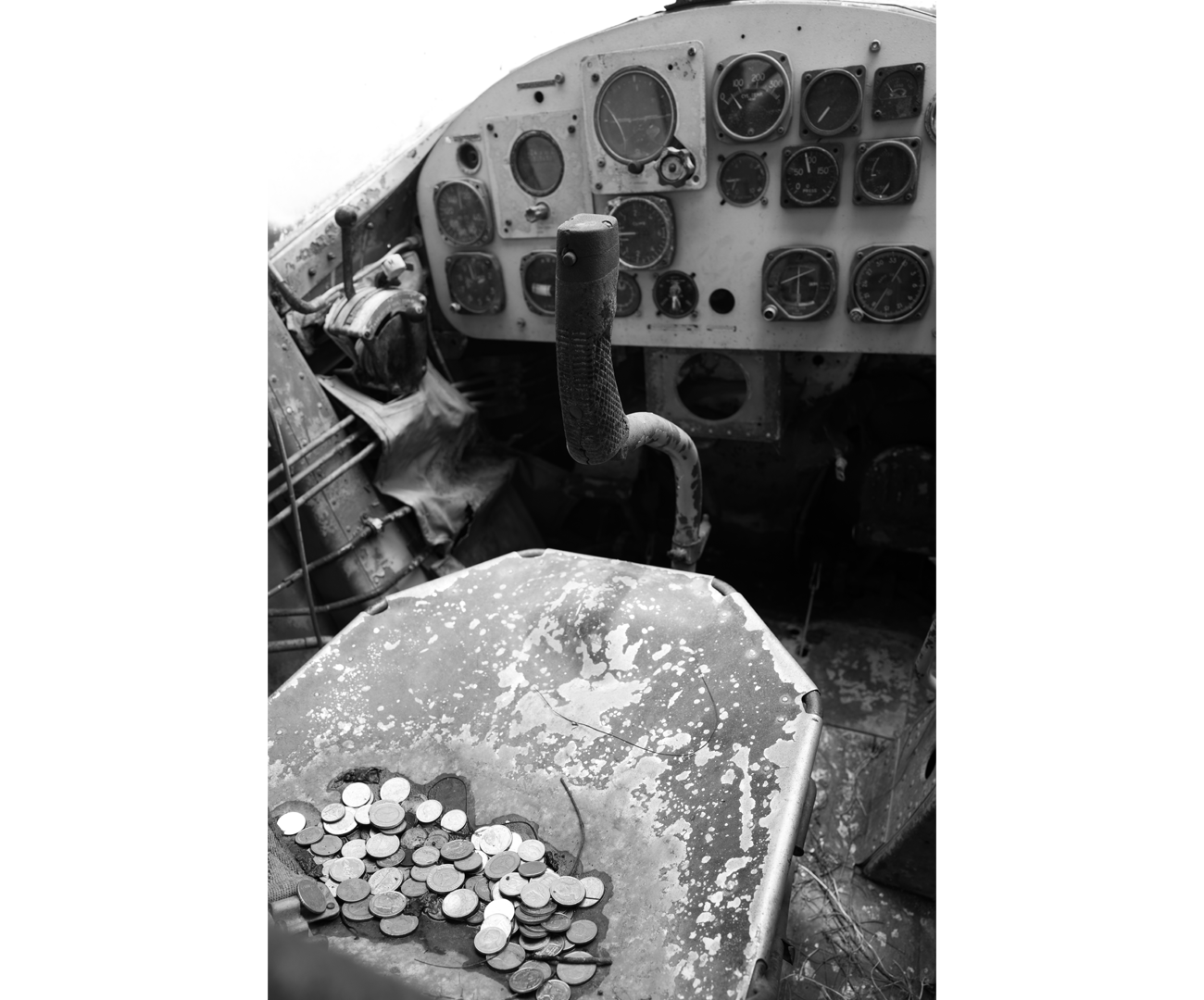

Thai coins found on an artillery and discharged observation aircraft, which operated in the joint area between Phetchabun, Phitsanulok, and Loei provinces in northern Thailand in 1968–83, at Khao Kho War Memorial. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

Thai coins found on an artillery and discharged observation aircraft, which operated in the joint area between Phetchabun, Phitsanulok, and Loei provinces in northern Thailand in 1968–83, at Khao Kho War Memorial. Image by Taiki Sakpisit.

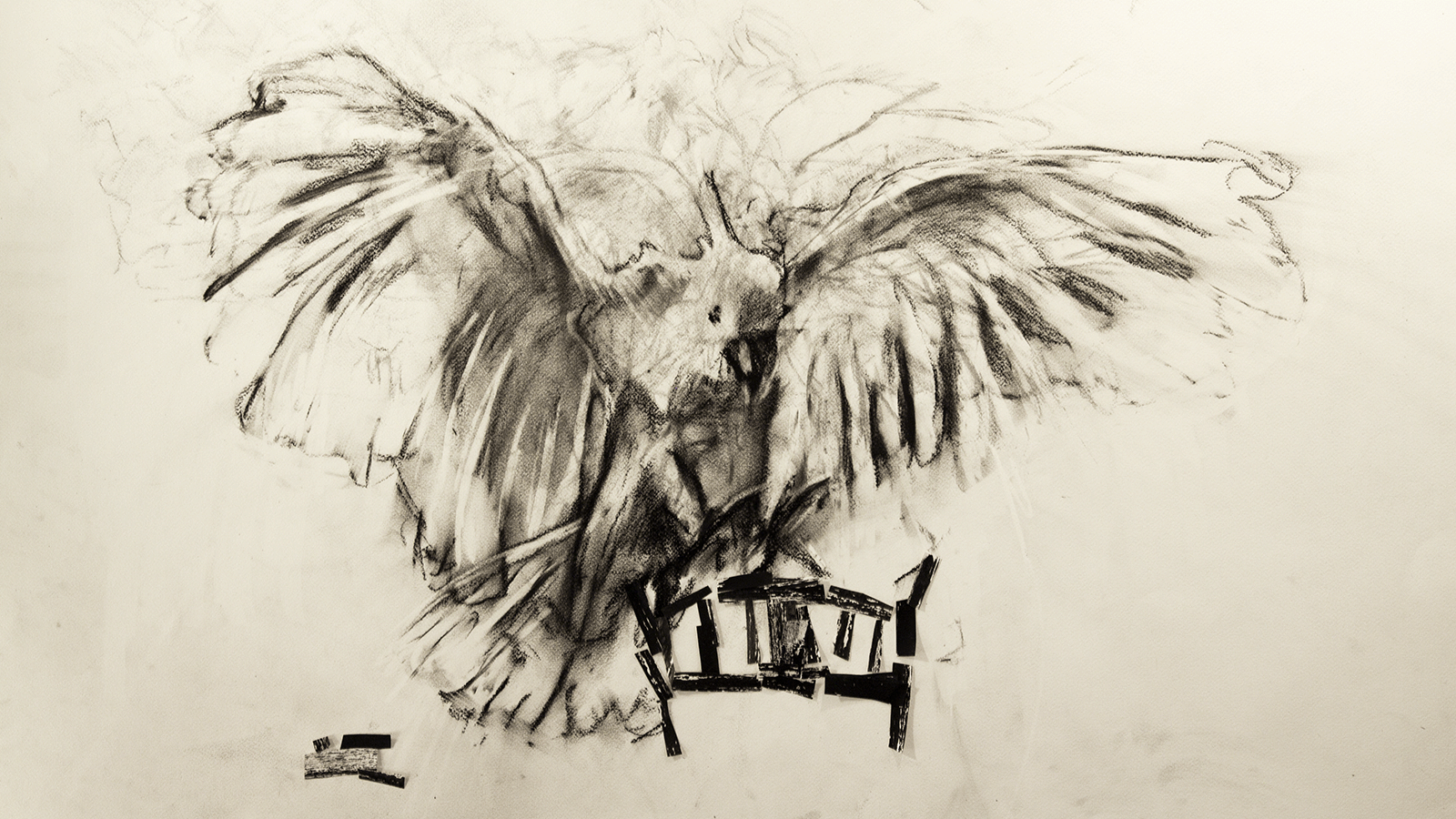

The moving image artist Taiki Sakpisit researches political and historical sites in the Khao Kho highlands in the northern province of Phetchabun in Thailand.{14} The city of Phetchabun was redesigned around the time of the 1932 Siamese Revolution, which aimed to end royal absolutist rule through political and cultural modernization. Today, architectural ruins from this period of political upheaval are scattered across the province. In the highlands, perhaps still present too are the ghosts of the Cold War period of revolutionary struggles, those of peasant members of the Communist Party of Thailand.

Taiki’s video and installation Seeing in the Dark (2021) channels these ghosts by creatively repurposing the travelogue format and making rich use of overwhelming ambient sounds, which heightens the sense of a nonvisible presence. The process of making the work entails photographically recording his trekking in the highlands in search of the traces and ruins of Communist insurgency, doing so with attentiveness to the presence of spirits.

In response to our questions, Taiki sent a photograph taken from a war memorial in Phetchabun, and this fragment of Fernando Pessoa’s poem:

You, the mystic, see meaning in all things.

For you, everything has a veiled significance.

There is a hidden thing in each thing that you see.

What you see, you see always in order to see something else.As for me, because I only have eyes to see,

I see a lack of meaning in all things;

I see this and I love myself, because to be a thing is to mean

nothing.

To be a thing is to be unsusceptible of interpretation.{15}

Taiki’s works might be taken to commune with radical political history through cinematic forms that seem, at once, to address ghosts and to invoke the horizon of the future-possible. Or perhaps they are ritual actions, making offerings to slain radicals as if they were ancestors. Ancestry in this case is not exactly a matter of affirming blood ties or ties of kinship and custodianship of the land.

****

Ecologies

The two questions that we sent to people in the Animistic Apparatus network evoked many responses, most of which touched on the theme of ecology. The artists in the network tend to share a common starting point in associating artistic practice with processes of exploring entanglements in more-than-human worlds, and in their openness to the possibility that artistic modes of inquiry accompanied by technologies extending the human sensorium might facilitate our unlearning and re-sensing of pluriversal worlds.

Sim Hoi Ling in Baan Chiang. Image by Noir Row Art Space.

Sim Hoi Ling in Baan Chiang. Image by Noir Row Art Space.

The most technically complex setup by an artist during the Animistic Apparatus trip in Udon Thani was also the one most in touch, physically, with the earthly elements of our environment. With her knees to the ground, performance artist Sim Hoi Ling spent two nights in intense darkness out in open land in Baan Chiang village, patiently and determinedly connecting an array of wiring to small circuit pads to make a basic sensor monitor for the mysterious performance she had initiated with the artist and poet Red.{16}

Image by Tulapop Saenjaroen.

Image by Tulapop Saenjaroen.

Hoi Ling’s practice proposes technology, and in particular digital technology, not as a threat or an obstacle but as an ecology maker, a connector and enabler of cosmological relations.

There was once an Indonesian shaman who held a ritual in Malaysia summoning the ancestors’ spirits to travel to the place within a specified duration. It took 30 minutes to complete the ritual, summoning the ancestors’ spirits who are 2,365 kilometers away (according to Google Maps). I wonder, does this mean that the spirits were traveling at the equivalent speed of 4,730 kilometers per hour? We can take a step further, converting time distance into digital bytes. The ancestors’ spirits would be tentatively equivalent to 5.4GB of data transferred per hour, assuming it is an average 1.5MB/s bandwidth environment. . . .

Where do spirits go in this urbanized city?{17}

Filmmaker Truong Minh Quý responded to our questions with an extract from his peer Lêna Bùi’s film Flat Sunlight (2016).{18} A woman stands in a pigsty, pronouncing the porousness between life and death. She reminds viewers that death is an everyday, moment-to-moment experience, as cells die and fall off our skin literally all the time.

FLAT SUNLIGHT (Lêna Bùi, 2016).

As flies buzz around and pigs squeal, the woman recites a passage; the simple choice of site sets up an ecology habituating humans and animals. This sharing of worlds between humans and nonhumans was another key theme frequently evoked in the responses of the artists.

Image by Rei Hayama, 2021.

Image by Rei Hayama, 2021.

Similarly, Japanese experimental filmmaker Rei Hayama finds novel ways to locate nonhuman animals in a shared world with humans.{19} She responded to our questions with a photograph of a burial site that she made upon discovering the body of a raccoon dog, a victim of a road accident, accompanied by a text. Rei’s encounter with the body provoked a reflection on how Japanese folktales have reduced the animal to the stereotype of an obese drunkard that persists despite its vulnerability, its struggle to survive the infrastructures forced onto the world by the modern human. She feels resistance to such human imposition, whose parallel she sees in the digital image—in the way that it offers too many functions for control. In her textual response she writes,

Shooting on film was more laborious than video, and each step of the process had an obvious relationship to natural phenomena. Also, there was a special time during the stage of developing the film. You could hear the sound of water in total darkness, smell the chemicals in steam, and feel the gradual emergence of images that you actually could not see. Film’s being is like a rock being slowly chipped away by the ocean waves. Film material is a practice of experiencing the world where we are living. It is an animistic way of connecting with non-human existence too.

Rei’s provocation is to consider analog film to be living. Furthermore, in response to our questions, she asks something fundamental: Why do we need to rethink animism now?

When I think of the folktales and mythical stories that have been passed down through the ages, from a time when humans wrestled with the richness of the earth’s nature, I am reminded of the obvious but often forgotten fact that even those stories told by humans with deep insights into nature are still stories created by humans from a human perspective.

In the age of global warming and mass extinction, what role will humans require of non-humans in the stories we tell? And how can humans interpret these ancient tales today?

Deep down in my heart, I wish I didn’t even have to think or talk about animism!

Every time I say the word “animism”, I feel the mixed emotions of calling out the name of something that will disappear after I call it by its name. It would be a relief if one day this text about animism were to disappear like a message in the sand, lost in the wind or rain. It seems to me that animism requires a lightness of touch, a quick return to being a part of nature. When I think about it, I feel that I am not even qualified to talk about animism, as I was using chemicals for film development, and the laptop which I am typing on right now cannot return to nature easily.{20}

For Félix Blume, digital technology offers, instead, a way into an animal view of the world, albeit one that is mediated by human technology and circumstance.{21} In his collaboration with Sara Lana, a sound piece called Mutt Dogs (2017), Félix attached microphones to Brazilian street dogs in an attempt to get closer to their sonic perspectives.

I’m very interested in the relationship between humans and non-humans, and when this frontier between both categories becomes unclear. In my film Curupira, creature of the woods [2018], this main character which we’re not able to see, but perhaps can listen to, is exactly at the limit between both categories. I’ve been playing with this idea with the sounds, trying to make it unclear if some of the sounds we’re listening to are produced by humans or non-humans.

For Mutt Dogs, we’ve been attaching microphones to street dogs in Brazil, to record their daily life. They’ve been the sound recordists, and we’ve been editing the sound piece with their sounds, trying to give a listening experience from their point of view/listening. Even if I don’t try to forget or to erase my position, I like to try to shift the listening experience to other beings, to listen to them or to try to listen as they are listening (even if this will never really be possible).

I like this relation between the inhabitants (human or not) of a place and their surroundings, and how we could feel a kind of dialogue or conversation between them. I like to consider them as a whole, where “nature” would be everything, and we’re not in front of it, but part of it. I like the idea that trees, rains, have their own voice and ways of claiming their existence in the sonic world.{22}

The experimental practices of Rei and Félix explore how certain aspects of filmic materiality, sonic forms, or audiovisual technology have the potential to evoke a sense of being part of an open whole, even if it is ultimately impossible for people to perceive worlds from the perspective and bodily existence of nonhuman animals. Along with these key questions concerning the creative necessity, as well as the aporia, of imagining other-than-human perspectives, another important consideration is the question of where artistic inquiry is located.

Among contemporary artists in Southeast Asia sustaining a durational and politically committed mode of inquiry into relations between human and nonhuman beings, Lucy Davis stands as an important instigator.{23} In 2009 she initiated the Migrant Ecologies Project as an umbrella for a series of collaborative, transdisciplinary inquiries into questions of art, ecology, and more-than-human connections. Of the project’s method she says,

The way Migrant Ecologies work often involves a very particular more-than-human encounter: an encounter with a 1930s teak bed; an encounter with wheat straw used to stuff a 130-year-deceased taxidermy crocodile; an encounter with a patch of urban scrub; an encounter with a squawking in the canopy. These specific encounters that then draw us into and through thickets of worlds of material, sensorial experience, and story. Common for all these stories is that they evolve through processes of rhythmic returns, to the same place, the same bed, the same grain of wheat, the same interview, the same bird call.

The short film Jalan Jati (2012) combines fable-making with animation and scientific investigation. The story’s starting point is an encounter with an old teak bed in a secondhand shop in Singapore. Technology for tracing the DNA of wood catalyzes a tale of the journey of a piece of wood through time across Southeast Asia, its enmeshment in colonial extractivism and embodiment of Indigenous knowledge, and its transitioning into a commercial object. With this film the Migrant Ecologies Project asks: How might a cinema of wood feel and sound? As Lucy puts it,

When I started this process I was interested in recasting the micro-gestures of a migratory art movement (the mid-twentieth-century Malayan woodblock movement by the Chinese left) and asking what memories of this movement might mean in contemporary contexts of “cut wood,” meaning macro-scale deforestation in Southeast Asia. What I did not realize at the time was quite how disparate a confederation of conflicting stories would continue to emerge from various sites where fingerprints touch wood-grain across the archipelago.

Shannon Lee Castleman wanted to photograph this particular tree in this haunted plantation at dawn. So we got there at 4 a.m., and while the call to prayer announced the arrival of the dawn I looked around the topography of the old plantation, observing how the light began to cast shadows from the large floppy leaves onto a comparatively clear, dry plantation floor. These regular patterns were interrupted sporadically by dark braids of aerial roots and a deeper, knotted shade where a banyan had taken hold, drawing other migrant flora as animals arrived to eat figs and deposited more seeds. As the sun rose, there was a sudden shifting of shadows and movement of light thrown by leaves and branches shaking about in the canopy. I heard a familiar clatter-squawk . . . perhaps a banyan was fruiting? The birds resembled the yellow-crested cockatoo; critically endangered in its native islands and yet escaped crackles thrive in cities like Hong Kong and Singapore. One noisy individual occasionally used to visit the pong-pong tree outside my bedroom window.

This fruiting banyan had drawn me into one of my first intense encounters with a bird zone. My neck straining from swaying backwards and forwards to get a good view of the birds, I began to realize that the active agents of conservation on Muna were neither the forest police nor the few island NGOs nor DNA timber certification, but rather migrating ecologies of cockatoos, banyans, and spirits.{24}

{IF YOUR BAIT CAN SING THE WILD ONE WILL COME} LIKE SHADOWS THROUGH LEAVES (Lucy Davis, 2021).

Another strand of the Migrant Ecologies Project explores the relationship between humans and birds in a patch of land beside a disused railtrack in Singapore. In her response to our two questions, Lucy elaborates on the questions that she and her collaborators were asking as they proceeded with the activities within Railtrack Songmaps, part of which is the recent film {if your bait can sing the wild one will come} Like Shadows Through Leaves (2021).

As we worked, a method came slowly into focus that we now call “storytelling like shadows through leaves.” We imagined making a series of experiences that brought together image possibilities conjured by shifting shadows of leaves, with experience of that sudden clarity when a bird flies past or perches on a branch or an open window and calls and you only hear a fragment of the call and then they are gone but the memory of that sound resounds inside you and you might even find yourself calling back without realizing you are doing it.

A representational method involved randomly sourcing online images of the 105 bird species in this patch and returning, with OHP transparencies of these images, to the GPS location where birds were last seen or heard. A recurring ritual in these returns involved waiting for sunlight in order that a fleeting shadow be cast on nearby leaf, tree, building or pathway. Another approach involved printing hundreds of frames from online bird videos, cutting out the birds by hand and re-animating these or, alternatively, re-animating the bird’s environment, viewed through bird-shaped holds in the paper frames.

The calls and voices are a compilation of fragments of interviews with former residents and nature activists, field recordings of birds in the area, and a selection of oral, species-specific Malay bird pantuns, collated by writer Alfian Sa’at. These pantuns, or four-line poems, include natural-historic evocations of local ecology and birdlife, and were often recited in an improvisational, call-and-response manner; a performance that echoes the competitive calls of birds.

The generous responses to our questions by the artists in the Animistic Apparatus’s network, and these artists’ ongoing contribution to its activities, enable our project to continue with its curatorial thinking. Animistic Apparatus aspires to be a platform for building a southern framework for conceptualizing contemporary artists’ moving image, one whose thinking about modes, forms, and values of artistic research and practices is attentive to multiple genealogies of communicative, cosmological, ecological, and ritual praxes, and one whose forms of thinking with other beings open out from here.

TREES WEARING OUR CLOTHES WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING (John Torres, 2021).

Title video: {if your bait can sing the wild one will come} Like Shadows Through Leaves (Lucy Davis, 2021).

{1} For further context on ritual uses of itinerant film projections, see May Adadol Ingawanij, “Itinerant Cinematic Practices In and Around Thailand during the Cold War,” Southeast Asia of Now 2, no. 1 (March 2018): 9–41; Ingawanij, “Cinematic animism and contemporary Southeast Asian artists’ moving-image practices,” Screen 62, no. 4 (Winter 2021): 549–58; and Ingawanij, “Stories of animistic cinema,” Antennae 1, no. 54 (Summer 2021): 84–103.

{2} Tim Ingold, “Being Alive to a World Without Objects,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, ed. Graham Harvey (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2014), 213–25; Kaj Århem and Guido Sprenger, eds., Animism in Southeast Asia (London: Routledge, 2016).

{3} Kaj Århem, “Southeast Asian Animism: A Dialogue with Amerindian Perspectivism,” in Århem and Sprenger, 279–301.

{4} For an interview with Kasem Khamnak see “From Fish Sauce to Funerals,” Caboose, December 2012.

{5} Zai Tang is an artist, composer, and sound designer based in Singapore. He believes listening is an invaluable means of attuning to and forming deeper relationships with the worlds we perceive and inhabit. His work has featured in Thailand Biennale (2021), Busan Biennale (2020), Singapore Biennale (2019), Singapore International Film Festival (2019), and Yinchuan Biennale (2018).

Note: All artist bios in this text are modified versions of the ones the artists present on their own websites.

{6} Cristian Tablazon works across video, mixed media, and text. He lives and works in Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines, where he co-runs Nomina Nuda, a small nonprofit curatorial platform and exhibition space. He is of Cuyunon-Tagbanwa and Hoklo parentage.

{7} Juanita Onzaga is a Colombian-born, Brussels-based filmmaker and visual artist. In her films, Juanita combines fiction and nonfiction elements, touching the importance of memory, death, and imagination, creating poetic tales that reflect different ways of perceiving reality within strong political contexts. Her work has been presented at Berlinale, Quinzaine des réalisateurs, and International Film Festival Rotterdam.

{8} The full version of their conversation is available here.

{9} Tuan Andrew Nguyen is an artist based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. His practice explores strategies of political resistance enacted through countermemory and postmemory. Nguyen founded the Propeller Group in 2006, a platform for collectivity that situates itself between an art collective and an advertising company. His work has been presented in Sharjah Biennial (2019), Whitney Biennial (2017), and Asia Pacific Triennial (2006).

{10} Tuan Andrew Nguyen, “The Boat People,” interview by May Adadol Ingawanij, Vdrome, accessed August 19, 2022. For some examples of ethnographic research on supernaturalism and the politics of memory in Vietnam, see Kirsten W. Endres and Andrea Lauser, eds., Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011).

{11} Fereshteh Toosi designs experiences that pose questions and foster animistic connections through encounter, exchange, and sensory inquiry. Their artwork often involves documentary processes, oral history, and archival research. They are an assistant professor at Florida International University. In their practice, Fereshteh frequently consults traditional ecological knowledge and cultivates artistic connections to place through a critical social practice of expanded landscape studies, prioritizing Indigenous philosophy over seemingly similar thought systems such as object-oriented ontology. Their project Oil Ancestors earned the 2020 Knight New Work award.

{12} See “Oil Ancestors: relating to petroleum as kin,” Fereshteh Toosi (website), accessed August 19, 2022.

{13} Fareshteh Toosi, “Remember when your dead bodies . . .,” Oil Ancestors, accessed August 19, 2022.

{14} Taiki Sakpisit is a filmmaker and moving image artist working in Bangkok. His works explore the underlying tensions and conflicts and the sense of anticipation in contemporary Thailand, through precise and sensorially overwhelming audiovisual assemblage using a wide range of sounds and images. His work has been presented in International Film Festival Rotterdam, Images Festival, and Yebisu International Festival for Art.

{15} Fernando Pessoa, “[12 April 1919],” in The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, ed. Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari, trans. Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari (New York: New Directions, 2020), EPUB.

{16} Sim Hoi Ling is an interdisciplinary artist based in Malaysia exploring the human condition in relation to the decayed. Her investigation in the geographical qualities of found materials has led her to explore personal emotion-dislocation by using devices such as drawings and sensor circuits in her practice. She has exhibited at KLEX and Melaka Art and Performance Festival, among other places.

{17} Hoi Ling’s online digital media project Fields can be considered a response to her own question; see here. The full version of Hoi Ling’s response to our questions can be found here.

{18} Truong Minh Quý is a filmmaker born in Buon Ma Thuot, Vietnam. His films have screened in the Locarno Film Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, New York Film Festival, and Busan International Film Festival. Lêna Bùi is an artist who works on drawing and video that reflect on ways that intangible aspects of life, such as faith, death, and dreams, influence behavior and perception.

{19} Rei Hayama is a Japanese artist who works mainly with moving images. Hayama’s films revolve around nature and all other living things that have been lost or neglected from an anthropocentric point of view. Her work has been shown at the Barbican (2021), Busan Biennale (2020), and other places.

{20} The full version of Rei’s response can be found here.

{21} Félix Blume is a sound artist and sound engineer. He currently works and lives between Mexico, Brazil, and France. He uses sound as a basic material in sound pieces, videos, actions, and installations. His work is focused on listening; it invites us to a different perception of our surroundings. His work has been presented in Berlinale, International Film Festival Rotterdam, and Thailand Biennale (2018), among other places.

{22} The full version of Félix’s response can be found here.

{23} Lucy Davis is a visual artist, art writer, and founder of the Migrant Ecologies Project. Her transdisciplinary practice encircles plant genetics, tree lore, and bird song, as well as art/science, naturecultures, memory, materiality, narrative environments, and most recently, psycho-ecologies of resilience. She is currently professor of artistic practices in Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art at Aalto University, Finland, where she serves as deputy head of the program. She coedited the special double issue “Uncontainable Natures: Southeast Asian Ecologies and Visual Culture,” Antennae 1–2, no. 54–55 (Summer 2021).

{24} See also Lucy Davis (The Migrant Ecologies Project), “Eco–Art Histories as Practice: Woodcut and Cuttings of Wood in Island Southeast Asia,” in Eco–Art History in East and Southeast Asia, ed. De-nin D. Lee (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019), 165–204.