Everything Can Be Optimized

Benj Gerdes

During the Cambodian crisis in 1969, the school was shut down. The arts faculty, because they trusted their students and worked with them, kept the art department open against the general trend. We were kind of a media center for a lot of movement stuff. We did posters, graphic art, utilitarian stuff for the great movement. One of the problems was that there were all these instantaneous courses and it was a real problem letting people know where they were. Someone suggested the idea of setting up a string of video monitors with a camera and a roller kind of thing to announce these meetings and have them on continuously. We set this up and in the process, borrowed some cheap Sony equipment: a single camera with a 14 modulator strung to 6 RF monitors up the column where the elevator was, which went to all the lounges. I became fascinated with the image. When the meeting was really crowded we put a camera and a mike in there to cablecast. I just became fascinated with the image on the screen, I would sit by the screen and stroke it. — Dan Sandin, Inventor of the Sandin IP Video Synthesizer{1}

In the summer of 1997, I “borrowed” a Super 8mm camera and an issue of Norwood Cheek’s Flicker zine from a girlfriend who had purchased them while living in Athens, Ga.{2} To expose film the camera needed a discontinued mercury light meter battery. I made a few in-store inquiries, then turned to my other growing love: the internet. After scouring overpriced vintage camera websites, I discovered the message board for an online community of camera enthusiasts.{3} A collector on the Isle of Jersey, certain of availability in the UK, offered to send batteries in exchange for a single-use Kodak camera model exclusive to the United States.

This barter, occurring not in a course, workshop or cine club but instead in relative isolation and supported by an otherwise stranger, allowed me to shoot my first roll of film. Prior online and written exchanges—pen pals, zines, and nascent email friends—now culminated in a physical exchange solving a problem both technical (camera needed a battery), economic (scarcity pushed discontinued back stock into premium pricing), and regulatory (discontinuation of mercury batteries in US). Suddenly, new artistic processes outside of the dominant norm opened to me, supported by a communication network offering solutions more economical than that offered to me as an individual consumer.{4}

This account, unremarkable in many ways, points to a condition of emergence for a particular mode of production: camera operations informed by specific online communities, reviews, message boards, and hacks. Across geographic and political boundaries, a mixture of romance, opportunism, generosity, and access signaled the promise of online communities as alternatives to passive commercial consumption of camera technologies.{5} It marked the potential for dialogue and mutually supported experimentation outside of manufacturers’ prescribed uses and outside of capitalist teleologies of technological advancement and marketplace adoption.{6}

Readers of a certain age likely recall the initial promise of digital video and, in the form of MiniDV, the dramatic reduction of production costs when coupled with firewire connections to personal computers: the first editing systems capable of running on personal computers without expensive third-party hardware boxes. Documentarians and video artists quickly adopted certain cameras, owing to the portability and image quality they delivered at a fraction of the cost of larger professional offerings.{7} While online camera support communities emerged with the rise of the internet, they found their raison d’etre with the commercial introduction of these consumer and prosumer digital video cameras. They operated as a collective means of parsing out the proliferation of models amid corporate market diversification strategies, particularly those aimed to retain a professional market while offering versions of the same technology that could develop and meet growing consumer demands.

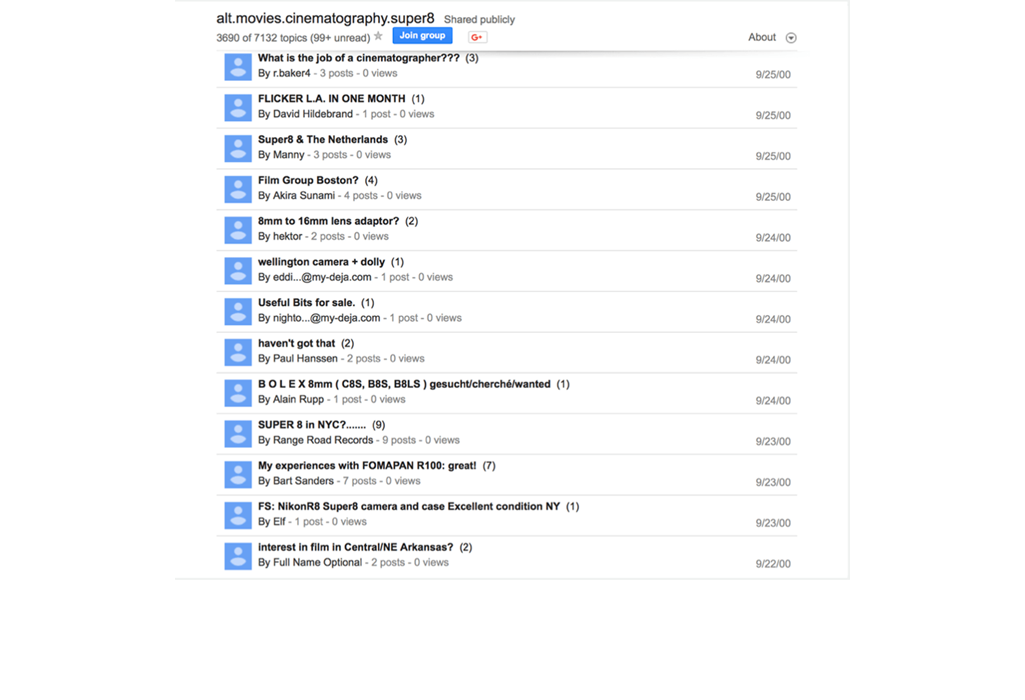

The DVinfo.net homepage as of fall 2004. Note emphasis on “real names” to establish credentials of posters.

The DVinfo.net homepage as of fall 2004. Note emphasis on “real names” to establish credentials of posters.

Online communities now overwhelm the academy’s reach in terms of educating the next generation of practitioners. The scale of these discussions suggests engaged practitioners and teachers must consider their ideological implications. I write from the position of a university media production and studies professor informed by classroom experiences where camera and editing skills present necessary technological competencies, a cluster of potential only activated through a particular project’s specific approach to its topic, audience, and context.{8} As an educator and media maker invested in radical experimental traditions of documentary vis-a-vis pedagogy, advocacy, and activism, my ambivalence focuses on the predominantly non-hierarchical discourse of commenters, tutorials, reviews, and forums privileging and furthering certain modes of production. Specifically, these networks broadly favor the emulation and recuperation of dominant mainstream forms and relationships rather than signaling a difference or departure from them. To revisit many of the revolutionary 20th century aspirations for film and then video, placing the technology affordably in the hands of the many does not yet seem to have fomented the social or political change anticipated on a mass scale. What then is the horizon for this collective work around camera technologies emanating from these impassioned online communities today?

In the late 1990s, new platforms emerged for alternative film and video production discussions. Email lists and usenet groups, the latter a precursor to the message board, with groups categorized via directory by interest (for example, arts groups were a subgroups of the “recreation” directory at rec.arts.X), marked some of the first steps toward a truly open, online space for technical and critical discussion. On the experimental film discussion list-serv Frameworks, an earlier generation of practitioners shared (and continues to share) mostly generous advice and observations with students and other aspirants.{9} This group remained, in fact, predominantly male, territorial, and frequently combative, but the intentional mixture of students, professors, professional film programmers, enthusiasts, and film/videomakers of all ages still stood in contrast to preceding hierarchies of experimental media practice (if not a comprehensive revision). For many years, I subscribed to the net art list Nettime-L but found it too serious to even contemplate posting, while Frameworks felt a little softer and embracing of the hippie/freak trajectory of image experimentation. While transnational in scope, Frameworks emerged from a US/UK-dominated model out of existing cities, regions, and institutions with viable physical experimental film scenes and pre-existing relationships or affinity groups anchoring the terms and tone of discussion.

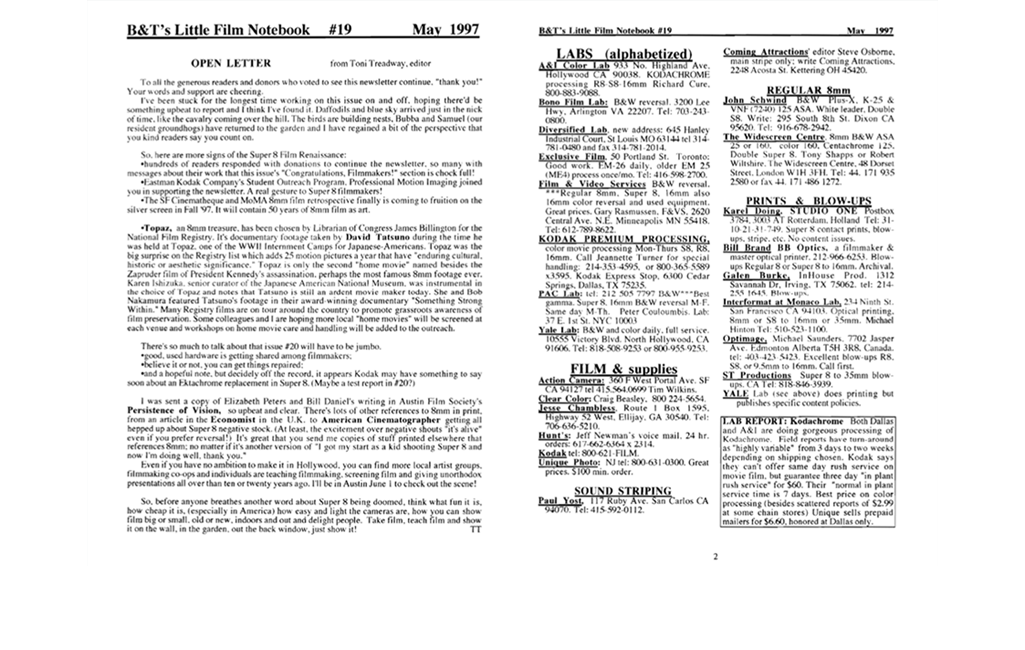

Discussions of 8mm and 16mm-specific zines also carried well into the 2000s. In addition to Flicker, Brodsky and Treadway’s Little Film Notebook offered a more comprehensive source than anything online. For years, the listings of specific labs, repair services, and purveyors of stock and used gear I found here were my true guides; the internet discussion methods were for very specific questions and problems. This, of course, speaks to the decades of community circulation of photocopies and self-published materials offline, a tradition of which Frameworks feels specifically like a continuation. In contrast, the more professionally-oriented rec.arts.cinematography group allowed for very detailed discussions of film stock, lenses, and repairs that had little to do with scenes or education and instead drew loose affiliation based on a shared technical language and investment.{10} While an email listserv archive typically remains searchable, the odd public/private hybrid of the message board offers a specific textual mode—posters and personalities engage and reply directly to each other in a linear and ordered public view. Distinguishing this hybrid mode of address from the broadly similar Twitter or Facebook messages (directed, but public), the structure facilitated conversational responses but supported much lengthier writing. In the latter case, the nature of the public reply in a setting of shared affinity encouraged posts infused with a sensibility of direct reply intended for group edification (offered in a spirit of generosity, this nonetheless can be coded as a kind of cantankerous white male pontification). In theory, this latter mode of communication opens up access to those educationally or geographically on the “outside,” but in a less palpable manner than the subcultural politics of Frameworks as a self-imposed limit, the sharing of technologies as a basis for relating appears to close down other possibilities as well, particularly questions about the goals for these tools as well as critiques of their existing dominant usages and user demographics.

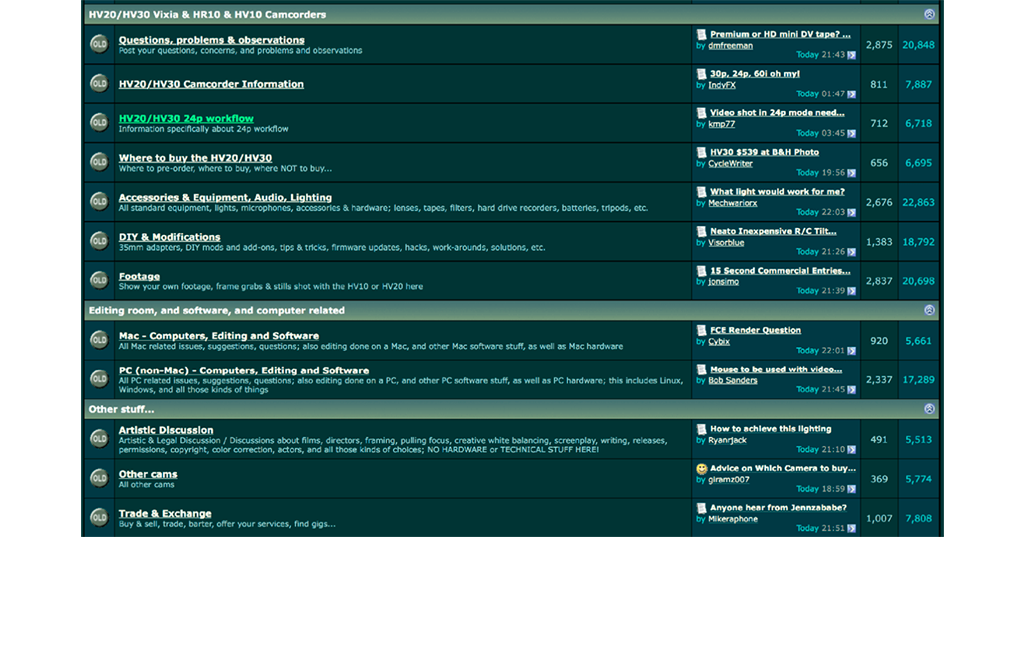

User forum sites such as DVinfo.net or CreativeCow.net (the latter initially standing for “Creative Communities of the World”) also emerged to become vital resources for a growing community of desktop video editors attempting to sort out technical workflows across a spectrum of proprietary, and often incompatible, technologies. Both sites began as support communities for specific technologies in the mid 1990s and grew into broader discussions, with message board functionality implemented by 2001.{11} In both cases, these forums and their widespread user base preceded more camera-specific discussions. Importantly, these discussions covered issues related to overall workflow.

Creative Cow Final Cut Pro Forum, April 2007. Note demographic homogeneity of industry experts at top.

Creative Cow Final Cut Pro Forum, April 2007. Note demographic homogeneity of industry experts at top.

Recording, digitizing tape over firewire to external hard drives, editing, and outputting to tape or DVD were part of this new ecosystem, with each query representing an instance of breakdown in the chain. I witnessed examples of these discussions as a crowd-sourced attempt to formulate new, effective and cost-efficient workflows, albeit one neglecting to evaluate end goals other than to frame the issue.

Many in that moment posited the employment of cheaper things toward expensive-looking projects as punkishly political, a participatory democratization of production.{12} It marks a shift, at least in the worlds I inhabit, from opposition to enthusiastic emulation of mainstream production values. Amateurs, part-timers, and aspiring professional who suddenly felt they could afford to get in on the ground floor interacted with seasoned professionals who delighted in lower-cost, smaller rigs. The emergence of these new affinity groups signaled a crisis in the professional and consumer camera divisions of the big three Japanese electronics conglomerates, who feared the collapse of two distinct markets. To expand into potentially larger consumer electronics markets, video camera manufacturers competed with their own departments as much as they did with external competitors, aiming to strike a balance between entry-level expansion and protection of professional lines. Consider, for example, the omission of professional audio inputs to differentiate lower-priced cameras (with similar imaging capabilities) from their professional counterparts. This condition created an animosity with makers, particularly on the lower end of the pricing scale, which continues today, where the suspicion is often that sensors or cameras are capable but features are disabled or prevented. Users feel limited by and reliant upon the very companies that they rage against. In almost all cases, specific forums and communities came into being to discuss, debate, and optimize these cameras (for example, DVXuser.com is still active today), and more recent examples like reduser.net are quite active. Here we witness a split in the aspirations of forum cultures: some from a DIY ethos, particularly with regards to software, needed professional advice and were off and running, less interested in “professional” results than their own cultivated affordable working methods, whereas the aspiring low budget professionals themselves began to constantly kick at the door, convinced that cheap models could be augmented to rival their costly counterparts, especially when both bore the same brand name on the body.

In the summer of 2007 I purchased a small plastic camera that looked like a toy. The sensor captured 24 frames a second of progressive video (also known as 24p), the first such camera available for less than a thousand dollars.{13} With this model (the HV20), Canon offered its consumers a devil’s bargain. To prevent competition with their own more expensive professional line, these progressive frames had interlaced frames inserted at periodic intervals{14}. One needed to then convert the footage and “extract” the true 24p material. Canon offered no software or guides, leaving it up to the user and presumably hoping the percentage of users willing to navigate this hurdle remained small enough to protect their professional sales. The price, portability, and look of the camera— that it could pass for a tourist shooting and thus fly under the radar— appealed to me. A committed group of users posted to the now defunct HV20.net, parsing out footage transcoding and trick methods for limiting certain auto exposure characteristics to preserve maximum image quality. I had no contact with anyone on this list I would have otherwise encountered in art, experimental, documentary, or political media circles, and I would have had no idea how to work with this camera successfully without this online forum.

Prior to the introduction of HD video DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) cameras, the first mass-produced cameras capable of high resolution video and still photography, message boards for video topics remained a specific sub-community that potentially intersected with still photography only on a personal level. The introduction of HDSLRs signaled a mass convergence between previously differentiated fields of still/moving production as an experienced photo user base that already subscribed to particular lens systems—blue chip camera brands like Canon or Nikon—met advanced video capabilities for the first time. This moment of convergence broadened a discourse of usability, availability, and possibility for new users, incorporating a potentially wider set of interests and applications while setting up a turf war between different modes of production. Tracing shifts in online dialogue and expressions of desire around this widening of moving image practices proves more interesting than tracking the competing camera systems or technical shifts in image production alone. The tenor of these online conversations shifted, with new voices fanning the flames of techno-desire around these ungainly lumps of high tech planned obsolescence, the conversations alluding to the attractions of DSLRs and the approaches to production now most prominent within this shared project.

“…This camera is so easy to use – that you can work incredibly quickly, mostly handheld – without a huge production – and using natural light – ergo you don’t need a huge budget and tons of preparation anymore… forget the lighting trucks and generators that take up entire city blocks…This camera will sell for approx. $2,700 – and perform better than many $100K plus video cameras out there… Photojournalists in particular – will be able to take full advantage of this camera’s strengths – because they are used to walking into any room, and finding the best natural “available light” in the room – or knowing how to add a single light source to make it pop… they are used to working quickly and with small or no budgets… which is something this camera is begging you to do… It has the potential to change our industry.”

In a September 20, 2008 blog post entitled “Something Very Interesting is coming…both to this blog and to our industry,” photographer Vincent Laforet wrote of the pending online release of a narrative short shot with a camera announced just three days prior: the Canon EOS 5D Mark II.{15} The resulting film, Reverie (2008), circulated as a story of numbers: shot with a budget of $5,000 and no plan in under 72 hours, using one battery, the first widely viewed film shot in 1080p on the Canon 5D MKII, and viewed over 2 million times in the first week of its release.{16} Laforet states he had never made a film before. Reminiscent of a classic Mentos commercial, the clichéd imagery and recording of his “cinematic” test shoot at the wrong frame rate and shutter speed attest to the preliminary nature of his moving image practice.{17}

REVERIE, Vincent Laforet (2008)

Unlike a more commercial-minded teaser, Laforet’s initial blog post identifies legitimate technical issues delaying the release of the video; at the time of his writing a video hosting issue remains unresolved. Beyond the fervor of his enthusiasm as quoted above, the comments section of this post is telling: several photographers voice their displeasure at Canon’s inclusion of video on what was until then a still photo line, others offer advice on what nascent video hosting sites support full HD streaming capabilities. Laforet possibly misunderstands the premise of Vimeo, for example, but states, “I’ve already pre-ordered not one, not two but FOUR of these cameras.” Several commenters declare the camera a complete success or failure based on Laforet’s praise and description of the camera’s capabilities. The breathless excitement of Laforet’s blog post foreshadows the tone of many video DSLR conversations in subsequent years. Much like the Sandin Image Processor, a machine about synthesizing new possibilities, no response to the initial post discusses an actual project. Instead, this moment expresses an engagement with the possibilities of the camera’s sensor technology coupled to video, potentialities rather than linear causalities. Finally, this telling exchange:

“MAX ODEN: As a staffer for a daily newspaper that requires I shoot video for nearly every assignment, in addition to stills… this is one of the most encouraging things I’ve read. I will definitely be buying one. Also, Vincent, do you see video production becoming something you do on a regular basis when on assignment?

VINCENT LAFORET: Max – I don’t plan on shooting a single assignment solely with stills ever again… shooting video with is{sic} camera over the weekend ranks up there as one of the most fun things I’ve ever done in my career… I can’t wait to get my hands on this camera again…”{18}

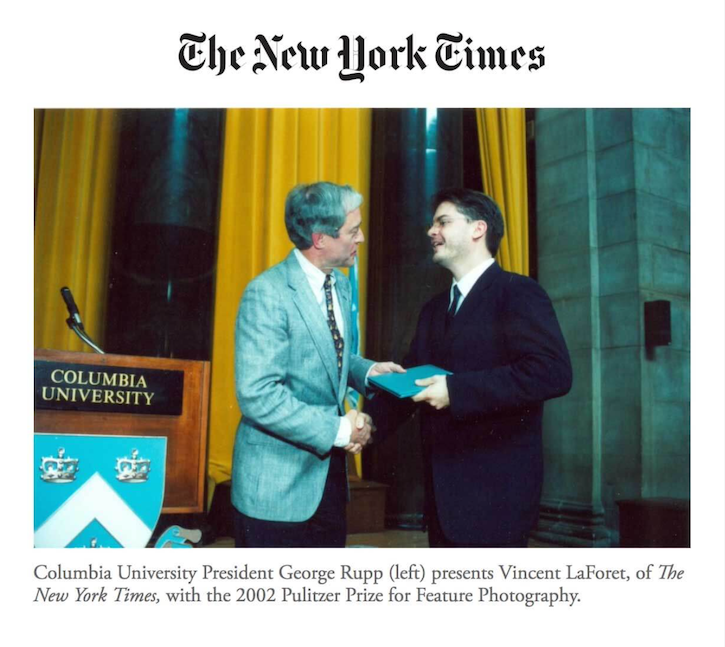

Laforet’s comments exemplify the online hyperbole and technophilia commonly attributed to “fanboys” of various stripes.{19} Perhaps surprising in this context, Laforet’s prior career highlights included the Pulitzer Prize awarded in 2002 to the New York Times photography staff “for its photographs chronicling the pain and the perseverance of people enduring protracted conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan.”{20}

Vincent LaForet receiving a Pulitzer Prize, NEW YORK TIMES, August, 2002.

Vincent LaForet receiving a Pulitzer Prize, NEW YORK TIMES, August, 2002.

I read his review as symptomatic of cultural and professional upheavals leading a photographer distinguished through international coverage of post-9/11 US military actions,{21} for example US-led airstrikes in Afghanistan in October of 2001, to, in 2008, state that a weekend shoot with a new camera constituted “one of the most fun things I’ve ever done in my career…”{22} Perhaps unfairly to Laforet, this line of reasoning traces one such shift away from documenting global conflict and toward becoming a global brand ambassador. While Laforet’s initial review highlights the camera’s specific potential for photojournalists, “Reverie” and subsequent related projects sought instead to utilize Canon’s offering as a low-budget narrative filmmaking tool.

The professional practice of war photography yields straightforward assumptions regarding its resultant psychological effects, but, two months prior to the election of Barack Obama might we draw a broader conclusion regarding a set of practices arriving out of an exhaustion at the end of the Bush era? Would it be unfair to ascribe certain feelings of hope and potential to a given cultural moment, to understand enthusiasm for a camera sensor arriving at least in part conjoined to a broader (US-centric) discourse of “hope and change?” Correspondingly, given the political and cultural moment we now witness (2017), both globally and in terms of the United States, what sort of image and what sort of camera should we be clamoring for today?{23}

Panasonic, Canon, and Nikon’s investment in the HD DSLR boom of 2008- 2009 stoked a significant expansion of video production at the amateur and prosumer level. Notably, cameras from Panasonic and later Sony invited online discussions, reviews, and second-hand resale markets for the resuscitation of older lenses via their newfound adaptability to these cameras.{24} This moment also marked the introduction of the iPhone 3GS with video capabilities in 2009.{25} In both cases, a consumer base of millions bought a phone or still camera and gained the “value-added” feature of a high-quality video camera. While critical accounts of digital imaging often ascribe technological trajectories as a downward deployment from laboratory and/or military applications to professional industry and then consumer level, there exist smaller histories of consumer features migrating up.{26} In the late 1990s, some DV features such as infrared “night vision” found their way onto mid-grade cameras. In a similar sense, Canon’s DSLR division deemed it necessary to incorporate the continuous readout of the digital SLR sensor to an LCD display (“live view”) to attract users of lower-end cameras that already boasted similar functions.{27} Many of course sought cameras like the 5d mkii specifically for its video features, but it’s worth considering the number of people who may found these products a gateway into the “prosumer” video world.{28}

In either case, this created a much broader cottage industry in tutorials, reviews, and release notes for these products, particularly given the technical limitations and issues with much HDSLR video.{29} For those of us immersed in a changing field for some time, witnessing specialist conversations becoming mainstream concerns proved notable. At the same time, the years since then undoubtedly introduced a level of complexity and variation into production processes even for professionals. As these issues now appear tied to consumer product cycles, with shorter timeframe for planned obsolescence (camera updates, lack of ongoing support for older models), all practitioners have likely relied on online sources to sort out production and post production issues related to some aspect of 3D, VR, RAW (uncompressed) footage workflows, the differences between 8/10/12-bit compression and HD/4K/6K/8K, external LCD screens as viewfinders, high bitrate video recording on external devices, double system sound for video, and/or color grading.

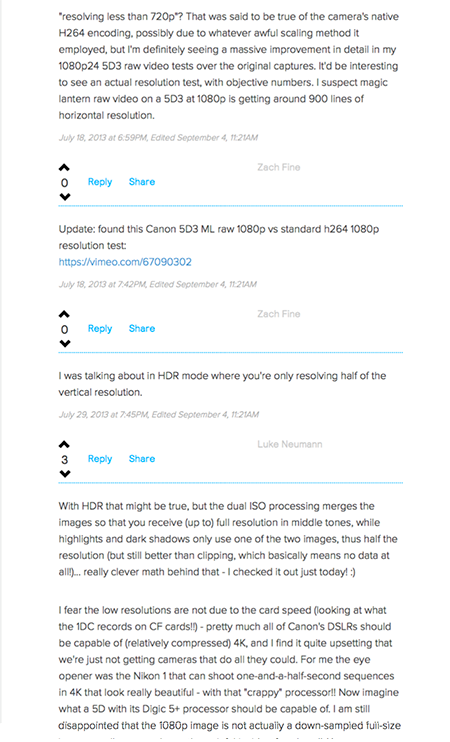

Commenters on NoFilmSchool.com debating the merits of the then-latest Magic Lantern open source

firmware hack on Canon EOS HDSLRs. Similar topics on this and related sites frequently feature

equally detailed technical debates regarding the minutiae of camera performance

Commenters on NoFilmSchool.com debating the merits of the then-latest Magic Lantern open source

firmware hack on Canon EOS HDSLRs. Similar topics on this and related sites frequently feature

equally detailed technical debates regarding the minutiae of camera performance

Paradoxically, as cameras untethered from the material basis of film as a distinct analog technology and instead integrated into digital production, storage, manipulation, and circulation circuits, the camera as a system refracted to a consideration of its technical capacities alone. Many discussions reflect this consideration in a highly reductive manner: the dynamic range of a sensor, the encoding and algorithms for digital video, and the method of reading the pixels of the video frame off the sensor.{30} The optical performance of a particular manufacturer’s lens offering once held more sway than a camera body’s capabilities in a photographic context. The photochemical “sensor” of a 35mm or medium format film camera, i.e., film stock, varied through chemistry but remained constant in the camera’s mechanical intake of it.{31} Similarly, analog and early digital video standards were normalized across a manufacturer era of cameras, with particular models holding currency as flagship or mid-range standard-bearers for several years running. The contemporary reversal serves sales, with optics now subservient to sensors, speed, and encoding; the “read” of the sensor delivered via processing power and algorithmic compression metonymically replaces the camera system as a whole. As a result, the reorganization of the contemporary digital camera market resembles automobile manufacturing and its model year convention more closely than prior logics of still, video, and film camera introduction.{32}

The coincident rise of DSLRs with the late aughts cultural move away from earlier promises of a post-identity internet of reinvention and toward one of self-branded “influencers” and prominent blog personalities positions the primary beneficiaries of this camera revolution within a reconsolidation of white male expertise over a more redistributive or expansive project.{33} Thus, the introduction of the 5D MK II and similar video DSLRs marks the acceleration of a meta-discourse around camera technologies and techniques that has unfolded on an unprecedented scale. I term it a meta-discourse as it focuses in conversation on the conditions and possibilities of production rather than principally a discussion about what has been or is being produced with this equipment. At the same time, these information networks constitute an aspect of the conditions of production, not parallel or ancillary but literally as a support structure. Elaborating on these discursive communities as meta-discourse, perhaps we can even consider an intermediary form of production where the following practices are electronically conjoined: discussions, reviews, empirical tests, instructional videos, product placement, viral advertising, corporate bureaucracy, search engines, Moore’s law, overseas manufacturing and global trade logistics, as well as sexism and (often white) masculinity.{34} Here, cameras as complete systems are understood less as holistic entities and more as assemblages of individually-optimized constitutive elements.

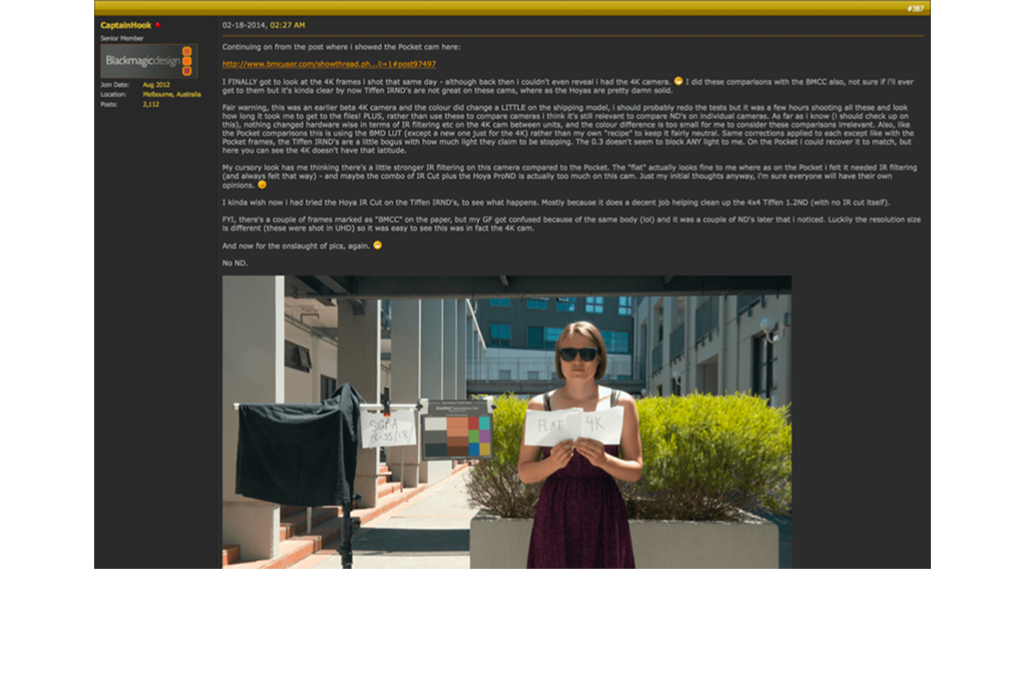

A thread of Blackmagic Cinema Camera users on BMCuser.com evaluating neutral density filters in 2014 includes images of a color chart by DP turned Blackmagic Design employee “Captain Hook.” Subsequent posters

and similar tests imitated this post and used girlfriends, wives, and female employees as on- camera test subjects.

A thread of Blackmagic Cinema Camera users on BMCuser.com evaluating neutral density filters in 2014 includes images of a color chart by DP turned Blackmagic Design employee “Captain Hook.” Subsequent posters

and similar tests imitated this post and used girlfriends, wives, and female employees as on- camera test subjects.

Redsharknews.com story featuring image from the open-source Apertus° Axiom Beta Kit.

Redsharknews.com story featuring image from the open-source Apertus° Axiom Beta Kit.

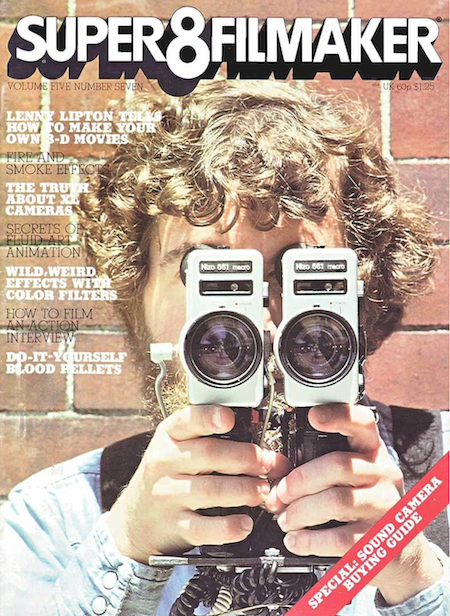

NoFilmSchool.com, founded by Ryan Koo in 2010, features a more diverse staff of emerging writers and filmmakers. The site covers the developments of the camera industry alongside screenwriting and financing tips, and presently appears less focused on reviews and instead in presenting informative and aspirational content for new/younger media makers. Impressively, its content conveys an interest in narrative, documentary, and experimental cinemas. The blend of helpful forms— lists, tutorials, and commentary—resembles the long-defunct Super 8 Filmmaker magazine and its editorial scope, where articles such as Lenny Lipton explaining 3D filmmaking, a tutorial demonstrating title shooting, and an interview with a filmmaker about filming guerrillas in the Philippines could exist side by side.{35}

Cover of Super8filmmaker magazine, November, 1977.

Cover of Super8filmmaker magazine, November, 1977.

Despite the pedagogical approach of NoFilmSchool.com, it operates as a consumer-driven site with sponsored content and almost exclusive attention to commercial offerings.{36} There are several more pedagogically-oriented blogs that devote significant attention to post-production, such as Stu Maschwitz’s prolost.com and Sareesh Sudhakaran’s wolfcrow.net (“workflow” spelled backwards), or the camera tests and commentary of Andrew Reid at EOSHD.com. Aimed at more sophisticated users, their level of detail and generosity differentiates these from industry-minded sites like redsharknews.com and provideocoalition.com that repackage industrial coverage of broadcast video production gear.

To date, the revolutionary rhetoric of new digital image technologies, at least as it is refracted through these examples, exemplifies the move away from decentralized, leaderless sites toward editorially curated and personality-driven review sites with attached discussion forums.{37} Despite the open and democratic premise of many of these communities, and the ultimate attention paid to amateur scientific testing of sensor and video codec performance, the overall ethos remains consumer driven. Witness the oft-repeated trope of commenters hoping, begging, or demanding corporations incorporate specific features in future camera updates and releases. While dispersed globally, these voices typically do not represent the working poor, marginalized, or underrepresented, but instead the educated global middle classes eager to immerse themselves in the latest electronics product cycle. More likely to be electrical engineers than electricians, they rarely seek alternative modes of production.

Optimization represents a cultural logic of rankings and metrics, the identification of empirical winners via general attributes and outside specificities of utilization. Optimization also entails the minimization of risk and, in a broader frame, the programming out of cultures, a turn away from the hoped-for dynamics of participation and contestation many attached to shifts in widespread image production and distribution technologies. The beneficiaries of a plethora of consumer choices and conveniences inhabit contemporary social media and online camera cultures, with the advertised freedom of “choose choice” often belying more brutal structures of social control, surveillance, and exploitation at play in adjacent contexts.{38} Caught in a circuit of aspirations and entanglements, a circuit oscillating between the pure potential of contemporary technology and the rapidity of revision and displacement, exploration and discussion of these choices too easily enacts a feedback loop. In this essay’s title I invoke the term “proto camera” to foreground the anterior logic of these discussions, a shaping of image-making priorities and techniques via (decentralized, extra-institutional) online discourses, but moreover the possibility that practices and productions perpetually flounder in the continual exploration of these choices in isolation. The field of professionals now earning a living through camera review and testing activities breaks from an external emphasis on addressing the lived and/or imagined social world (however flawed or compromised this address may become) toward an internal address confined often to the camera (and then the camera’s sensor) in its technicity. The difference between acclaimed cinematographer Roger Deakins writing in detail for paying members on a blog about techniques and insights gained through feature film production,{39} and the commissioning of short films by noted professional photographers (with large blog/review followings) by companies such as Canon and Panasonic offers a clear example.{40} If the first illustrates a prior model of camera and lighting technique in the service of storytelling, the second points to a world of cameras themselves as anticipatory, always already in a constant state of emergence and hence as potential yet to be fulfilled, one in which the celebrity endorser is often commissioned not on the strength of their creative projects but number of followers. Yet, to reduce these shifts merely to contemporary capitalism seems to overlook the degree to which the scales have tipped in favor of camera fascination. In a moment where many may have engaged and lost their way, staying in the weeds of lens reviews rather than actually engaging the variegated terrain of a wider field speaking to the issues and inequalities of the present. I write this essay partly out of concern of becoming one of them. In the end, what good is the optimal camera system in a world doing badly?

I began with a favorite quote of mine from the video pioneer Dan Sandin. One the one hand, he invented an open source video synthesizer that created new possibilities for the video image. I have used one, they are amazing; tactile, organic, fucked up, unpredictable, and fun.{41} On the other, he started out working to support student protests and ended up fixated on a video screen. He may have put that fixation to better ends than most, but to me this quote always provokes a profoundly ambivalent reaction, one I think of frequently when reading camera reviews. How much is too much information? Whereas once it was very useful to befriend the technician in your film department, or to know someone at a rental house who had conducted side-by-side tests of lenses or cameras, we’ve all become that person, the amateur sensor scientists whose research appears to offer no end in sight. Symptomatically, Dan Sandin made generative machines more than he made videos. The only video I’ve actually seen by him remarkably anticipates generations to come. Here on camera stands the artist-inventor-dude in 1973, wearing a viking helmet while demonstrating what his machine can do.{42}

Dan Sandin with Sandin IP Video Synthesizer.

Title Video: Reverie, Vincent Laforet (2008)

{1} Dan Sandin, reportedly quoting Ars Electronica 1992.

{2} Java Photo Athens, GA. their website remains an eclectic hodgepodge, true to the spirit of the late 1990s web.

{3} It’s likely this was not a motion picture specific usenet group, as in that moment many of the regular 8mm and Super8mm resources were supported by “antique camera” enthusiasts. Alternately, it may have been alt.movies.cinematography.super8 or rec.arts.movies.tech but I’ve been unable to locate my post in either.

{4} Consumerist desires were of course present in this barter, particularly in the collector’s interest in overcoming Kodak’s market differentiation between US and UK disposable camera models. Literally, this consisted of different printing on the cardboard that wrapped the plastic innards.

{5} I also note the attendant educational and class privilege of an in-home desktop computer with free dial-up university internet access through my mother’s job at this time.

{6} Consider this final term in valences of intimacy, elective choice, and force. Technologies are “adopted,” but the act connotes that which we choose to incorporate into pre-existing social structures and that which begins outside those structures. The term “consumer adoption” then reads as a forceful insertion of capital into familial structure and social relations.

{7} Examples include the Sony VX1000 (1995) and VX2000 (2000, appropriately), Canon XL1 (1997) and XL2 (2004), the Sony TRV900 (1998), the Panasonic DVX100 (2002) and its HD successor, the HVX200 (2006), and the HDV Canon HV20 (2007). At some point, each of these cameras touted a technical feature never before available at its retail price, and each found a committed set of users. The DVX100 was in particular a watershed moment as it allowed for shooting cinematic progressive scan video for under $4000 when other options started at $20,000. Tape-based cameras on a spectrum of consumer or hobbyist to “presumer” or entry-level professional comprise this list with the exception of the HVX200 and its proprietary flash memory cards.

{8} However thorougly student-debt generating, ethically compromised, and neoliberal in orientation we find higher education, the classroom setting still supports (unevenly) practices, encounters, and lines of questioning that I consider young people, at least, highly unlikely to encounter in other spaces.

{9} Legendary in some circles for its moments of in-fighting and cattiness, I lost more than one day of my life to the results of flaming and other hostilities. Female posters describe even harsher responses.

{10} There were similar rec. or alt. usenet groups dedicated to film projectors and super8mm as well.

{11} See Chris Hurd’s history of DV Info Net on the about page, as well as Kathryn Lindeboom’s similar history of Creative COW.

{13} The development of progressive standards like 24p, 30p, and 60p and their deployment in consumer equipment represents a watershed moment in the convergence of cinematic modes of video production. For readers unfamiliar with this distinction, progressive video records the equivalent of individual full frames in a manner akin to analog film, whereas older broadcast standards employed interlaced video with odd/even fields deployed as alternating half frames. Interlaced video overall includes the jagged edges that once characterized video as video. It’s hard to explain but if you’re old enough, the jittering of a paused VHS tape demonstrates interlaced video’s lack of actual individual frames. Progressive video generally offers a more fluid image and often an emulation of analog film cameras’ rendering of motion. For an explanation of the difference between progressive and interaced video standards, see Sony user support exchange.

{14} Technically, this allowed 24 frames-per-second to be recorded in a then more common 29.97 frames-per-second container. No practical reason exists for such a confusing setup outside of marketing.

{15} See Vincent Laforet’s September, 2008 blog post.

{16} The edited 2-minute HD video was then originally hosted on the blog of Don MacAskill, founder of photo site SmugMug.com before Canon asked for the file to be taken offline, a sign that Canon was unprepared for the video feature of their new camera to generate this level of excitement (and in particular for it to post a threat to their dedicated professional video cameras, many of which now looked worse by comparison). Canon did no sponsor “Reverie” but loaned a camera. Tellingly, marketing departments brought this approach in-house for subsequent model launches, producing showcase videos in collaboration with prominent blogger and reviewer filmmakers.

{17} Visually evident to viewers familiar with similar distinctions, rate of 30 progressive frames per second instead of the more cinematic emulation of 24 frames per second. He also likely overlooked the most common cinema equivalent shutter speed of 1/48 second.

{18} https://blog.vincentlaforet.com/2008/09/20/something-very-interesting-is-comingboth-to-this-blog-and-to-our-industry/#comment-877

{19} “Fanboys” are often accused of a blindered brand loyalty as this term is tied to a brand or genre (Apple, Nike, Kpop). Correspondingly, as a professional photographer Laforet was already a Canon “Explorer of Light” when he made “Reverie.” See “The effects of self-brand connections on responses to brand failure: A new look at the consumer-based relationship” 2011.

{20} Laforet is picture receiving a Pulitzer on behalf of the New York Times. This page also shows the winning photographs, including many of Laforet’s.

{21} Image captions for Laforet’s winning photos include “Fazal Muhammad, 42, who lost his son in a U.S. air attack on Kandahar in the previous week, is treated in Quetta, Pakistan, for an eye wound in October 2001” and “the mother of Hamid Ullah, 13, grieves over his body in an ambulance after he was killed, with three others, in a demonstration in Kuchlak, Pakistan, against the American-led strikes on Afghanistan.”

{22} The emphasis on camera technology as a qualitative underpinning for the success of a given project illustrates one such shift. I find no discussion of the 2002 Pulitzer that emphasizes cameras or a role beyond normative assumptions for them in this exemplary body of work.

{23} Given that camera and lens sales are roughly shared between US, Asia, and Europe, this is perhaps too US-centric. I base these questions on Laforet’s connection to Canon USA and, given the pre-existing commerical US-based networks for global export on visual cultural, online and otherwise, it is no surprise that the corresponding “DSLR boom” was driven initially by a consumer base in the United States.

{24} Owing to a smaller sensor size or shorter “flange” distance between mount and sensor (a hallmark of mirrorless cameras vs traditional DSLRs), these lens mount standards can accommodate a broader range of proprietary lens mounts: from manual focus 35mm SLR lenses to lenses originally manufactured for Super-16/16mm, broadcast, and cctv purposes.

{25} In many ways, these years are interesting as they signal a massive proliferation but also divergence: the 5D Mk II may be the high water mark of cross-pollination between amateur and pro, hacker and technological conservative, while at the same time the smartphone camera represents a slick but impenetrable interface: it works without any interference, Apple’s hallmark “closed system.”

{26} While the military roots of many imaging applications remain both well known and always in need of further coverage, there exist similar histories of niche industries—such as the casino industry’s deployment of face detection software—that later found wide consumer applications.

{27} Prior to this point, the LCD screens on the back of DSLRs commonly only display a photo after an exposure was taken, relying instead on the viewfinder alone for framing. Point and shoot cameras used different, lower resolution technology and could more readily incorporate a moving LCD viewfinder on account of less information per frame to read out and no mechanical shutter mechanism.

{28} This trajectory now includes popular wearable action/sports cameras like GoPro, delivering a constrained but high-quality image at a similarly unprecedented price point, as well as consumer drones and the widespread recent interest in “entry-level” aerial cinematography.

{29} Moiré, rolling shutter issues, the best “flat” camera profile settings for later color grading, and bitrate complaints were all sources of much discussion. An overabundance of information already exists online if any of these terms are unfamiliar to the reader.

{30} Typically, still images occupy larger pixel dimensions than those of the video frame. Different technical methods—some of which produce visible artifacts—exist for contorting one standard to the other in many mirrorless and DSLR cameras.

{31} While Zeiss and Leica, in particular now sell more lens coatings or design collaborations as high-end brands, look no further for the triumph of processing over optics than the fact that the major inroads in new camera technology have been made by major electronics and computing corporations like Sony and Samsung, on the one hand, or companies with broadcast video hardware backgrounds like Blackmagic Design. Compare this to the “failings” of video integration in cameras by Pentax and Nikon, with their decades of highly developed lens design experience but weaker computing integration.

{32} There are aspects of this phenomenon that are distinct to visual digital media—while pro audio and music recording discussion forums remain every bit as entrenched as their video counterparts, and digital audio development continues at a similar pace, the most popular microphone designs are rooted in 1950s and 60s (for example, condensers like the Neumann u67 and u87) and sought-after preamplifier designs date to the 1970s (API and Neve). While ther exists a cottage industry both in cloning the originals and in digitally emulating them, the conjoining of digital and analog audio technologies still occupies a longer temporal arc than video camera cycles.

{33} The former, more optimistic vantage point may be exemplified by the work of Lisa Nakamura, among others. See Digitizing Race 2007, U of Minnesota Press. A degree of amateur scientificity now saturates the discussion forums and message boards related to video cameras, obscuring the larger racial and gender politics of these spaces which often range from (merely) regressive to (directly) troubling. The class politics remain easily recuperated within the awe of capital’s daily deliveries, those of middle class consumer gain rather than works that look toward restitution or redistribution (think Duty Free shopping disguised as Tarkovsky). One need not look long to come across the warnings signs. Noted photographer and lens reviewer Ken Rockwell’s early aughts pages include a tongue-in-cheek reference to “New York City folk here Bernie Goetz.” Another otherwise serious and overly technical lens review features a sample photo captioned with a joke regarding the “juggs” of a woman in the photo, which I could not relocate for this essay.

{34} In our specific cultural moment, we must add the broader neoliberal tendency to optimize or customize, to seek out “the best” in every detail, often with a segmentation or modular approach tied to metrics. Food (ingredients, recipes), bodies (sex, exercise, sleep patterns), electronics (replacement of individual components, optimization of listening to compressed digital audio with high-end headphones), transit routes (map the most efficient paths), and so on.

{35} All examples of real content.

{36} The aspirational nature means that while it covers a range of emerging and established practices, much of the content affirms the norms of existing industry as goals for their readers, rather than serving as a forum for reimaging these strictures. If lower costs or new tools open participation to new makers and forms, why is it still easier to imagine a site called NoFilmSchool.com than NoFilmIndustry.com?

{37} In some ways, this move toward conglomeration mirrors trends in the camera industry, with long-time industry leaders such as Canon or Nikon today outmaneuvered by even larger corporations with backgrounds in computing, smartphones, etc (Sony, Samsung, Apple) entering camera markets.

{38} The “Choose Choice Anthem” was featured in the 2015 advertising campaign for the Moto X cell phone.

{39} https://www.rogerdeakins.com, see https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/05/09/master-light/.

{40} These include Canon’s subsequent commissioning of short films by Laforet tied to the release of specific camera models: “Nocturne” (2009) for the 1D Mark IV and “Mobius” (2011) for the C300 cinema camera, as well as similarly prominent photo-blogger Philip Bloom’s “Genesis” (2012) using the Panasonic GH3 ahead of that camera’s announcement at the Photokina trade show in 2012. In both cases manufacturers facilitated access to pre-production cameras for videos tied to the announcement or release of the corresponding camera models.

{41} You too can apply to the Signal Culture residency in Owego, NY, if these things interest you.

{42} Sandin, Five-minute romp through the IP, VDB 1973.