Not at the Click of a Button

Text: Ariella Azoulay \\ Images: Aïm Deüelle Lüski

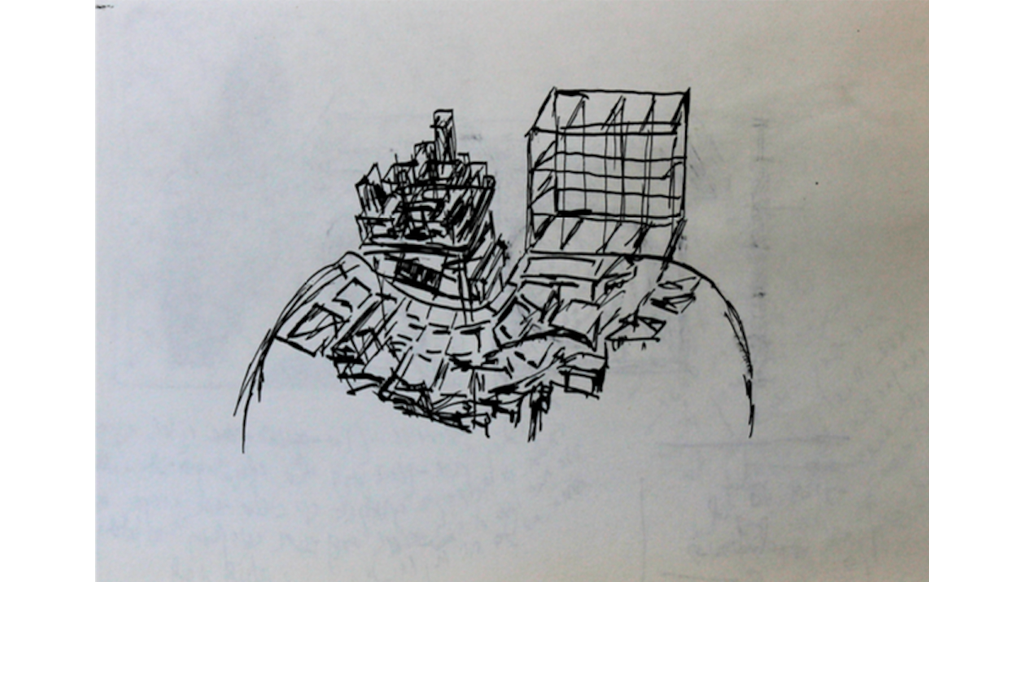

Aïm Deüelle Lüski built his first camera in 1977 during his long stay in Paris. He named it Neighborhood Camera because it consisted of a conglomerate of camera units that comprise a ‘neighborhood’ of sorts. This was a small object roughly embedded into the cover of a small box of Kodak photography paper. Nothing in the shape of this object reveals its essence.{1}

If anything, its amateurish finish reminds one of architects’ morphological sketches prior to the age of three-dimensional imaging. Nothing about it hints at being a camera, let alone the radical criticism it evokes. With multiple sides, fronts and apertures, Deüelle Lüski created an object whose mere existence undermines whatever — throughout the history of photography — has been institutionalized as a camera. 1977 — the year he created the Neighborhood Camera — could have marked the beginning of Deüelle Lüski’s cameras project.

The boxes that Deüelle Lüski builds for his cameras are mostly black, but these are not black boxes. They are not packages of an instrument whose operating mode is known to its producer and operator and can be presented and taught with relative ease in order to obtain foreseeable results. The photographs that these cameras create are not necessarily legible, and cannot be considered identified representations of people, environments, objects or situations. Their certain abstractness bears traces of the environment in which they were created and invites a renewed viewing in our encounter with the world without subjugating this encounter a priori to the triple logic that holds the image as resource, private possession, and object of sovereign rule.

Deüelle Lüski presents one of his cameras in Ariella Azoulay’s THE ANGEL OF HISTORY (2001).

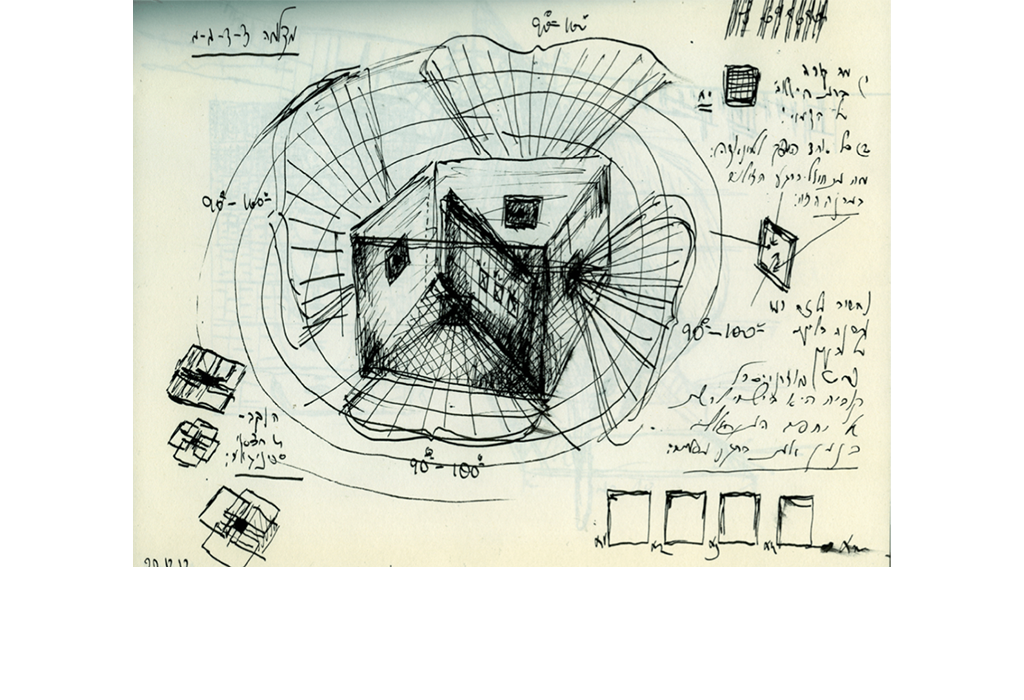

A drawing of North East South West Camera. THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p.8, 22 x 28 cm, 2012.

A drawing of North East South West Camera. THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p.8, 22 x 28 cm, 2012.

North East South West Camera.

Wood and razor blades, 20 x 20 x 20 cm, 1993, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

North East South West Camera.

Wood and razor blades, 20 x 20 x 20 cm, 1993, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

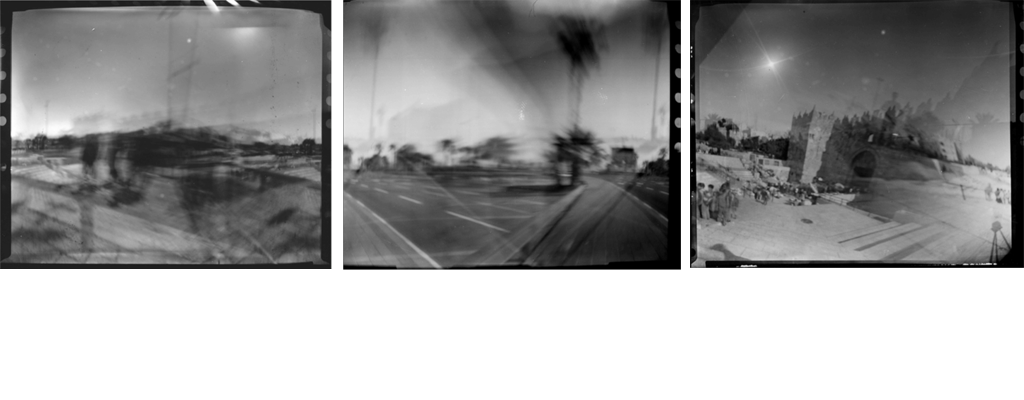

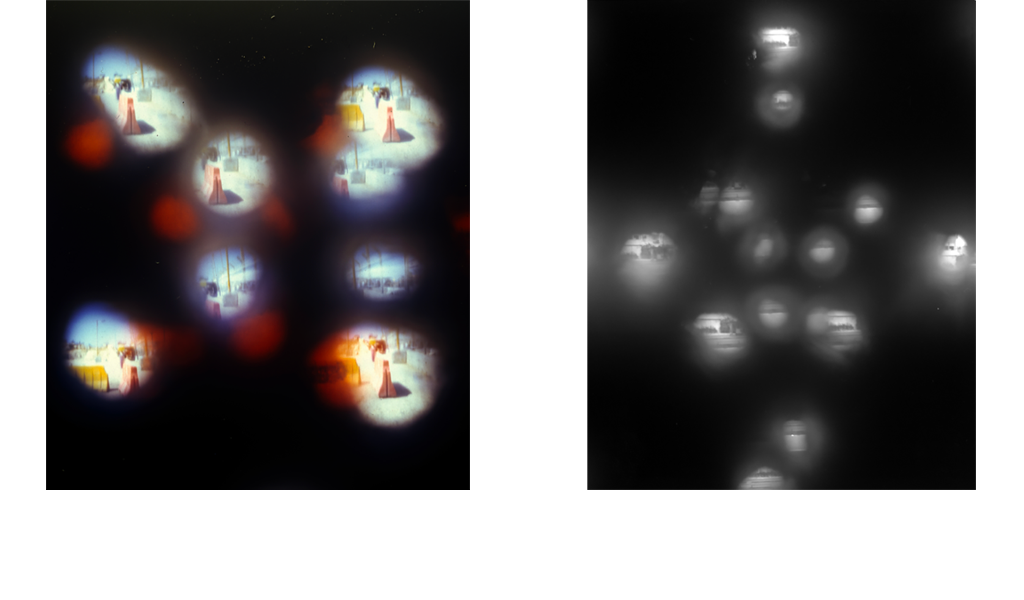

Jerusalem Seamline (1/10), picture no. 1/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992, Jerusalem Seamline (2/10), picture no. 2/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992., Jerusalem Seamline (10/10), picture no. 7/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992.

Jerusalem Seamline (1/10), picture no. 1/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992, Jerusalem Seamline (2/10), picture no. 2/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992., Jerusalem Seamline (10/10), picture no. 7/10, 4 x 5 negative, 1992.

The photographs produced by Deüelle Lüski’s cameras are not ‘photographs of…’ for two reasons: they are not of the photographer, nor of an object to which one could point as though it had been waiting there, already identified, for the photographer to come along. Photography is present as a plural event that cannot be sealed and signed under a heading. Compared to ‘standard’ photographs, these look ‘faulty’. Had they been created in ‘vertical photography’, they would be removed or retouched in order to blur the traces of failure. But there are no failures in Deüelle Lüski’s horizontal photography. ‘Faults’ have always been a part of photography, a part of the event that would not be controlled from a single point of view and therefore something was always missed, superfluous, or disrupting the desired result. The photographer who acts by this logic must reduce the visibility of the failure, and thus preserve the doxa by which a photograph is produced at the click of a button without his interfering in the technology. The history of these efforts is as long as that of photography. Thus, for example, Gustave Le Gray, active in the 1850s, secretly removed without a trace the seams that connected the two different negatives he used in order to create seascapes (one negative was that of the sky and the other, of the sea, and each required a different length of exposure time).

Gustave Le Gray, The Great Wave (1857).

Gustave Le Gray, The Great Wave (1857).

In 1861 Thomas Sutton and James Clerk Maxwell ‘failed colossally’ as they tried to hide the seams between three separate colour plates he used to produce a single-colour image.{2} However, hiding failure was not always handled in the dark. In the years prior to the invention of photography and for a relatively short time afterwards, the process of removing rough seams through which the image took on its typical shape was open to viewing as a kind of wondrous entertainment, like the ‘goofs’ seen on television programs in our days. This is how the stereoscope worked, for example, in which two separate images unite and make up a single three-dimensional image, or the zoetrope that connects several separate images into an image of movement. However these wonder-amusements, too, gradually disappeared for the sake of a switch that instantly provides the results of merging seams.{3}

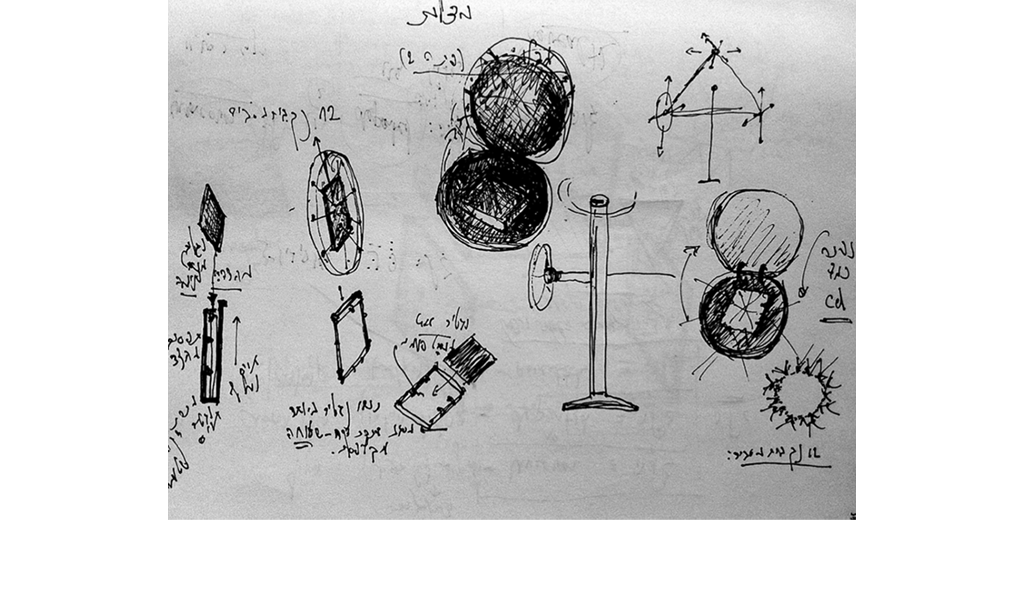

A drawing of Horizontal Camera. THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p. 105, 22 x 28 cm, 2010.

A drawing of Horizontal Camera. THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p. 105, 22 x 28 cm, 2010.

Horizontal Camera II. Mahogany wood, 10 x 10 x 15 cm, 2011, photo: Matan Mittwoch. Horizontal Camera I

(open look), black carton box, 10 x 10 x 15 cm, 1998, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

Horizontal Camera II. Mahogany wood, 10 x 10 x 15 cm, 2011, photo: Matan Mittwoch. Horizontal Camera I

(open look), black carton box, 10 x 10 x 15 cm, 1998, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

The ENSBA school in Paris. 4 x 5 negative, 1998, Self portrait, Paris. 4 x 5 Ektachrome, 1998, The 1st picture with Horizontal Camera. The ENSBA school yard, 4 x 5 negative, 1998.

The ENSBA school in Paris. 4 x 5 negative, 1998, Self portrait, Paris. 4 x 5 Ektachrome, 1998, The 1st picture with Horizontal Camera. The ENSBA school yard, 4 x 5 negative, 1998.

72-Centimeters Clay-Wood Camera, wood and clay, 76 x 10 x 16 cm, 1994, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

72-Centimeters Clay-Wood Camera, wood and clay, 76 x 10 x 16 cm, 1994, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

The Tel Aviv museum square, b/w, full 120 Kodak Tri-X film, 2011, The Tel Aviv Municipality, b/w, full 120 Kodak Tri-X film, 1994.

The Tel Aviv museum square, b/w, full 120 Kodak Tri-X film, 2011, The Tel Aviv Municipality, b/w, full 120 Kodak Tri-X film, 1994.

A drawing of Pita Camera, from: THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p. 45, 22 x 28 cm, 2012.

A drawing of Pita Camera, from: THE SURFACE'S UNHEIMLICH DIARY, p. 45, 22 x 28 cm, 2012.

Pita Camera, Metallic painted casting, perspects, mahogany wood, 15 cm diameter, 2004, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

Pita Camera, Metallic painted casting, perspects, mahogany wood, 15 cm diameter, 2004, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

Back-to-back, Bitounia, # 2, 4 x 5 Ectachrome, 2004, Rothschild Blvd, # 1, Tel Aviv, 4 x 5 b/w negative, 2011.

Back-to-back, Bitounia, # 2, 4 x 5 Ectachrome, 2004, Rothschild Blvd, # 1, Tel Aviv, 4 x 5 b/w negative, 2011.

Cake Camera, Mahogany wood, 40 cm diameter, 2010, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

Cake Camera, Mahogany wood, 40 cm diameter, 2010, photo: Matan Mittwoch.

Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 1/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010., Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 4/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010, Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 5/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010.

Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 1/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010., Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 4/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010, Kefar Shalem’s Ruins # 5/6, 4 x 5 negative, b/w, 2010.

Background: Photos by Aïm Deüelle Lüski

{1} Images and text first published in Aïm Deüelle and Horizontal Photography by Ariella Azoulay, Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014.

{2} This color photograph taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861 following the procedure proposed in 1855 by physicist Clerk Maxwell was considered a failure because it did not manage to blend the seams. Only at the onset of the 20th century with autochrome and color cameras was color procedure packed into a black box that did not require sure great efforts to disguise the difficulty in acquiring it.

{3} On making the wonder present for the viewers through the zootrope, see Rosalind Krauss, The Optical Unconscious, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993. On the abundance of these inventions see, Crary’s book: Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990.