The End of Archaeology as We Know It

Sasha Crawford-Holland with Kisha Supernant

From Canada’s founding until the late 1990s, the government and churches separated an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children from their families and communities and sent them to institutions known as Indian residential schools. These institutions enacted a systematic “policy of cultural genocide” that aimed to forcibly assimilate children into settler society by preventing Indigenous cultures, identities, languages, and spiritual practices from being passed on to the next generation.{1} Residential schools were also sites of physical genocide where thousands of children were killed through abuse and neglect.{2} They were more likely to die at these purported schools than were Canadian soldiers serving in WWII. The full extent of this violence defies comprehension and eludes documentation. Many children were buried in unmarked graves, families were not notified, and millions of records have been destroyed or withheld.

Nonetheless, communities have always remembered their children who didn’t come home. Long dismissed, their stories reached a broader public when thousands of survivors, Elders, community members, and perpetrators shared testimony through a Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2008 to 2015. Among the 94 Calls to Action outlined in the Commission’s final report, they urged the government to support efforts to locate, document, identify, commemorate, and, when desired, repatriate the graves of dead children.{3} Since then, archaeologists have employed the tools of their discipline to assist communities in conducting searches for their missing children at the sites of former residential schools. One person who has emerged as a leading expert in both the technical and social dimensions of this work is Dr. Kisha Supernant.

As a citizen of the Métis Nation of Alberta and an expert in geospatial archaeology, Supernant occupies a unique position. She was trained in a discipline that has actively furthered colonial conquest and dispossession since its inception, and she has devoted her career to transforming archaeology into a discipline that might advance the interests of Indigenous peoples. Supernant has observed that “some archaeologists see this type of work as threatening . . . since it can be interpreted as the end of archaeology as we know it.”{4} In this conversation, we explore the potentials and challenges of such efforts. Supernant’s reflections about the use of sensing technologies to document and reckon with histories of settler-colonial violence hold profound insights for documentary makers and watchers concerned with evidentiary politics, the ethics of collaboration, and media’s role in advancing restorative justice.

****

Sasha Crawford-Holland

How would you characterize archaeology’s historical relationship with Indigenous peoples?

Kisha Supernant

Archaeology has been a very extractive discipline over its history. It tends to come along with colonization and conduct research on the histories of lands that do not belong to the researchers. In many colonial contexts, archaeologists have become the tellers of official history—when people first arrived, how long they have lived here—which is tied up with its use of the scientific method. Archaeology has positioned itself as the source of authoritative knowledge about deep history, especially prior to the arrival of the colonizers, and has often done so with an assumption that Indigenous peoples are either no longer on those lands or don’t have any stake in their own history. This has led to the removal of belongings and sometimes even the bodies of Indigenous ancestors from the land to be placed in non-Indigenous institutions such as museums and universities. These belongings and ancestors have usually been studied without consent from Indigenous peoples.

SCH

It sounds like an unwelcoming discipline for an Indigenous scholar to step into, to say the least. How did you become interested in and involved in the field?

KS

As a teenager, I was captivated by the idea of exploring the world, studying ancient civilizations, Egyptian pyramids—that sort of thing. But when I began studying archaeology during my undergraduate degree, a couple of things happened that set my path in a different direction. One is that I started doing more active work to reconnect with my own Indigenous heritage. My dad grew up in the child welfare system, so he was taken away from his community and his family. I really began my journey of learning about who we were when I entered university.

The other piece was that I had the opportunity to do an archaeological field school collaborating with Indigenous people on-site. We had ceremony, we had community members with us every day, we followed community protocol, and we were taught that there was a responsibility to the living community in the work that we were doing. This was not common at the time, over twenty years ago. It is more common now but still not widespread. That was a formative experience for me. Previously, I’d always thought of archaeology as this intellectual endeavor, something that we did because it was interesting to learn about ancient histories. But this was a different type of archaeology, one that was more than the pursuit of individual interest. It was something that connected that past to the people who are still there in a way that demonstrated how important these places and belongings are for Indigenous peoples. It was an archaeology that was supportive rather than extractive. I learned from them how important this place was to their sense of connection, culture, and identity. I am forever grateful to the Sq’éwlets First Nation for welcoming us onto their territory and so generously sharing their knowledge with us throughout our field school. That was transformative because I realized that there was archaeology happening everywhere in the lands where I had grown up, in the Pacific Northwest. The idea that studying these 3,000-year-old sites could help communities today reclaim what colonization had often taken from them—that connection to the land—was a revelation. It really set me on a different path. I began to ask, What can archaeology bring to the contemporary concerns of Indigenous communities? How can archaeology be a partner?

SCH

One area where such partnerships are being developed to address urgent concerns is in efforts to confront the violence committed against Indigenous children who were held at residential institutions in Canada. Can you tell us about how you became involved in this work and how you view archaeology’s role in it?

KS

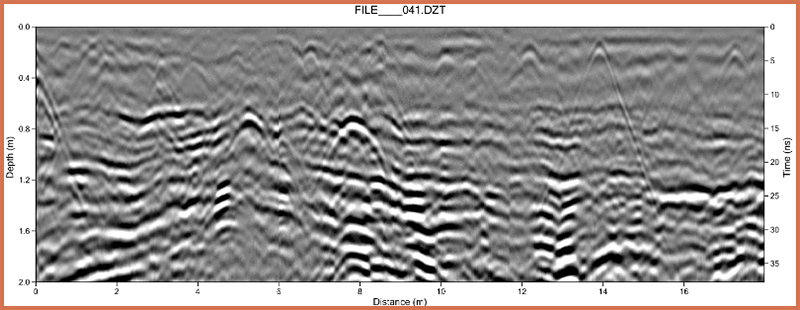

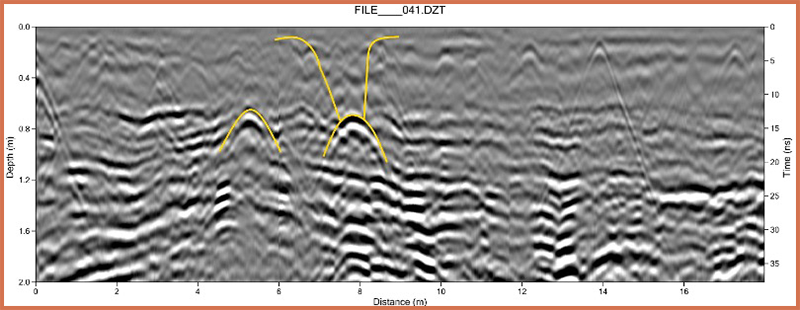

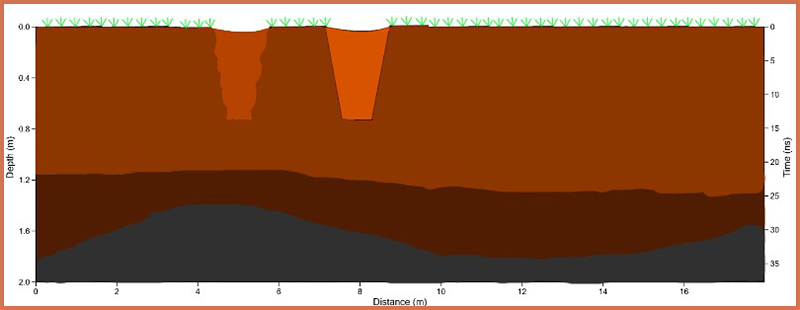

I had never intended to do work in this area. In fact, I studiously avoided working with ancestors because I found it really spiritually and emotionally difficult. But on my journey of learning to be in good relation, people kept asking, “Can you help us find graves?” At residential school sites, and in other contexts of dispossession, communities often become disconnected from places of burial. They know there’s a burial ground but they don’t know exactly where. This came up constantly in my conversations with communities, and I had a set of skills in remote sensing and mapping through my background in geospatial archaeology. In 2018, a colleague was working with the Muskowekwan First Nation to look for unmarked graves at their residential school and asked me to collaborate on a survey. In that case, we primarily used ground-penetrating radar (GPR), which is an established geophysical method for detecting graves in forensics and archaeology. GPR is used to locate potential unmarked burials by emitting electromagnetic waves from an antenna into the ground at varying frequencies. As these waves travel through the soil, they bounce off layers and objects beneath the surface and return to the device, where they are recorded. By measuring the time it takes for the waves to return, researchers can estimate the depth of these objects. Since different materials and soil types reflect the waves in unique ways, GPR provides an image of areas of disturbance or buried objects that can then be interpreted by an expert.

SCH

You began this work in 2018, but it was not until 2021 that the settler public really started paying attention, after Chief Rosanne Casimir of Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced the results of a different GPR survey that identified 215 potential graves near the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This work has entered the spotlight, and you’ve been recognized as a leading expert in the search for missing children and unmarked graves. What kinds of questions can archaeology help to answer?

KS

I’ve been very actively involved in conducting searches, but also in establishing best practices for archaeologists, because many communities turned to us after Tk̓emlúps to help search for their children. It’s important to be clear about what archaeologists can and cannot do in this context because initial media reporting made it seem as though GPR finds bodies—which it does not. We search the ground for indicators of potential graves. We use sensing technologies to detect shapes underneath the surface, but we can’t distinguish, for example, between a pit that’s grave-shaped and an actual grave. A trained expert can distinguish many underground objects, like pipes or rocks, but it remains ambiguous. I’ve been working with colleagues to refine those practices to provide communities with the best information, so that they’re not getting a false impression of what is possible. Using the scientific techniques from geophysics can help locate areas where there are potential graves, especially when combined with other knowledge from archives and from the community. Providing information about where missing children may be located supports communities to address the ongoing trauma of those losses and move forward on their healing journey. It also helps provide evidence of these potential graves to ensure these areas are protected and allow communities to conduct further investigations in their pursuit of justice and accountability.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Figure 3. These images illustrate how GPR search results appear (figure 1), are interpreted (figure 2), and are then modeled (figure 3).

Figure 3. These images illustrate how GPR search results appear (figure 1), are interpreted (figure 2), and are then modeled (figure 3).

SCH

That context seems crucial, because I would imagine there are people who presume archaeological methods to be inherently more authoritative than other forms of knowledge.

KS

Rigor is really important, and it’s not just science that has rigor. Every system of knowledge has internal rigor. Indigenous knowledge is rigorous; it’s not like anything goes. If you’ve talked to an Indigenous Knowledge Holder, they will gently remind you of what the limits of your own knowledge are—what knowledge you have the right to and what you don’t have the right to. And that’s really important! There’s been this emphasis on science as the only true way to know. But we also have our own sciences and our own ways of assessing the world around us.

SCH

One of the remarkable things about 2021 was that the announcement of search results led to mass shock and outcry, even though it has long been a matter of public record that thousands of children died at these institutions. Survivor communities have been saying this for decades. How do media and public opinion affect the work you do?

KS

It’s been an interesting journey since 2021 because, on one hand, you do have a lot more awareness among settlers about the impacts of these institutions we call residential schools. Many were shocked and horrified, and I was like, “Well, clearly you haven’t been paying attention.” The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, while focused on survivor testimony, heard so much about missing children and unmarked burials that they added a whole chapter of their final report on this issue. At the same time, the attention has led to far more support for this work than existed before and has enabled communities to access the financial resources needed to conduct searches. I worry that if it shifts out of the public eye, there won’t be the same kinds of resources that are needed. And this work has barely begun. It’s going to take decades and much greater levels of investment. I worry that without the public pressure, it will just not be prioritized. So public opinion is a double-edged sword. It can really advance things, but it also creates challenges.

SCH

One cost of the media’s spotlight on your work has been that reactionaries engage in bad faith. Settlers who dispute the violence of these institutions weaponize the uncertainty you described to stoke denialism, claiming that reports of harm are unfounded and that these were benevolent institutions. This must add an additional challenge to what is already incredibly difficult work.

KS

I did an extraordinary amount of media—over 150 interviews in just over a year. I chose to take on that burden because I saw the value in having voices like mine in the conversation. Some folks immediately went into a denialist framework to undermine our work, like, “Gotcha! GPR doesn’t find bodies. No bodies have been found.” Well, no, first, that’s not true, but also, there’s an extensive documentary record of thousands of children who died.{5} Thousands. I’ve been subjected to denialist rhetoric since the very beginning and get regular missives from people about how it’s all just a big hoax. These histories create cognitive dissonance for a lot of Christians and a lot of Canadians, in part because Canada has a reputation for being this nice, multicultural, inclusive society. The fact that it’s built on genocide is something that many Canadians just cannot come to terms with. So they deny it and find ways to undermine it, and their voices are growing.

SCH

I wonder if maybe it shouldn’t be your job to deal with that violent backlash—if that engagement with denialists is one place where settlers could play a more active role.

KS

I think so. I have some colleagues, settler scholars, who are doing really good work to counter that, which I really appreciate because I feel like—“Settler collector, you need to call in your people.”{6} It really impacts communities. Tk̓emlúps, which was the flashpoint, needs to have twenty-four-hour security because people are flying drones and threatening to come in with shovels.

SCH

That’s horrific. It imposes this violent imperative to prove what communities already know. Do you ever worry that archaeology can play into their game when it’s perceived as validating unresolved claims?

Outside the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. “At last count, the Kamloops Indian Residential School had close to fifty different nations whose children were taken” (Supernant).

Outside the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. “At last count, the Kamloops Indian Residential School had close to fifty different nations whose children were taken” (Supernant).

KS

We are not going in to prove that children died. That is not our role. There is plenty of evidence already that children died in the thousands at these institutions. We are there to help the community find the potential locations of their children. Sometimes we can provide additional evidence that helps to convince settlers of what survivors in the community already know to be true, but I’m always very careful to say, “I’m not validating the things you already know. We’re using a different set of knowledge practices to hopefully provide some information for you about the specific locations where some of the children might be buried. It doesn’t always work well, it doesn’t always find the answers that you might need or deserve, but we’ll try this other system of knowledge to bring more light to this complex issue.” If the GPR survey comes back empty, I can’t guarantee that there are no burials in that area; rather, I can say the GPR didn’t see anything. If other evidence, such as community knowledge, indicates burials in that area, I’m not disproving it through geophysics; I’m just providing another set of data. It comes back to the point I made earlier, that there are many paths to the truth, not just through the scientific method.

SCH

This distinction between validating and supporting seems key. It reflects how you prioritize communities’ needs in your work. What else, in your view, does ethical collaboration entail?

KS

Ethical work is community-led. This means that it’s not an archaeologist developing an idea for a project and then going to talk to a community. The interest emerges from the community. This is very much true of the work with unmarked graves. None of it happens unless a community approaches me first. But even my other archaeological work is rooted in community interests. I do Métis archaeology—I’m a citizen of the Métis Nation of Alberta—and when I’m working on our history, I always sit down with the community to discuss their priorities. I come back to share our findings and then ask what questions they still have. This can involve meetings with leadership, presentations or workshops at community gatherings, and ongoing conversations with grassroots community members. Then I develop grant applications and project proposals entirely based on those interests. They trust me with the specifics of the technical knowledge, but the driving questions emerge from them. I would really like to see all archaeological work on Indigenous lands being done in that model. We also need to talk about building capacity so that, eventually, they don’t need to come to me; they can do it themselves and have that autonomy. That’s still an uncommon model in archaeological practice. There’s a lot of collaboration, but it’s less common for communities to set the research agenda.

SCH

And even when collaboration is community-led, the colonial system raises additional problems. For example, it’s not necessarily clear what constitutes a community and who should speak on its behalf.

KS

Absolutely. In the Canadian context, the colonial government imposed structures that establish how membership and leadership are defined. Those structures don’t reflect the histories of relation between different Indigenous communities. They draw hard lines around who belongs, who doesn’t, and what the boundaries of the community and the territory are. The principles at the foundation of colonial laws like the Indian Act ignore communities’ own laws and protocols determining membership. There were systems already in place for that but they have been completely disrupted and overwritten by colonial law.

SCH

This becomes especially problematic in the context of residential institutions, where the stakes are so high and many nations are involved.

KS

It’s very complex because each so-called school had children who were stolen from multiple nations. Certainly, some had a much larger population from a particular nation, but there is no “one nation, one school.” At last count, the Kamloops Indian Residential School had close to fifty different nations whose children were taken. So, when you are conducting a ground search, or doing any kind of forensic work, from whom do you seek consent? There are nations taking the lead at the schools on their territories, but so much of the work that we do is ambiguous. Let’s say I do a GPR survey, I come back to the community with findings of some potential graves, and they want to take that next step. We don’t know who is where; we don’t know whose grave we could be digging up. So how do you approach that situation? Ideally, there should be consensus before disturbing the ground, but many nations have different protocols around what happens with the dead. There may be some nations who really want to exhume and other nations who are strongly opposed. Again, these tensions are a product of colonial history. This is not a problem that Indigenous peoples created, but we’re being asked to figure it out, and that is a huge challenge.

SCH

You’ve alluded to the colonial imposition of clear-cut divisions between nations. This seems to be a core assumption underpinning the discipline of archaeology itself, which takes the coherence and continuity of “the nation” for granted.{7} What problems does that create?

KS

This was a challenge that came up during my PhD. I wanted to design a collaborative research project and had, I think, an idealistic view of what was possible. I encountered a colonial legal system being imposed on nations who were related and connected but had been defined as wholly distinct. I was working with the Yale First Nation in British Columbia’s Lower Fraser River Canyon, where they were undergoing a land claims process. Part of the area I was working in overlapped with territory claimed by another community, the Stó:lō Nation. The two nations were in conflict with one another, and I kind of got caught in the middle. The Lower Fraser River Canyon is a really important place for many peoples but it was also being defined and claimed by the Yale First Nation in their treaty negotiations with the government of Canada, which created this hard boundary where there hadn’t really been one before. On top of that, the Stó:lō Nation had benefited from fifty to sixty years of academic research partnerships, so they had this corpus of evidence that they could draw on to assert a certain type of history on those lands, whereas the Yale could not.{8}

That had me reflecting a lot on the power of the knowledge that we generate within institutions—how it can be mobilized by communities against each other and create situations that are not great for anyone. It was really tough but also extremely important. It reminded me that it’s not simple. It’s not like you go and say, “Hey, let’s work together and everyone’s gonna feel great!” No, collaboration is really hard, especially because of settler-colonial processes and barriers—the legacy of reserves, dispossession, and this divide-and-conquer mentality—that affect the archaeological work I do.

SCH

When do we need to be OK with not knowing, with not doing archaeology?

KS

When it has a high likelihood of doing harm. This is perhaps most pronounced in the cultural resource management sector—and the vast majority of archaeology done in North America is done in this context. It’s not academic work; it’s all development-driven and it’s about assessing and mitigating impacts to cultural heritage, meaning evaluating what’s buried in the ground and assessing what can and cannot be impacted by development. Much of it still operates without direct Indigenous input and certainly without the right to refuse—to say, “No, leave that site alone.”{9} There’s no true consent in that process as the decisions about how to proceed are made by regulatory agencies, usually in the provincial or territorial government, based on impact assessments conducted by archaeological consulting companies. Indigenous peoples might be involved in aspects of the assessment in some contexts, but they’re rarely the ones making decisions. Archaeology can be very harmful when the decisions are being made by non-Indigenous people about what is valuable and what is not, about what can and cannot be destroyed by a development project. It impacts our lands and also often our ancestors. It’s important to be able to say that archaeology has harmed and continues to cause harm to Indigenous peoples and other folks who are on the margins of history.

SCH

But you also emphasize that archaeology can be mobilized to repair harm.

KS

I’m not just interested in doing work that doesn’t cause harm. I’m interested in how we can use the tools of a discipline which has been harmful and continues to be harmful to provide redress and restorative justice. How can archaeology promote healing rather than harm? I think there are a number of ways that archaeology, if done in an ethical manner, has a lot of power to support restorative justice, healing, and reconnection. This can include the return of ancestors, belongings, and sacred places to communities. One of the most powerful things for me in my whole career has been to work in the places of my ancestors as someone who was disconnected by colonization. I’ve been able to reconnect with the places of my ancestors through archaeology, to learn about those histories and belongings, but also to do ceremony and connect with community. That has been very healing for me personally and for many of the students that I work with. To feel that sense of connection to living relatives and ancestors is really meaningful. Archaeology shouldn’t just not be harmful; it should be actively undoing and redressing the harm that it has done.

SCH

People often think of archaeology as being objective and dispassionate, but the experiences you’ve shared suggest the opposite. This is especially acute when we’re talking about the trauma of residential schools and what I can only imagine is incredibly painful work. What is the role of emotions in archaeology?

KS

Archaeology has defined itself as an objective, scientific, unbiased approach to understanding history. My archaeological training focused a lot on the statistics, the data, the materiality, the measurements, and it always felt incomplete because, fundamentally, we are studying the vast diversity of the human experience. When we objectify the belongings of human ancestors, they become specimens rather than relatives and contribute to that sense of extraction and disconnection that I mentioned earlier. I’m in archaeology because I’m interested in past people, not past things. The items and the places are a way to explore those people’s lives and stories and experiences. Reducing archaeology down to objective measurements loses so much of the richness of human history and experience. Of course, this is not actually possible, because as humans we are not objective—especially when it comes to history. How do we understand our positionality in the work that we do?

SCH

And that’s where your notion of “heart-centered practice” comes in.

KS

Heart-centered practice is about doing archaeology from the heart, not just the head—recognizing the emotional connections that we have to the work we do. It builds from a long history of scholarship in feminist, Indigenous, antiracist, and decolonial archaeologies that have emerged over the past forty years to create an inclusive and holistic space for archaeological practice that starts from the heart.{10} Many archaeologists describe emotional responses to places or things, but it often stays in the realm of conversation, not academic scholarship, even though emotions are a powerful part of making meaning. If you’ve visited a museum, you’ve experienced how certain objects have affect—they make you feel things. We don’t really have language to talk about that in archaeology. We certainly don’t understand the emotional lives of ancient peoples very well—for example, how people in the past might have made decisions not for status or power but for emotional reasons. One place we’ve seen the most engagement with this is in burial contexts, because there you can see echoes of emotion, whether it’s a mother and a child buried together or two people buried intertwined. Heart-centered practice wants to take emotion from the margins, something you talk about in the hallways, to the center of scholarship, because it’s actually a source of knowledge.

Work around unmarked graves is inherently emotional. It brings up a lot of trauma. Many survivors are sharing their experiences for the first time. It’s emotional for every person involved. It doesn’t matter what their background is. We’re looking for the graves of children. It’s very heavy work and at the same time it’s very meaningful. Leading with the heart helps you connect on a personal level with the people you’re privileged to serve. We attend community gatherings; we participate in ceremony. If we just come in like, “I am an objective scientist,” we will not connect on a human level. It would do a disservice to the relationship.

At the same time, heart-centered practice involves methodological rigor and a commitment to following best scientific practice. Part of the reason that I’ve been so active in helping to develop best practices is that there’s a lot of really bad work happening. There’s this cavalier assumption that if you’ve got the equipment you can find the graves, but it’s actually very scientifically complex. We are always very, very careful about how we apply the science, because the last thing I would want to do is tell a nation I’ve found a child’s grave when that’s not what the science is saying. So having that ethic of care, having that heart-centered approach, actually improves my application of scientific methods.

SCH

I’m intrigued by the notion that technoscientific and heart-centered approaches can be complementary. Many of these issues are also key concerns for documentary filmmakers, since positionality, affect, and relation are always integral to their work, even if their tools seem neutral and mechanical. For instance, I’m curious about potential connections between recording something with a camera and with GPR. What’s the sensory experience like? Is there a feeling of emotional intensity?

KS

There are many sensory aspects to archaeology. It’s a highly physical activity. When we’re doing GPR, we don’t know things for certain in the field, but we do know the difference between where there’s nothing and where there could be something. It’s like a blank, flat screen versus a noisy screen. The visual alone doesn’t tell us that we’re encountering graves, but often the experience of the team does. We tend to have a pretty good instinct of when we’re walking over graves. There’s something in that experience. My work with Muskowekwan was one of the first times I directly experienced this. We surveyed several areas, but there was one where we all just felt this heaviness—the steps were harder to take and there was a pressure, almost. That ended up being the most active of the grids, where we identified the most potential graves. I’ve experienced that in other places too. You feel it in the moment. Everyone gets quieter, everything gets more serious. You can feel the presence of those ancestors.

“We aim to create an archaeology that speaks to the whole person—our intellectual, emotional, spiritual, and

physical selves. . . . The heart berry [is] the name given to the wild strawberry by many cultures, from Indigenous nations to the ancient Romans, Greeks, and other Europeans, because of its shape and color, its literal power as a heart medicine,

and its more figurative power as a source of healing” (Natasha Lyons and Kisha Supernant, ARCHAEOLOGIES OF THE HEART).

“We aim to create an archaeology that speaks to the whole person—our intellectual, emotional, spiritual, and

physical selves. . . . The heart berry [is] the name given to the wild strawberry by many cultures, from Indigenous nations to the ancient Romans, Greeks, and other Europeans, because of its shape and color, its literal power as a heart medicine,

and its more figurative power as a source of healing” (Natasha Lyons and Kisha Supernant, ARCHAEOLOGIES OF THE HEART).

SCH

Do you feel an obligation to them as well?

KS

I feel a strong sense of responsibility to the ancestors, especially with the unmarked graves work. They have pointed me in this direction. They have said, “We need the gifts you have. We need them to help find us, to heal.” It’s one of the things that has allowed me to keep doing what is very heartbreaking work. Because I feel that sense that they’re really grateful to have an Indigenous person who can come in and do this work; grateful to have a relative. I have relatives in most of the places where I do groundwork. I’m potentially finding the graves of my own relatives. Because I take this work as very sacred, centering community and centering ceremony, I feel that responsibility, but I also feel that support that the ancestors are behind me and that they’re helping with every step that I take. Otherwise, I don’t think I could take another step on a grave.

SCH

Thank you for sharing that. I think much of what you’ve described resonates profoundly with the experiences of researchers and media-makers, especially those reflecting critically on their responsibilities when sharing other people’s traumatic histories. What advice do you have for media practitioners working in other contexts to document histories of violence?

KS

I think heart-centered practice is possible in any context. It’s not unique to archaeology. Anyone who has a heart can be heart-centered. We’re whole humans in all this work that we do, and when you are documenting histories of violence, it’s particularly important to come with the heart. It’s also really important to care for yourself. Working in these environments that are full of trauma can be very difficult. For myself, I have my own intergenerational trauma that gets triggered when I’m doing this, so making sure that I have the supports that I need has been really important. It can wear you down. It can be too heavy. For example, I always encourage my team to participate—when invited—in community ceremonies, gatherings, or other ways of coming together and healing, because it uplifts our spirits as well. Recognizing that we are always impacted by the work that we do and making sure we have ways to care for our own hearts as we put them out there is really, really important if we want to sustain this work. It’s better to have you there than someone who thinks they can bracket emotions from the process, because that has the potential to perpetuate harm.

SCH

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

KS

The ultimate motivation of my work is to build better futures. I study the past, but a lot of Indigenous communities have teachings about the relationships between previous generations and the generations to come, and what motivates me is wanting to build a better future for my Métis daughter and for the generations that come after her. It’s not about reliving the trauma of the past; there’s a danger of emphasizing the trauma of this work.{11} That sense of survivance—of building better and brighter futures for Indigenous peoples, but also for the world—is the core of what I do.

Title video: “Ground-penetrating radar results at site of former Beauval Indian Residential School” (APTN, 2023).

{1} Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), 3.

{2} It bears noting that, as Métis researcher Max Liboiron puts it, “cultural genocide is genocide. It’s not genocide-lite.” Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Duke University Press, 2021), 107n103.

{3} See Calls to Action 71–76.

{4} Kisha Supernant, “Reconciling the Past for the Future: The Next 50 Years of Canadian Archaeology in the Post-TRC Era,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 42, no. 1 (2018): 149.

{5} For example, consult the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s National Student Memorial Register: https://nctr.ca/memorial/.

{6} For example, see Reid Gerbrandt and Sean Carleton, Debunking the “Mass Grave Hoax”: A Report on Media Coverage and Residential School Denialism in Canada (University of Manitoba Centre for Human Rights Research, 2023).

{7} For example, see Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

{8} For an expanded discussion, see Kisha Supernant and Gary Warrick, “Challenges to Critical Community-Based Archaeological Practice in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 38, no. 2 (2014): 563–91.

{9} As Max Liboiron reflects, “Community-based research . . . requires ethics that can cause loss, rather than only gain, for researchers.” Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism, 145.

{10} See Kisha Supernant et al., eds., Archaeologies of the Heart (Springer Nature, 2020).

{11} On the costs of emphasizing trauma, see Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (October 6, 2009): 409–28.