On The Collection: Ways of Seeing African American Moving Images

Rhea L. Combs

In approximately 1,000 words, we invite you to confront a work of visual media (film, photograph, painting, or object) in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture (1950 – present) and reflect upon a public or private future that the maker(s) of that piece envision, have envisioned, or a future that might be imagined through your engagement with the piece.

Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, photographs, and electrotypes, good and bad, now adorn or disfigure our dwellings … Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them. What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all.{1}

—Frederick Douglass

The Smithsonian Institution opened its 19th museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), in Washington, D.C. on September 24, 2016—nearly a century after politicians, veterans, and everyday citizens began advocating for its establishment. While the bipartisan Act of Congress established the museum in 2006, that was it. There was no location nor was there a collection. The museum’s founding director, Lonnie Bunch, and its curators, however, were committed to telling “unvarnished truths,” as historian John Hope Franklin espoused. One way we have honored this commitment is through the discovery and recovery of moving images made by African Americans, about African American experiences. Concerted efforts to catalogue and preserve documentaries, home movies, and other time-based media works have made film and video by and about African Americans a significant part of the museum’s growing collection, ensuring that historically overlooked works are placed within the pantheon of critical media studies.

The power of the camera to create a new way of seeing society and its citizens was something American statesman Frederick Douglass wrote about in the late 1800s. It is in this vein, approximately 150 years after Douglass’s comments, the museum has made lens-based media part of its collecting priority. NMAAHC’s permanent collection includes over 37,000 objects. More than 1,500 of those items are film, video, and audio recordings. Materials range in date, format, topic, and subject. The collection includes a trove of materials donated by archivist and film collector Pearl Bowser, for example. There are also films by documentary filmmaker St. Clair Bourne, such as Let the Church Say Amen! (1973); selections from NET’s award-winning television series Black Journal (1968 – 1970), produced by William Greaves; and Madeline Anderson’s groundbreaking Integration Report 1 (1960), to name just a few. A particularly special highlight of the collection are nine reels of film by minister, entrepreneur, and amateur documentarian, Solomon Sir Jones.

Presenting images of everyday life throughout Oklahoma from 1924–1928, the reels reveal thriving, socially and economically vibrant communities three years after the horrific Tulsa race riots ripped through the city’s Greenwood business district in 1921.

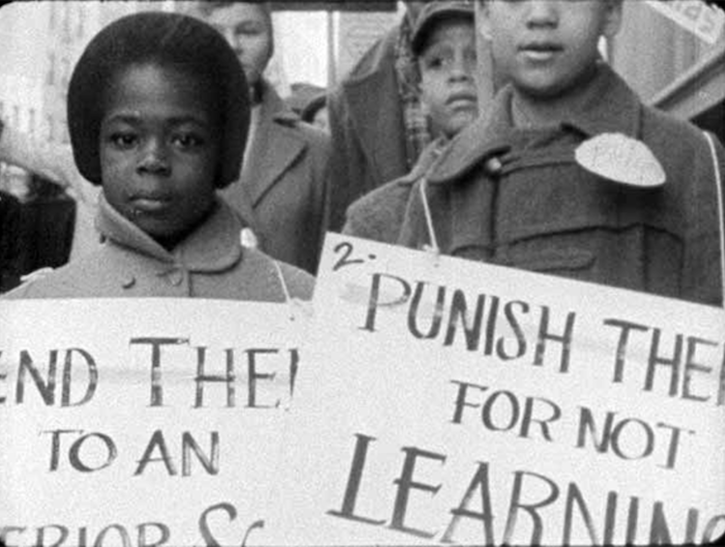

figure 1. INTEGRATION REPORT 1 (Anderson, USA, 1960).

figure 1. INTEGRATION REPORT 1 (Anderson, USA, 1960).

As a curator of film and photography, it is important to make work like polymath Lebert Sandy Bethune’s Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom (1964) accessible to scholars, filmmakers, and artists. Creating exhibitions that focus on the history of Black cinema, developing programs that offer media makers access to the moving image archives of artists and scholars, and producing public screening opportunities promotes richer discussions around larger socio-cultural topics like, race, global politics, and civil rights.

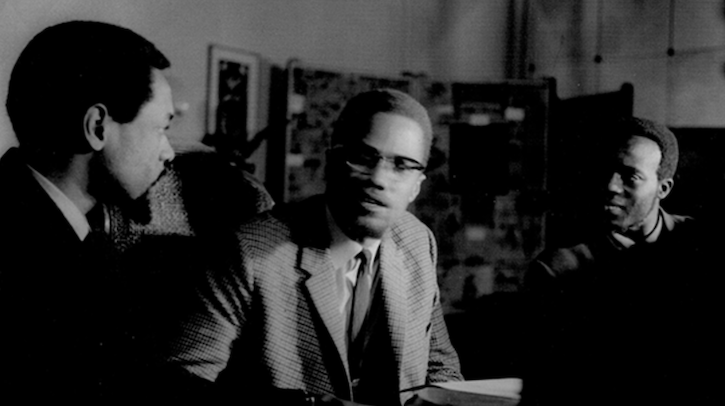

Three films directed by Bethune—Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom, Jojolo (1966), and an unfinished Pan Africa project—became a part of the museum’s permanent collection in 2018. Bethune, an unassuming man born in Kingston, Jamaica, emigrated to New York with his parents in the 1950s. An accomplished writer, poet, political activist, and protégé of Marxist and Pan-Africanist scholar C.L.R. James, Bethune also served as the assistant to artist and writer Langston Hughes for a brief period. Inspired by artist-activists like Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and others, Bethune moved to Paris in the 1960s and trained at the University of Paris. During his time there, he received a special assignment to be a guide for Malcolm X. As Bethune has explained, it was “quite by chance” that he invited Malcolm to speak to a group of students from the African diaspora. Bethune recorded the conversation and narrated the film. The film’s co-director is photographer John Taylor. It opens with a montage of Taylor’s photographs and newsreel footage depicting international struggles for people of African descent. Made in 1964, three months prior to Malcolm’s death, Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom shows the leader at a time when many of his ideas about race and politics were expanding outward toward a more global and inclusive perspective. This twenty-two-minute film contains some of the last interview footage of him prior to his death.

figure 2. MALCOLM X: STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM (Bethune and Taylor, USA, 1964).

figure 2. MALCOLM X: STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM (Bethune and Taylor, USA, 1964).

It was critical to make Bethune’s work accessible to the public at the National Museum of African American History and Culture because his portrait of Malcolm X sends historical reverberations forward. Viewers bear witness to a leader during a critical period of personal, political, and historical transition and the film provides a basis from which to expand and complicate popular knowledge and awareness that surrounds this significant figure.

Preserving and collecting works like these, supports the priority of protecting overlooked histories from falling further into obscurity. It also shows how images of African Americans in documentary film, particularly works made by African Americans, often deviate substantially from the flat, one-dimensional images that proliferated by many of the ethnographic and anthropological travelogues of previous eras (the relationship between subject and maker is not to be underestimated). The museum’s diverse collection of nontheatrical, time-based media reveals intimate, nuanced portraits of Black life and asserts ways of seeing that honor Douglass’s arguments a century and a half ago.

Title Video: “Tribute to Malcolm X,” Black Journal Segment (Anderson, 1969). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Pearl Bowser.

{1} Quoted in Laura Weyler, “A More Perfect Likeness: Frederick Douglass and the Image of the Nation, ” in Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 21.