Ways of Organizing: Institutional Forms

Aily Nash

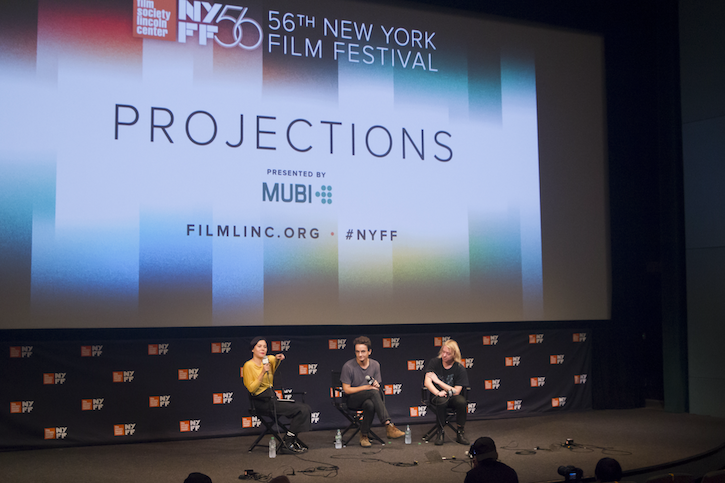

The question of the audience and engagement is a particularly difficult one that I’m continuously grappling with. It’s an area of my work that I find unsatisfactory, and one that I’m trying to find ways to improve upon. At many institutions I’ve worked with, I feel that the development of audiences is often an afterthought. I don’t work full-time at an institution, and coming in to execute a specific program, it can be challenging to make broader changes to how the program is situated within the festival or institution. For example, at the New York Film Festival (NYFF), where I co-curate “Projections,” I would love for there to be expanded programming beyond the cinema through collaborating with other spaces and organizations throughout the city to co-present moving image installations, performances, or other discursive or educational events. But this isn’t possible since “Projections” is situated within the festival as a sidebar, and there isn’t support from the institution to expand the program to include such things.

Of course programming certain artists or works brings out specific viewers, and this is a consideration when balancing programs and series. For example, with “Projections,” we strive to expand the conversation across traditions by bringing together works that straddle different worlds, formally and aesthetically cross-pollinating through interdisciplinarity. Yet the expansion of the venue or festival’s general audience is somehow seen as beyond the scope of programming. It is a task that is fragmented into distinct departments—perhaps unnecessarily and counter-productively so. In most institutions, it is the specific work of the public relations, marketing, and/or education departments, yet these conversations, goals, and approaches often feel siloed. It becomes difficult to maintain a through line between the content of the work and its potential audience. Channels for outreach have become rote and niche. It doesn’t go much beyond pitching to get written up in the appropriate outlets and sharing links on social media to followers. But how can we reach beyond our preexisting audience? How do we expand our viewership, and as a result, the conversation? Yes, programmers are in charge of the content, yet often, the institution sets the framework and possibilities for the context. Developing audiences shouldn’t only mean striving to sell out the cinema. Yet institutions often measure success in ticket sales, and consideration rarely goes into the makeup of the audience. Smaller organizations have much more flexibility and can approach their audience development more holistically. At the Images Festival in Toronto this year, we worked with many small organizations (not necessarily film or art related ones) to co-present films and programs so as to reach viewers within other disciplines and interest groups.

photo courtesy of Lindsey Seide.

photo courtesy of Lindsey Seide.

I really want to show movies to, and have discussions with, a broader viewership, but I’m still figuring out how. This isn’t about quantity versus quality—engagement should take various forms. The one-way relationship that structures many festivals—in which filmmakers are treated as the sole authority on their work—typically works against more dynamic forms of engagement. Some festivals have begun pedagogical experiments with workshops and academies, yet many of these are often focused on creating networking opportunities—a corporate “mixer” model, really—rather than it being about expanded viewership and participation.

The film seminar model, however, does succeed at achieving depth through harnessing a viewer-oriented context rather than a maker-oriented one. I’ve programmed two film seminars that were inspired by the Flaherty Seminar format: Doc’s Kingdom in Arcos de Valdevez, Portugal, and at the Tabakalera in San Sebastian, Spain. In both seminars, we saw engagement from the participants who came from a variety of backgrounds—artists, educators, political activists, writers, students, etc. We also developed an intensive program at Images Festival this past year, in the form of our Research Forum. These kinds of non-traditional pedagogical formats have always attracted me. I think it’s important that open, public engagement is not academic and is financially accessible.

Moving images have the enormous power to communicate, affect, and arouse thoughts, feelings, and actions in people. Documentary and indexical images have become so contested in today’s media climate, and it’s become all the more important for artists and viewers alike to try to understand our world by asking questions about how we look at and read images. The presentation of this kind of work is imperative to expand how viewers think about cinema, and what is possible through this medium. It is crucial to stimulate ideas and questions in viewers that can only be provoked by works that don’t provide answers. I’m thinking of artists like Kevin Jerome Everson, Deborah Stratman, Sky Hopinka, Lucy Raven, and James N. Kienitz Wilkins. These works breed a culture of experimentation, and of strange, new objects that we don’t yet understand—and inspires further creation. I want my work to create an occasion for different approaches, traditions, and conversations to come together, to inform and inspire each other—to create more overlaps, connections, and affinity. It is not easy to turn broader audiences on to formally challenging work, but this is why institutions need to offer more forms of engagement through conversations, seminars, forums, and make them available to students, emerging practitioners, and general audiences who may jump at accessible opportunities to discuss and think about cinema as a community.

Title Image Credit: Projections 4 at the 56th new york film festival (2018).